Another review by yours truly, this of Kayhan Kalhor and Erdal Erzincan’s recently released Kula Kulluk Yakışır Mı, is now available to read in RootsWorld online magazine. You can read my take on this masterful album here.

World Music

Anouar Brahem Trio: Astrakan café (ECM 1718)

Anouar Brahem

Astrakan café

Anouar Brahem oud

Barbaros Erköse clarinet

Lassad Hosni bendir, darbouka

Recorded June 1999, Monastery of St. Gerold, Austria

Engineer: Markus Heiland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem has singlehandedly rewritten the history of his instrument, elevating its status to self-contained orchestra. Like a film director whose camera is a third eye, he paints in moving images—no coincidence, given that much of his music is written for screen and stage. His virtuosity is the pulsing stuff of life and therein lies the power of his music, itself a language beyond the grasp of this meager orthography. Astrakan Café is among his best records, for the solemnity of its nourishment is as attuned to the ether as the two musicians who aid in Brahem’s quest to describe its taste. Turkish clarinetist Barbaros Erköse returns after his invaluable contributions to Conte de l’incroyable amour, intense as ever in the spine-tingling depth of his song. Percussionist and longtime Brahem collaborator Lassad Hosni brings likeminded expertise to the table, adding just the right dash of spice to every tune.

Of those tunes we receive a lavish tale, each chapter a depth-sounding such as only Brahem can elucidate. As a meeting place, the titular café lends itself to intimate conversations and a feeling of community across borders. It introduces us to the protagonists of an epic, cohesive narrative. Erköse’s opening gambit in “Aube rouge à Grozny” cuts straight to the marrow, his notes captured at the height of their emotional density. If this is the defining of a door, the title track is the opening of it. Brahem’s plectrum takes its first dance steps into the morning, the streets fresh with vendor smoke and tourist chatter. Beyond them is “The Mozdok’s Train,” in which the trio comes together in the spirit of travel, not as outsiders but as those whose home is wherever they happen to be: disciples to no one but the steps they have yet to take. Brahem chooses his words carefully. He rallies heroes and villains, spirits and the lowly, in a single breath and submits them to his verbal employ. Little do the passengers know that in the next car over, wedged between a folded shirt and a thumb-printed map, is a box of “Blue Jewels.” Brahem sets the stage as Erköse inlays the clasp that keeps those secrets locked. Hosni jacks up the train’s speed. His are the fingers drumming on the stretched leather of a many-stickered suitcase, the conductor’s practiced hand on burnished controls. A memory assails this assailant, a vision of love long buried until now. It awakens in him the will to change in “Nihawend Lunga,” which moves at a clip so untouchable that its eyes bleed silk, a spider’s web for the prey of “Ashkabad.” Erköse flings cries backward and sideways, writhing in the vision of a life he could have had. And just before the train drowns in the darkness of a tunnel, he jumps from an open door and into the mirage of “Halfaouine.” He awakens to the themes of a passing caravan and clutches his prize even as the “Parfum de Gitane” seeks him out like a desert oasis. He listens to the elder sharing tales in “Khotan,” a solo track from Brahem. Youth returns in “Karakoum” as if time has reversed. This lifts his spirit to the realm of “Astara.” Here feet tread lightly but surely, using mountains as stepping-stones to walk across distant suns. Erköse’s haunting monologue, rendered in hourglass shape, inspires a measured line of flight through the alleys of “Dar es Salaam,” across the waters of “Hija pechref,” and back to the album’s title scene, sipping at the bitter fruits of the earth until these fantasies become apparent to us, ephemeral like the swirl of cream that pales into sepia drink.

<< Heinz Holliger: Schneewittchen (ECM 1715/16 NS)

>> Mat Maneri: Trinity (ECM 1719)

Anouar Brahem: The Astounding Eyes Of Rita (ECM 2075)

Anouar Brahem

The Astounding Eyes Of Rita

Anouar Brahem oud

Klaus Gesing bass clarinet

Björn Meyer bass

Khaled Yassine darbouka, bendir

Recorded October 2008 at Artesuono Studio, Udine

Engineer: Stefano Amerio

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Between Rita and my eyes

There is a rifle

And whoever knows Rita

Kneels and prays

To the divinity in those honey-colored eyes

–Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008)

Anouar Brahem’s The Astounding Eyes Of Rita belongs right next to Tomasz Stanko’s Dark Eyes in that sparsely populated category of great ocular titles. Its blend of oud, bass clarinet, bass guitar, and hand drums nests firmly in an outer skin that welcomes all hemispheres into its audible signature. As one of the world’s greatest living masters of the oud, Brahem has thoroughly absorbed its many lives and draws upon them at a plectrum’s touch. Yet he has also done a phenomenal thing, revitalizing the instrument’s musical possibilities through and beyond the very traditions that inform it. Rita represents a mode of composition (all the music here is his own) that he has come to favor: namely, sitting with his oud and letting it sing to him until moved to capture on paper a glint in its endless melodic river. From such seeds he has nurtured a cohesive eight-part program that pools the talents of percussionist Khaled Yassine (playing here mainly the darbouka, or goblet drum), bass clarinetist Klaus Gesing (heard previously on Norma Winstone’s Distances), and electric bassist Björn Meyer (of Nik Bärtsch’s popular Ronin outfit): four as one, joined at the fulcrum like a card twice folded.

Meyer is an especially creative addition. His snaking incense smoke adds a touch of groove to the album’s bookends (“The Lover Of Beirut” and “For No Apparent Reason”) while also emboldening the most personal reflections (e.g., “Waking State”) with due attention and insight. He is nowhere so integrated, however, than in the engaging “Dance With Waves.” Because of him, an otherwise translucent veil thickens into full-blown tapestry, splashed with burnt sienna and vermillion. These are waves internal, drawn not on water but in blood, spoken in the signs of love.

Yassine is another revelation. He reads into every action of his fellow musicians as if it were a dance, painting his entrances carefully as light breaking cloud. Fans of Omar Faruk Tekbilek are sure to feel at home in the way percussion and oud converse throughout Rita, most notably in the title track and in the more absorbent “Al Birwa.” Gesing, for his part, airs his feathers dry in the warm air of “Galilee Mon Amour” and gilds “Stopover At Djibouti” with lilting filigree.

Brahem, however, is the sun of this particular galaxy. His exciting use of harmonics, as in “Stopover At Djibouti,” adds notable color to an already evocative style, weaving through bustling crowds even as he paints them. We can practically feel his mind working and reworking every stone beneath their feet until it offers safest passage. Inspired as much by everyday life as by the dreams that warp it, he focuses on the spaces between the strings, shaping the air that whispers through them into full-fledged texts. His plucking brings a diacritical edge to their base forms, glyphic and real.

(To hear samples of The Astounding Eyes Of Rita, click here.)

Brahem/Surman/Holland: Thimar (ECM 1641)

Anouar Brahem oud

John Surman bass clarinet and soprano saxophone

Dave Holland double-bass

Recorded March 13-15, 1997 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

The moment’s depth is greater than that of the future.

–Rabia of Basra (714-801)

Oudist Anouar Brahem brings his passion for past and future together in the present recording with reedist John Surman and bassist Dave Holland. Although he has singlehandedly revived the oud as a solo instrument, collaboration has always been at the heart of his craft, whether between himself and the spirit that moves him or with the muses of others. Most of the material on Thimar is Brahem’s and its lack of chording and bar lines in the scores presented Holland and Surman with new and fruitful challenges. One would hardly know it from the fluidity of the session. The album’s title means “fruits” in Arabic and, like those on a tree, the tunes it designates aren’t so much blended as connected by bark, water, and minerals. The press release cites recent musicological research which suggests that jazz may have its roots in the Middle East, for the West African musical traditions it mined were already syntheses of Islamic influences. This is not a “fusion” project. It is an illumination of roots.

Brahem also brings a love of Surman and Holland’s work, introduced to him by way of producer Manfred Eicher, notably through Road To Saint Ives and Angel Song. We might not be wrong, then, in shelving Thimar alongside those ECM gems. The latter of the two is especially ripe for comparison, as it likewise pushes jazz envelopes in an intimate, percussion-less setting. Only here, the added element of Brahem’s keen restraint breeds an enchantment of a different order. Despite his centrality in the program that unfolds, it is some time before he enters the stage. Instead, “Badhra” opens with an adaptive, harmonium-like drone from Holland and Surman’s buttery soprano wafting in the breeze. Holland melts into a solo that rises from the earth, soil made flesh. One might say he treats his bass like an oud, so that when Brahem appears at last it feels like a natural extension—youth to ancestor—and renders Surman’s intonation all the more calligraphic for its contours.

Surman is formidable in this setting, not by means of technical flourish but more so by the movement of his playing. He scribbles masterfully in “Mazad,” bringing an ever-deepening sense of destination to perhaps the most recognizable soprano in recorded sound. That singing reed has hardly sounded better. He further provides a lone interlude in “Waqt,” and one original, “Kernow” (Old English for “Cornwall”), in which his bass clarinet shadowdances with oud.

Holland’s contributions are equally profound. His walking lines in “Kashf” inspire a unified sermon from the trio and plunk like amplified raindrops from leaf to leaf in “Houdouth.” He is an accommodating and adaptable soul, especially in “Talwin,” where his drum-like sensibilities bring rhythmic drive (as they did in Angel Song) to the exchanges swirling around him.

For all the highs and lows, Brahem remains the ultimate truth of these proceedings, our guide on a journey he defines as he goes along. The heart-to-heart tunefulness of “Uns” pins the album’s ethos on its sleeve, evoking villages and bustling metropolises alike. In “Qurb” he adds metallic taste to Holland’s protracted Brew and sings into the tunnel. His “Al Hizam Al Dhahbi,” with its fluid doublings and harmonies, is the session’s crown, a memory in the making. There is a locomotive circuitry in his writing that runs all the way through “Hulmu Rabia” (Rabia’s Dream), signing off elegiacally with a nod to the first female mystic of Islam.

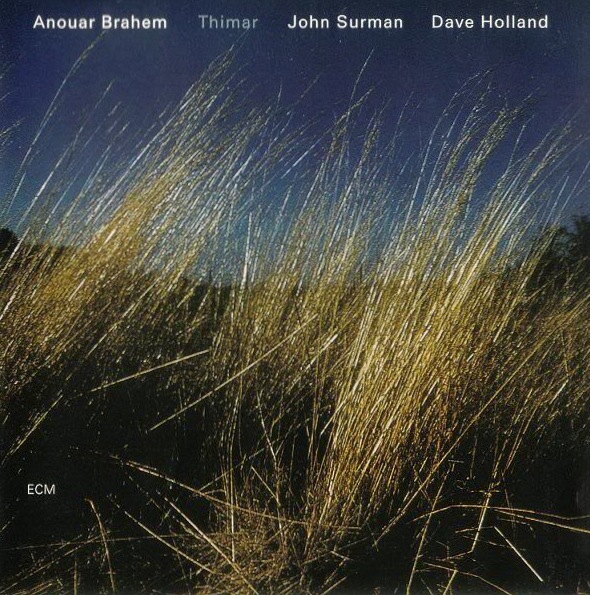

Thimar holds a coveted place in my listening life, for it was my first time hearing each of its three musicians. Separately, they are powerhouses of influence in their respective fields. Together, they are like the cover photograph: Holland the silhouetted land against Surman’s gradated sky, and Brahem the strings hatching their meeting at dusk.

<< Keith Jarrett: La Scala (ECM 1640)

>> OM: A Retrospective (ECM 1642)

Review of “The Arch” in RootsWorld

Please check out my latest review for RootsWorld online magazine regarding a phenomenal album entitled The Arch, which features Nils Petter Molvær, Bill Frisell, Ryuichi Sakamoto, Laurie Anderson, and tens of others in an unprecedented crossover project built around a core sound spun by the Eva Quartet (of the famous Le Mystere Des Voix Bulgares) and late French composer, producer, and world music dot connector Hector Zazou. You won’t want to miss this one.