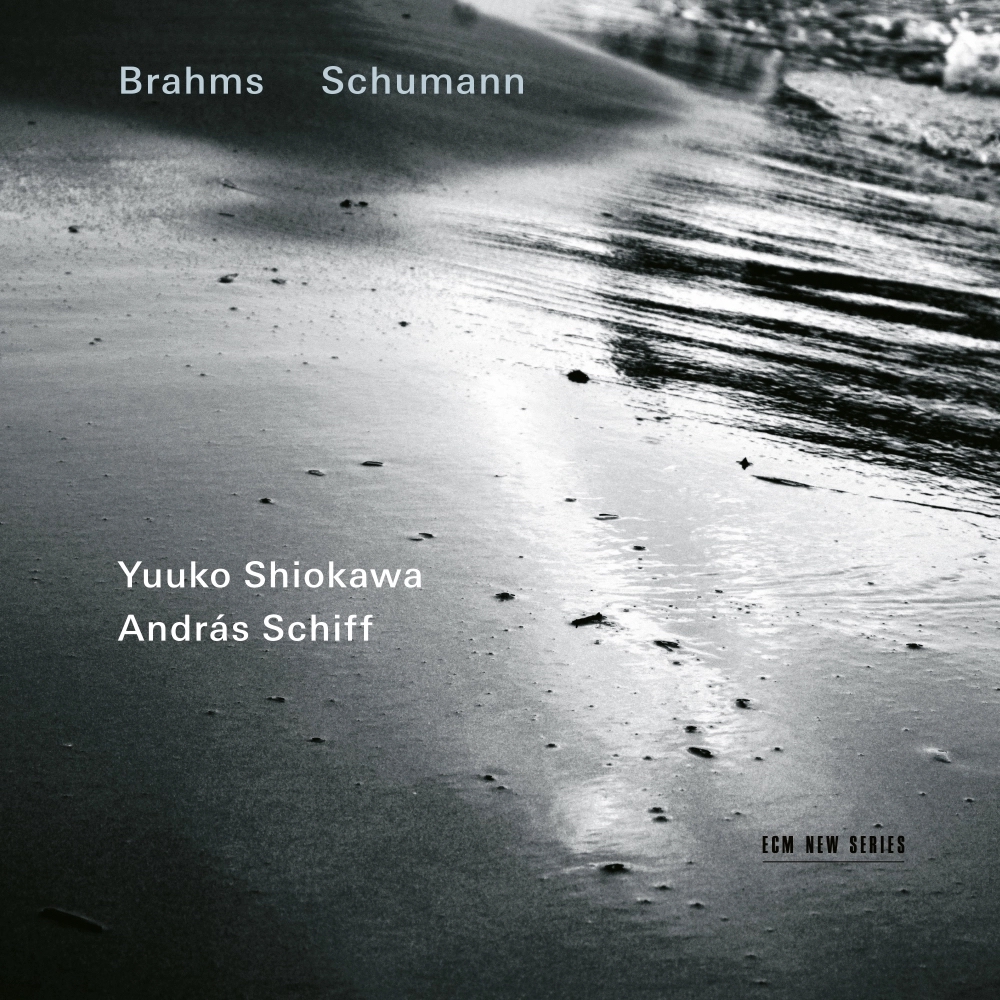

Yuuko Shiokawa

András Schiff

Brahms/Schumann

Yuuko Shiokawa violin

András Schiff piano

Recorded December 2015 (Brahms)

and January 2019 (Schumann)

Auditorio Stelio Molo RSI, Lugano

Engineer: Stephan Schellmann

Cover photo: Nadia F. Romanini

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Release date: October 11, 2024

In their second full disc for ECM New Series, violinist Yuuko Shiokawa and pianist András Schiff present two 19th-century sonatas of the highest caliber by Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) and Robert Schumann (1810-1856). The first half of the program is taken by Brahms’s Violin Sonata No. 1 in G major, op. 78. Composed in 1878, immediately after his violin concerto, it is affectionately known as the “Regenliedsonate” (Rain Sonata) for references to his two songs, “Regenlied” (Rain Song) and “Nachklang” (Lingering Sound), both gifted to Clara Schumann for her 54th birthday. We can easily share in her gratitude for finding those melodies she so cherished incorporated into a sonata of abundant riches, especially when considering that Brahms burned his early attempts at the genre. “Regenlied” opens the first and third movements, growing from the earth not as a sprout but as a fully formed tree. Like time-lapse photography, it allows us to see an entire life cycle in hindsight before we can fully grasp what is being reflected upon. Between the seamless notecraft in the violin and the piano’s dynamic underpinning, there is an orchestral sensibility at play. Despite the lively development, the outer husk is rooted in melancholy and emotional density. It whispers when it dances, shouts when it prays. The central Adagio is more funereal by contrast. As the violin works its lines from inner to outer sanctum, it never lets the wind get in the way of its grief. Meanwhile, the piano is more insistent and rouses its companion from slumber into the sharper edges of reality, leading it through every turn thereof without so much as a nick. The final stretch works through shaded pathways and hard-to-reach areas with sublime attention to detail, ending on a transcendent double stop.

Although Brahms’ great admirer Robert Schumann had never written a violin sonata, at the urging of Ferdinand David (concertmaster from the Leipzig Gewandhaus and the dedicatee of Mendelssohn’s violin concerto), he eventually relented. However, being displeased with his first attempt, he dedicated the Violin Sonata No. 2 in d minor, op. 121, to David instead. Clara and violinist Joseph Joachim gave its premiere in 1853. A massive piece in four parts, it turns the concept of “chamber music” on its head. Unlike this program’s accompanying sonata, it takes its time to mature (at 13 minutes, the opening movement alone is exactly half the length of Brahms’ entire sonata). It is also a profound litmus test of any duo’s attempts at the form, and in that respect, Schiff and Shiokawa defer to the score instead of their egos. The second movement is a soft burst of energy, giving shape to each motivic cell as if it were a brief dance to be savored before its steps are forgotten. From flowing to syncopated, we are carried through the third movement on the back of a groundswell that always keeps its shape, only enlarging and reducing before morphing into a tender staccato. The final movement is a masterclass in controlled drama that feels made for these four hands.

The sensitive playing, which gives its fullest, most heartfelt attention to every detail, is only matched by the recording. Engineer Stephan Schellmann brings a somewhat distant quality to the proceedings so as not to cloud the listener’s judgment with virtuosity. Instead, we are invited to sit in the back of the room, letting the music find us of its own volition, ready and waiting.