Johann Sebastian Bach

Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis

Heinz Holliger oboe

Erich Höbarth violin, direction

Camerata Bern

Recorded December 20-22, 2010

Radiostudio Zürich

Engineer: Andreas Werner

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Of

a tree, of one.

Yes, of it too. And of the woods around it. Of the woods

Untrodden, of the

thought they grew from, as sound

and half-sound and changed sound and terminal sound…

–Paul Celan, “And with the Book from Tarussa” (trans. Pierre Joris)

On October 4th, within an hour of having listened to this album for the first time, I went out for lunch, when I noticed a peculiar sight. There, sitting at an outdoor table, was a hermetic figure with a Monarch butterfly resting on his outstretched hand. How could I not engage him in a conversation? The man, I soon found out, was Rolfe Sokol, a local fixture in Ithaca, New York for over a decade and one of the most sought-after violin teachers in the area. Rolfe had saved the injured butterfly after spotting her on the side of the road. During her recovery from two crimped legs and a damaged wing, she hardly left him. As Rolfe animatedly informed me, drawing his story as he might a bow, the butterfly spent most of her time on his shoulder or perched on a finger, living off the sugar water he provided. When she had recovered enough to make short flights, he took her to the park, where she greeted strangers but always returned.

Rolfe and I inevitably turned to topics musical. After being regaled with stories of some of my favorite violinists and composers, I asked if he was familiar with ECM Records and with Heinz Holliger’s latest Bach recording. Though the answer was no on both counts, he did tell me how the butterfly reacted most positively, fluttering her wings and “stamping” her forelegs, whenever he or his students played Bach. Upon hearing this, I immediately asked for Rolfe’s address and later sent him a copy of Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis to aid in the butterfly’s recovery, for the title—which translates to “I had much affliction”—seemed appropriate for one in a stage of healing. It is in that spirit of rejuvenation that I discuss the music at hand.

Rolfe’s butterfly

Rolfe’s butterfly

With his usual blend of humility and cogency, Holliger gives us in his liner notes an informed account of these recordings, which together represent a pastiche of reconstructions, arrangements, and restorations from, to recapitulate his quoting of Hegel, the “fury of disappearance” that so befell much of Bach’s oboe literature. Such unrecoverable shadows will have cast themselves over many a Baroque enthusiast and so bear no redrawing here. In any case, after listening to this recording almost once per day since receiving it so kindly from a faraway friend, I have become as intrigued by where its beauties are going as by where they came from.

Holliger’s latest for ECM is so rich it’s almost unhealthy. Three sinfonia introductions, two from among Bach’s cantatas and one from an Easter Oratorio, form its crux. Some music simply stills us, and the darkening swells of “Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis” (BWV 21) constitute such music. Holliger and violinist Erich Höbarth intertwine like birds in slow motion, each leaving a trail of something forgotten, blazing across the sky in a slow-moving fire, by which only one’s fate can be written, ever out of reach but always readable in the light of divine countenance. But where my description may be overblown, Holliger’s technique never is, always held in check by a profound reserve that allows the music to flourish on its own terms. Bach’s mournful reflection sings with a palpable retrograde, and from its first draw pulls the center of our being toward that of some unnamable other.

Of the four concertos offered here, the c-minor for oboe, violin, strings and basso continuo (BWV 1060) is the most humbling. Joined front-stage by the nimble fingerwork of Höbarth, Holliger details a multivalent sound palette. And in the d-minor (BMV 1059) his legato phrasings explore parts of the surrounding orchestral architecture that most oboists would neglect to see, let alone articulate. The slow, waltz-like quality of the Adagio is an especially profound wind-up for the heavenward lob of the Presto that concludes. Holliger looks even more inwardly in the A-major concerto (BWV 1055). Here, he luxuriates in the subtle turns of phrase and moments of tension that seem to stretch between orchestra and soloist and dance across water with every trill. And then there is Bach’s reworking of an Alessandro Marcello concerto, which glistens with poised ornamentations. A lively dance in the Presto percolates with bewitching charm as Holliger populates every interstice with his inextinguishable passion.

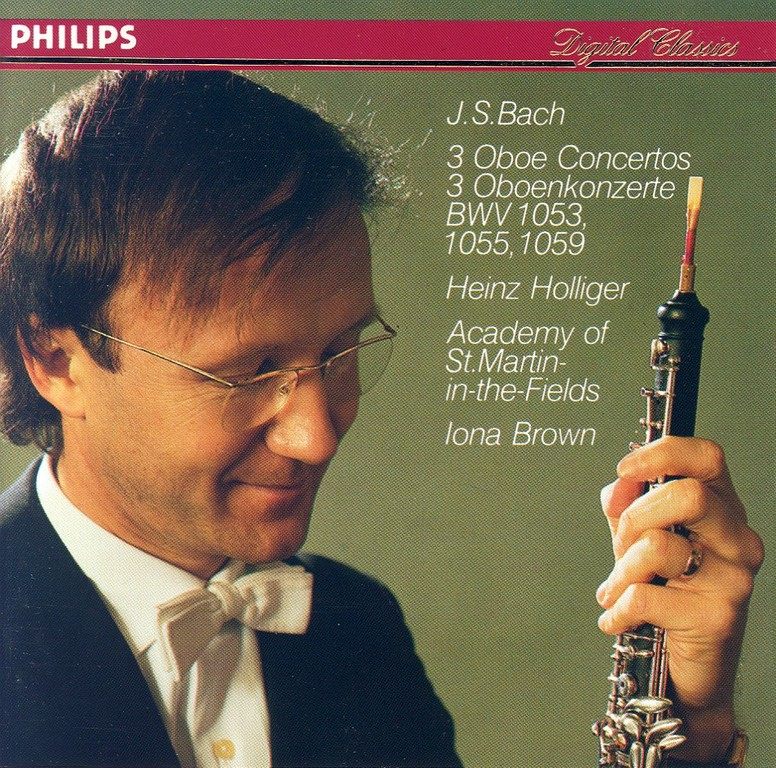

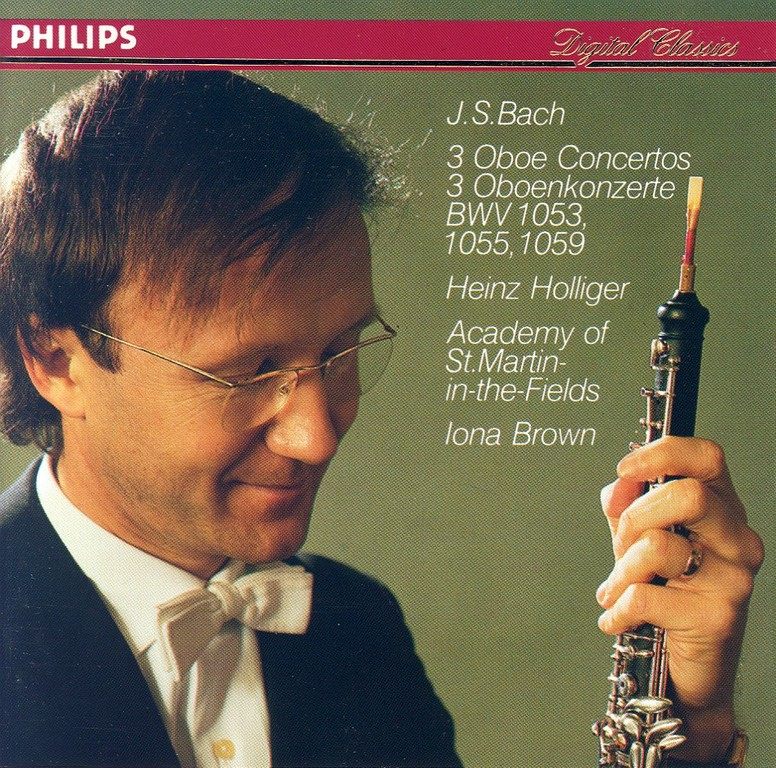

As one who believes the assembled performers to be a virtually uncriticizable combination, I risk redundancy in praising their results as a scintillating tour de force of tempo, timbre, and above all vocality. In light of the already wondrous 1982 recordings of BMV 1055 and 1059 on Philips with the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields (back during the latter’s hyphenated golden age), this could never be anything less than superlative in its complementary light.

Yet one notices also the striking differences between the two. ECM’s recording, while bright, explores this music’s deeper colors, balancing the swirls of refinished wood with an expertly miked continuo. Holliger’s playing has rarely sounded so earthy, so focused on its ephemeral task. These are not reimaginings but reawakenings. And while tempted, I hesitate to use the term “benchmark recording,” as it would speak of its interpretive possibilities as having been branded in time, checked off on the never-ending tick sheet of Bach recordings.

It is also tempting, following Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich, to think that “all roads lead back to Bach.” Yet rather than see Bach as the endpoint to a musical funnel that cuts across histories and geographies, we might better witness the avatar of a composer whose gestures of humility brought to fruition a sense of openness. We do well to resist painting Bach as a Universalist. In search of a alternate analogy, I return to the butterfly. Monarchs are known for their annual 2500-mile migration. Contrary to popular belief, no single pair of wings survives the entire journey. In essence, the group is a kaleidoscope of constant regeneration that returns a different entity from when it left. Like those roving splashes of black and burnt orange, Bach’s music itself travels in a constant state of regeneration, such that every fresh performance, every pair of ears newly enchanted, spreads its own venation of appreciation.

Two weeks ago I ran into Rolfe for the first time since our initial meeting, only to discover that his lepidopteran companion had not survived the cooling Ithaca climate in time to hear this album, but that when he received it he did play it for her. And so, in the interest of continuing this chain of memorial, which began with the death of Bach’s favored pupil (fresh in the composer’s mind when penning the titular sinfonia) and which is linked by Holliger’s loving dedications to the memories of his brother, Eric, and friend Gabriel Bürgin, if you ever find yourself in possession of this jewel of an album I hope you might also take a moment to remember Rolfe’s butterfly, who I like to imagine now rests contentedly on Bach’s shoulder, her proboscis no longer necessary for the music of the spheres that will forever sustain her.