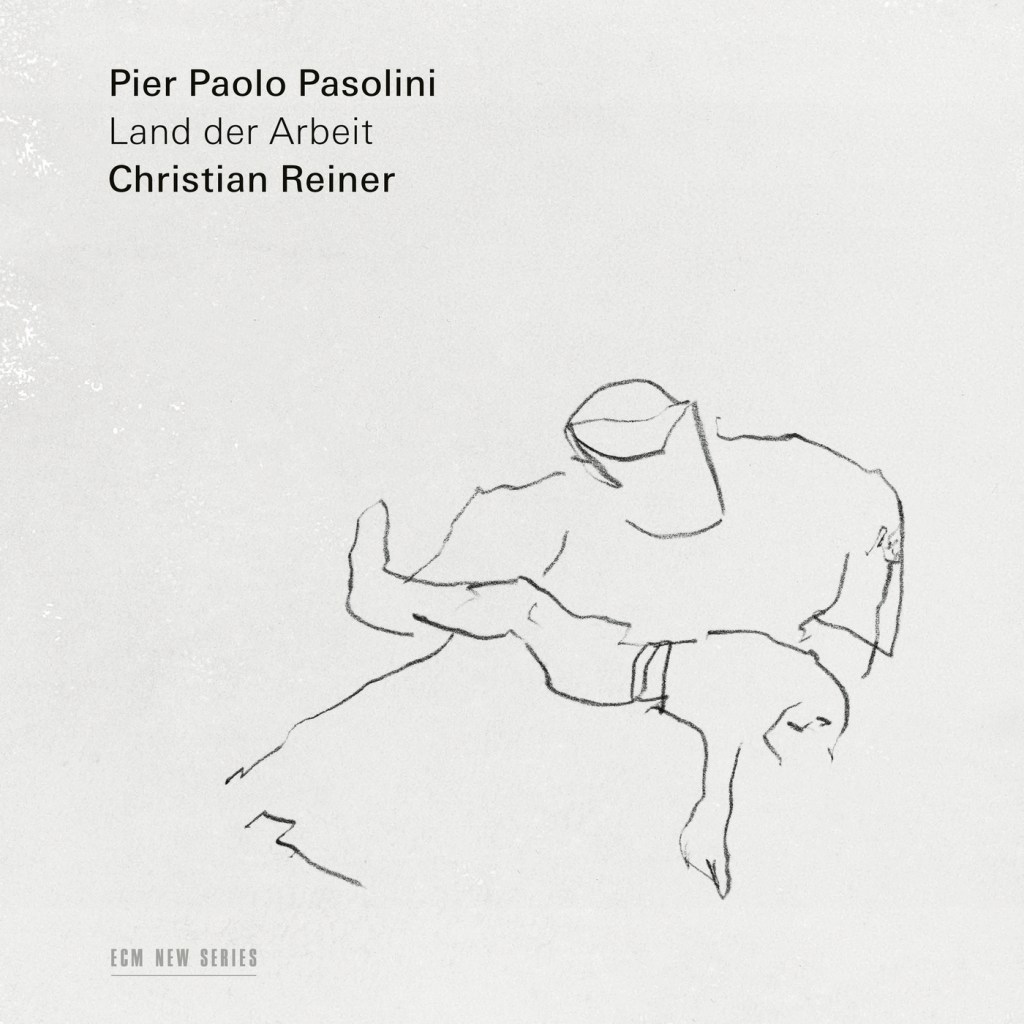

Christian Reiner

Pier Paolo Pasolini: Land der Arbeit

Christian Reiner reciter

Recorded 2021/22

Garnison7, Wien (2, 4, 5, 8)

Recording engineer: Martin Siewert

Innenhofstudios, Wien (1, 3, 6, 7)

Recording engineer: René Kornfeld

Mastering at MSM Studio, München

Engineer: Christoph Stickel

Cover drawing: Lilo Rinkens, “Arabische Pietà”

Produced by Wolf Wondratschek and Manfred Eicher

An ECM and Joint Galactical Company Production

Release date: November 18, 2022

He throws the bird in his hand into the fire,

takes the camera and films what everyone,

whether they like it or not, understands: the

animal that with its wings always ignites the

fire in which it burns.

–from “Pasolini” by Wolf Wondratschek

In 2020, the Neuberger Museum of Art at SUNY Purchase hosted an exhibition titled Pier Paolo Pasolini: Subversive Prophet. Although more widely known stateside as a filmmaker, the 20th-century (anti-)renaissance man who died in 1975 at the age of 53 was also a prolific poet, one who railed against the establishment writ large and all its material fetishes. And so, perhaps it would be more accurate to call him a prophet of subversion who treated written words much like characters in his cinema: namely, as ciphers for human sin.

The present album, a collaboration between poet Wolf Wondratschek, producer Manfred Eicher, and actor Christian Reiner, builds on previous ECM New Series releases featuring the works of Joseph Brodsky and Friedrich Hölderlin with equal acuity. In this instance, the trio zooms in on some of Pasolini’s most scathing sociopolitical insights in celebration of the 100th anniversary of his birth year. But as Wondratschek writes in his accompanying liner notes, Pasolini was someone who reveled in every band of the spectrum: “He wanted to celebrate the festival of life, the flower of passion, the flower of play, and finally, as an extreme action, the flower of death, his death.” He goes on to describe the challenges of deciding not only what to include in the span of a single compact disc but also how to bring it across verbally in a language not originally its own (all of Pasolini’s texts are read here in German translation). Thus, he wonders, “How do you go from admirer to brother of a poet?” A fair question that deserves as robust an answer as those put forth by the pasticheur of the hour.

The album’s title piece is the last stop in his collection, The Ashes of Gramsci, in which the peasants of Southern Italy toil not to live but as a means of sustaining their death. It begins innocently enough, describing the eponymous Land of Work (“Terra di Lavoro” in the original Italian) as a swath of roaming buffalo, the occasional farmhouse, and dotted crops. But as the camera zooms in on the details, a certain melancholy begins to take hold. Once humans enter the picture, we see the depravity of man come into focus:

If you look at their eyes, their hands,

a pitiful blush on their cheekbones,

where their soul, their enemy, is revealed.

Thus, the self is revealed to be one’s greatest adversary (a leitmotif in all his work, whether on page or screen). As the verses proceed, the peasants are likened to various domesticated animals, becoming increasingly less human the more they labor. The conditions are so poor that even the potential wonders of a newborn life are undermined by the observation that whatever might seem new to the young is at once tired to the old. Reiner reads with a varied cadence, at one moment flowing through the language, taking a pregnant pause the next, letting the after-effects of his speech linger in the air. The recording strips his voice of space so that it hangs from a thread of its own making.

Next is a letter written in 1963 to fellow poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko. In it, the self-styled “Catholic Marxist” attempts to bypass their intellectual aneurysms amid the broader global maelstrom to which they were both staunch intellectual observers. It’s also a tense negotiation between Pasolini’s adoration for Pope John XXIII (to whom he dedicated his film, The Gospel According to Matthew) and the looming threat of all-out nuclear war (indicated by his reference to Nikita Krushchev and the Cuban Missile Crisis).

While the title of “To the Prince” (1958) might imply a kindred slant, it’s more of an inward examination of youth’s fleeting nature, contrasted with the world’s immutability through the lens of an artist wrestling with apathy (“I am no happier, whether enjoying or suffering”). Appropriately, Reiner inflects the poem with relative brightness, holding it higher in the throat, not quite looking the listener in the eye. If it sounds lyrical at all, that may be one reason it was set to music by the band Alice in 2003.

“It’s so hard to say in a son’s words what I’m so little like in my heart.” So begins a brief yet densely packed slice of heartbreak: “Prayer to My Mother.” Written in 1962, it reveals that growing up amid unconditional love and understanding was what made him such a creature of anguish and honed his “love of bodies without souls” as a slave to time. This balance between the devotional and the deviant (his sexual proclivities on subtle yet obvious display here) is palpable.

A mysterious interlude then comes in the form of “Große Vögel, kleine Vögel” (The Hawks and the Sparrows), after Pasolini’s neorealist film of the same name from 1966. Instead of words, it draws a thread of bird song, seemingly replicated by sped-up whistling, à la Marcus Coates’s Dawn Chorus. This is followed by “When the classical world will be exhausted,” as quoted from Nico Naldini’s book, Pier Paolo Pasolini: A Life, which expresses Pasolini’s disillusionment with nature in a world destined to destroy it—a loss from which we will never recover.

All of this feels like small steps toward the giant leap of “Patmos,” a long poem from 1969 that was first published in the October/December issue of the magazine Nuovi Argomenti. The title references the island where John the Apostle was exiled and where God revealed to him what is known today as the Book of Revelation. After opening with this biblical foundation, it transitions into a list of victims of the Piazza Fontana bombing of December 12, 1969, and finally to a political analysis of then-Italian President Giuseppe Saragat. Reiner emotes with the most somber attention to detail, allowing the mood to settle on its own terms.

A poem by Wondratschek himself, “Am Quai von Siracusa” (1980), brings us to a close. With a stark insight that recalls the acuity of Paul Celan (whose works were set to music by Giya Kancheli on my favorite ECM New Series release, EXIL), it offers a bleak yet profound meditation on entropy:

The lion’s teeth are already rotten.

The cats give birth in empty palaces. And

a crack runs through the Madonna’s smile.

Thus, in these readings, we hear the fatigue of the encounter, of cycling one’s flesh through the ringer of Pasolini’s barbed words, and coming out the other side lacerated but all the more in tune with the fragility of life. Like my attempts to wade through Italian poetry by way of German on this spoken-word recording, we are forced to pick up whatever pieces we can find along the way, in the hopes of having a coherent narrative to show for it when all is said and done.