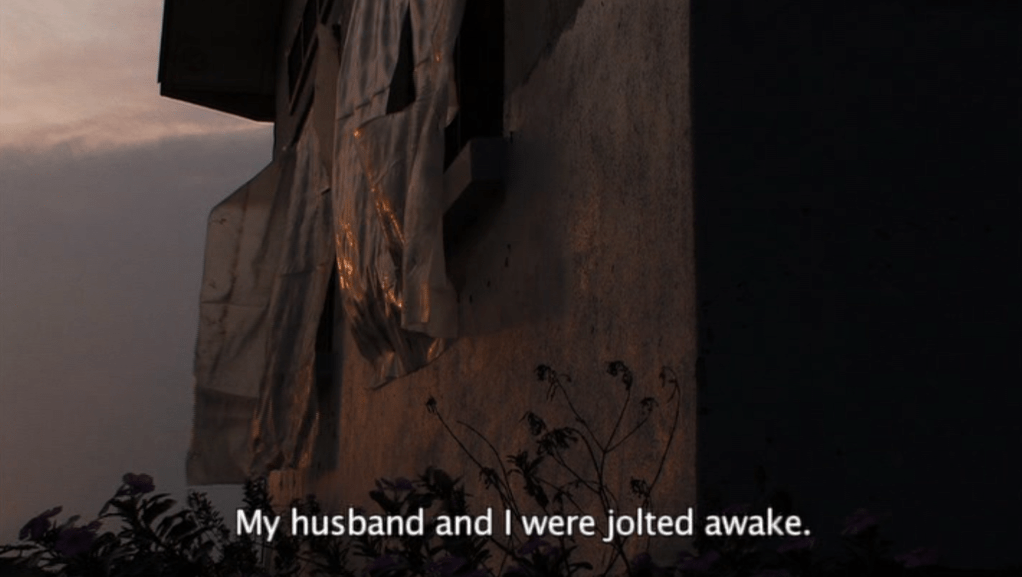

Ernst Schmidt Jr.’s Wienfilm 1896-1976 opens its subject the way a cadaver is splayed on a coroner’s table. It does not search for a beating heart but for the conditions that make Vienna both itself and something estranged from itself. Montage is now a diagnostic tool, less a method of assembling meaning than of measuring how it buckles under the weight of mortality. The filmmaker himself calls it “a collage of diverse materials aimed at conveying a distanced image of Vienna,” and this distance is the guiding principle: no seduction, no civic hagiography, only a long, unsettling look at a city that contradicts its own self-image at every turn. The result is almost two hours of historical consciousness unfurling at the pace of a slow-motion sea change.

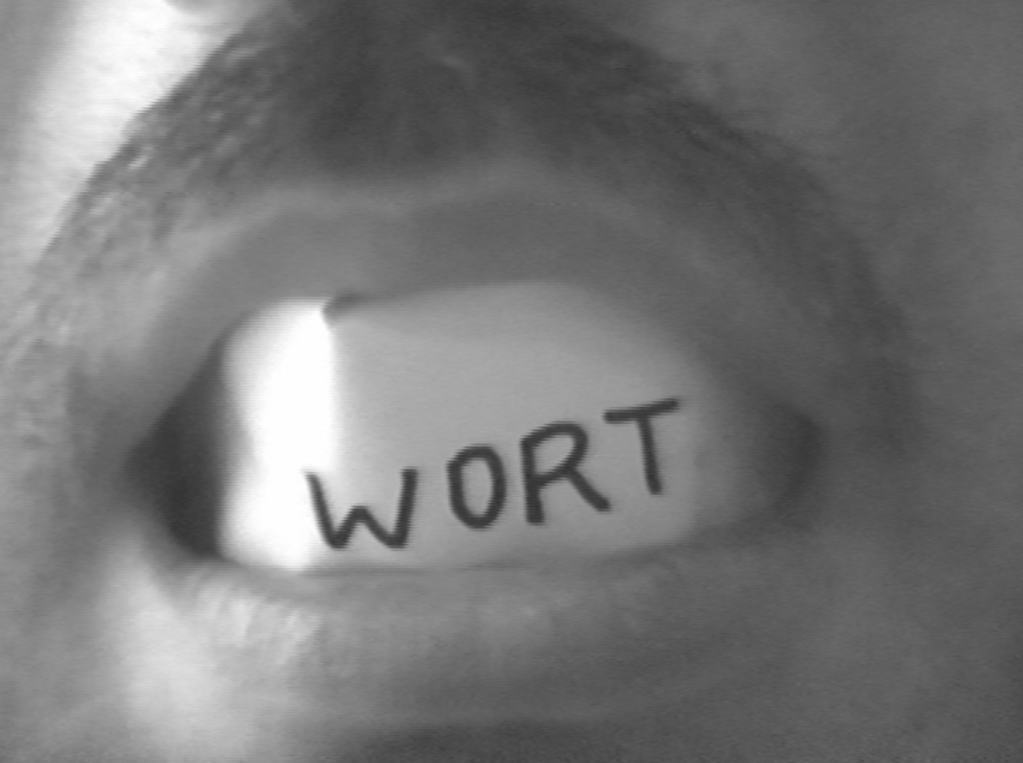

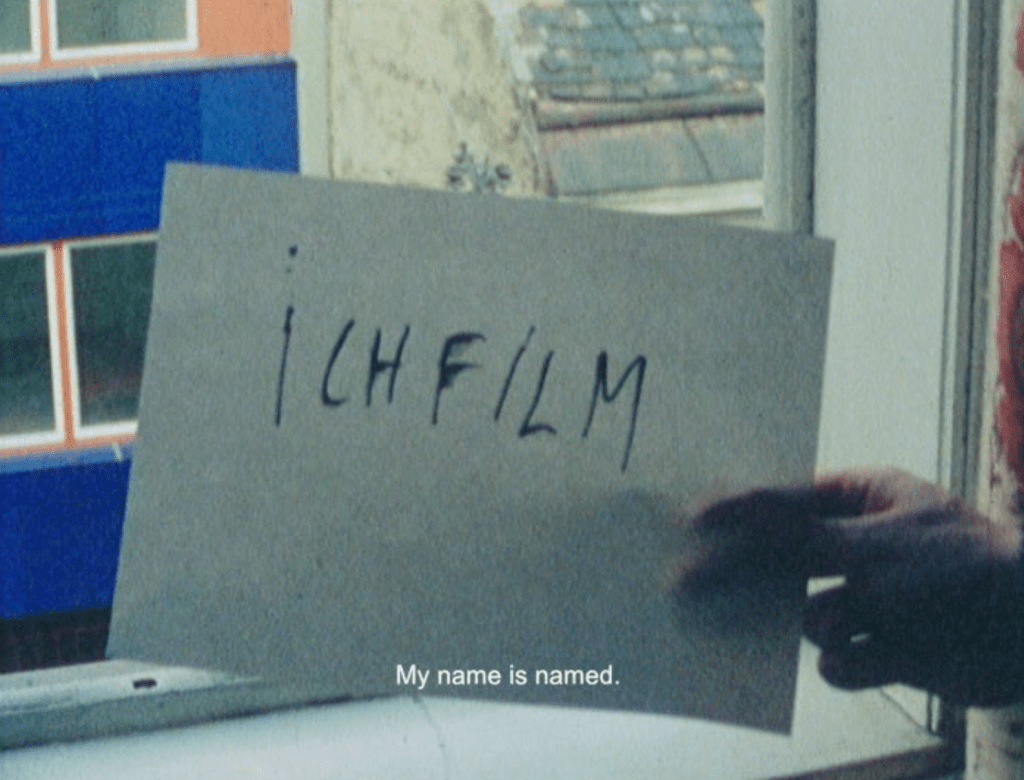

The project begins innocently enough. Two little girls draw and talk about photography, as if the film were briefly pausing to consider the act of looking before descending into its century-long excavation. Soon, Schmidt Jr. sends his camera wandering into the streets to locate the letters of his name. Thus, identity is something to be scavenged rather than inherited, pulled from signage, storefronts, and neglected typography. The artist reconstructs himself through urban residue, establishing an implicit kinship between detritus and personal (re)formation. Lumière footage from 1896 reminds us that Vienna’s filmed life began in the same mood of wonder that swept Europe. Yet here the vintage images register as a faint alarm, the first entries in an archive that will come to record both innocence and catastrophe, albeit in disproportionate amounts.

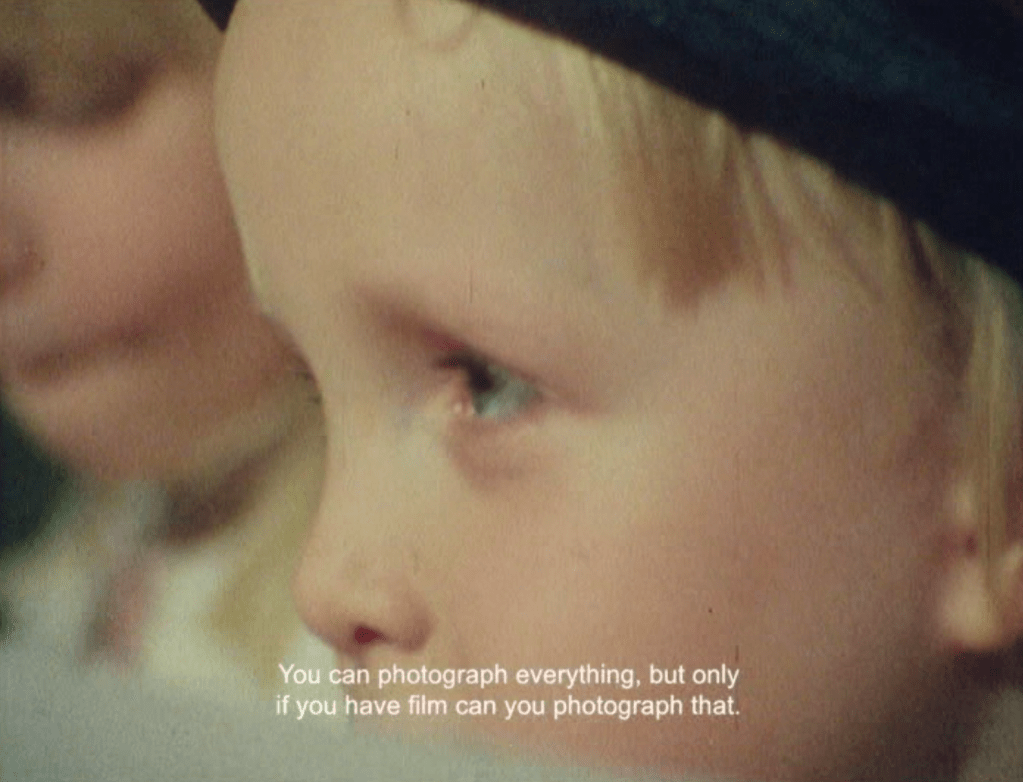

A montage of women walking follows, accompanied by a syrupy song about femininity. The sequence drifts uneasily between admiration and objectification, as if the soundtrack were trying to smooth over the very wounds it denies. And that’s when a Nazi parade cuts into frame, 1938 charging forth without commentary or warning. The simple adjacency of images does the work of showing how the bootmarks of the past can never be lifted from the present’s pavement. Peter Weibel appears interviewing passersby about who “owns” Vienna, a question that exposes civic pride as well as civic vacancy. Abandoned buildings and shuttered shops stand as ruins. Joe Berger’s remark, “You can be Viennese all over the world…just not in Vienna,” functions as a darkly comic proposition about belonging, exile, and the contradictory nature of borders.

When Chaplin arrives, mass adoration floods the screen. The crowds reveal a collective fervor that cinema alone seems able to provoke. Ecstatic public unity collides with the kitschy cheer of Wienerlieder, whose supposed affection grows sinister when paired with footage of marching columns, rubble, or muted political assemblies. Such sentimentality takes on a narcotic charge, a way of drowning out the psychic noise of its unresolved history. Freud drifts through as a spectral reference, less a person than a reminder that Vienna’s self-knowledge has always been bound to its neuroses. Dogmatic speeches rise and fall, promising clarity yet delivering only the musical rest of rhetoric. Actionists erupt briefly, warping from within. Ordinary people cross streets, ride trams, and enter buildings, each carrying a share of a saga that exceeds them.

As Wienfilm 1896-1976 nears its end, it no longer behaves like a documentary. It becomes a séance of stone. Schmidt Jr. summons imperial afterimages, post-war silences, and self-mythologizing refrains, letting their intercourse give way to an apparition built from incompatible truths. What remains is a portrait assembled from fragments that resist composition, vibrating with the discomfort of witnessing too much yet understanding too little. A city is not something to be summarized but confronted, piece by tactile piece, in all of its charm and violence, until a composite sketch is revealed that no one can fully bear to recognize as their own.