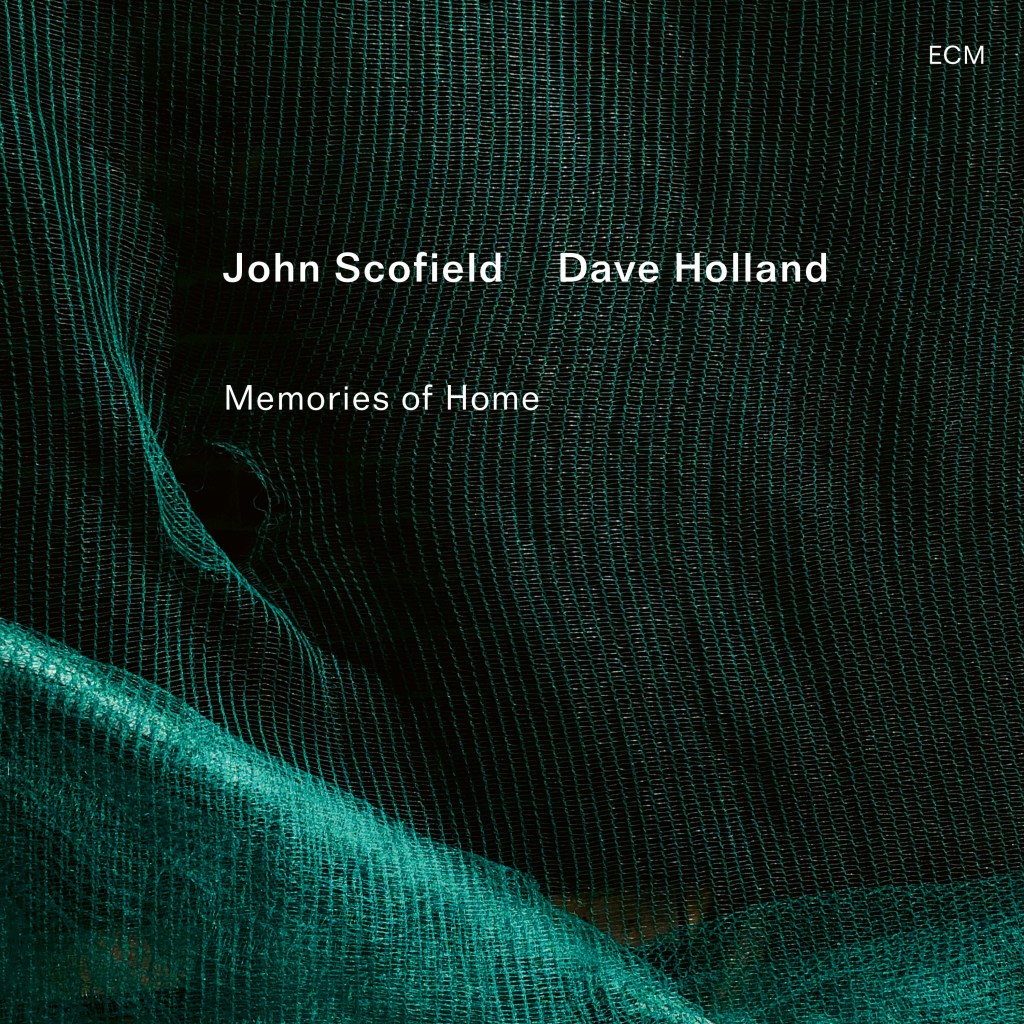

John Scofield

Dave Holland

Memories of Home

John Scofield guitar

Dave Holland double bass

Recorded August 2024 at NRS Recording Studio, Catskill NY

Engineer: Scott Petito

Cover photo: Juan Hitters

Produced by Dave Holland and John Scofield

Release date: November 21, 2025

Guitarist John Scofield and bassist Dave Holland, two musicians with such distinct sonic identities, join forces for a duo album that is as mighty as it is intimate. Despite having crossed paths countless times over the decades, whether onstage with giants like Herbie Hancock and Joe Henderson or in high-octane settings like ScoLoHoFo, Memories of Home marks their first album as a duo.

The idea had lingered for years, even surviving a pandemic-scrapped tour in 2020. When they finally hit the road in late 2021, the chemistry was immediate. By the time they toured again in 2024, making a record felt inevitable. The result mirrors their live sets with its blend of new and revisited originals shaped by decades of shared musical language. Their overlap in taste and technique makes the pairing feel natural, while their differences keep the music alive, alert, and constantly evolving.

A major point of connection, of course, is Miles Davis. Scofield’s mid-80s stint and Holland’s late-60s tenure offer a rare shared lineage, and you hear echoes of that history right away in the opener, “Icons at the Fair.” Built from the chord movement of Herbie Hancock’s version of “Scarborough Fair” (a session both musicians played on), the tune’s wistful intro quickly settles into a buoyant groove. Scofield’s rounded tone is an elegant vehicle for his improvisational flights, and the two musicians trade roles like seasoned copilots, each taking the lead before easing back into support. Holland’s solo radiates that trademark close-eyed smile, matching Scofield’s buoyancy beat for beat.

Scofield revisits several of his own classics here, each transformed by the duo format. “Meant to Be” adopts a darker hue than its earlier incarnations, its fluid changes and easy-living feel revealing two players fully at ease with themselves and each other. Holland pulls his solo seamlessly from the texture, almost as if it had been hiding there the whole time. Later, “Mine Are Blues” brings their full energies to the forefront. The drive is infectious, with the pair finishing each other’s phrases in a display of rhythmic and melodic telepathy. Scofield’s crunchy, tactile tone is on point. “Memorette,” swankier and more rhythmically playful, finds a lovely twang in the guitar and Holland sounding lush and resonant beneath it all.

Holland contributes several reimagined pieces from earlier in his career. “Mr. B,” his tribute to Ray Brown, brings out a delicate, cerebral side of Scofield, who responds to Holland’s writing with gorgeous restraint and curiosity. “Not for Nothin’,” first heard on Holland’s 2001 quintet album of the same name, reveals new secrets when reduced to its essentials. Here, the tune becomes lightning in a bottle—lean, open, and unexpectedly adventurous. Scofield seems newly inspired by the stripped-down setting, exploring bolder shapes and touches of abstraction.

The guitarist’s ballad “Easy for You” emerges as a quiet triumph that carries a gentle energy and a deep love for life. At over eight minutes, it gives both players space to breathe, to stretch, and to enjoy the subtleties of their wholesome interplay.

The album closes with two Holland compositions. “You I Love” is a vivacious romp, brimming with delight, while the contemplative, pastoral mood of the title track draws out the earthy, country-tinged side of Scofield’s playing. Like ending credits to a Western, it rides off slowly, tracing the silhouette of a hero dissolving into sunset. It’s both a musical farewell and a gentle summation of everything the duo shares.