Meredith Monk

Dolmen Music

Meredith Monk voice, piano

Collin Walcott percussion, violin

Steve Lockwood piano

Andrea Goodman voice

Monika Solem voice

Paul Langland voice

Robert Een voice, cello

Julius Eastman percussion, voice

Recorded March 1980 and January 1981 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher and Collin Walcott

Like much of Meredith Monk’s work, the atmospheres on this album are as foreign as they are familiar and comprise a vivid testament to the staying power of her compositional talents. When I first heard Dolmen Music as a teenager, I thought of it as folk music from lands that had yet to be discovered (admittedly, this interpretation was shaped by an oft-cited description to the same effect). Listening to it anew, I prefer to think of it as music that comes from a place so deep within, so familiar, that we tremble to hear it blatantly exposed. Monk’s music is all about the voice: it extends from the voice, begins and ends in the throat, reveling in its elasticity, its pliancy, its fragility.

Gotham Lullaby

Over a sparse layer of four-note arpeggios, Monk sings and squeals, tracing her swan song in the dust. Sustained tones hover in the background just out of reach as her voice ebbs and flows along a wordless coast. This is a lullaby of trees, if not for trees; a dream of darkness between branches and the decay of leaves falling past the city’s edge; a place where the wind can still be felt…

Travelling

This little journey springs to life with a rollicking piano laced with ritualistic drumbeats. Monk carries full weight in her confident ululations. The emergence of a rain stick adds an air of ceremony, where the piano becomes our circle and Monk the medium who channels voices of the dead in a semblance of life. Words dissolve, wetted by the trickling of monosyllables, grunts, and cries. Monk converses with her self, as if the piano were not another voice but a landscape in which the voice has found purchase. She casts her lot into the chasm at her feet as one other voice takes up the call, floating like a severed head in the ether, its mouth agape to expel the song of its birth and its death.

The Tale

A thread of piano and mouth organ supports a series of vocal beads in which we get our first and only discernible words. Over this conformist backdrop, she proclaims:

I still have my hands.

I still have my mind.

I still have my money.

I still have my telephone…hello, hellooo, hellooooo?

And between these seemingly innocuous interjections, she riddles our attention with rhythmic laughter against the sound of breaking glass, the detritus of the living.

I still have my memory.

I still have my gold ring…beautiful, I love it, I love it!

I still have my allergies.

I still have my philosophy.

This is not the voice of the insane, despite what its many disjunctions might have us believe. It is the voice of a larger social body gone awry rather than that of a single individual corrupted by its oppressive infrastructure.

Biography

This is the most emotional composition on the album and makes me stop what I’m doing every time it comes on. It is a keen in reverse that scrapes the interiors of our lungs. Peeking out from the deepest recesses of articulation, Monk sings as if in mourning. Her utter abandon allows her access to divine control through the very lack of her desire to control. In doing so, she looses the strictures of emotional conduct, shedding the outer walls of her physical makeup. She cries as she sings, intoning and droning. Her register strays into animal territory, as if intent on communicating to any and all creatures that might be listening. She runs through this vocal catalog, as it were, as a way of rearticulating the nature of her supposed loss and the comportment of its breathing remnants. This piece in particular rests on a razor’s edge, seemingly content on lying back and letting the world press down until it is cleaved in two. She wakes and walks, a divided self, into the night.

Dolmen Music

The last 24 minutes of the album are dedicated to its title piece, and what an epic journey it is. Dolmen Music unfolds liturgically, as delicate as it is persistent. A cello breathes into our ears with soft harmonics: introit. Women’s voices evoke the fundamental phonemic underpinnings of language. This language is not primitive so much as formative, spreading its vocabulary across space and time. Male voices process, lilting with “Ahs” that degenerate into a sort of ritualistic aphasia constrained only by time signatures. The cello returns: communion. The congregation partakes of a musical host and drinks vocal wine. And in the ecstatic peace that follows, Monk’s voices gather energy and speed with evangelical fervor. The voices work in canon, floating even as they crash into the limits of meaning.

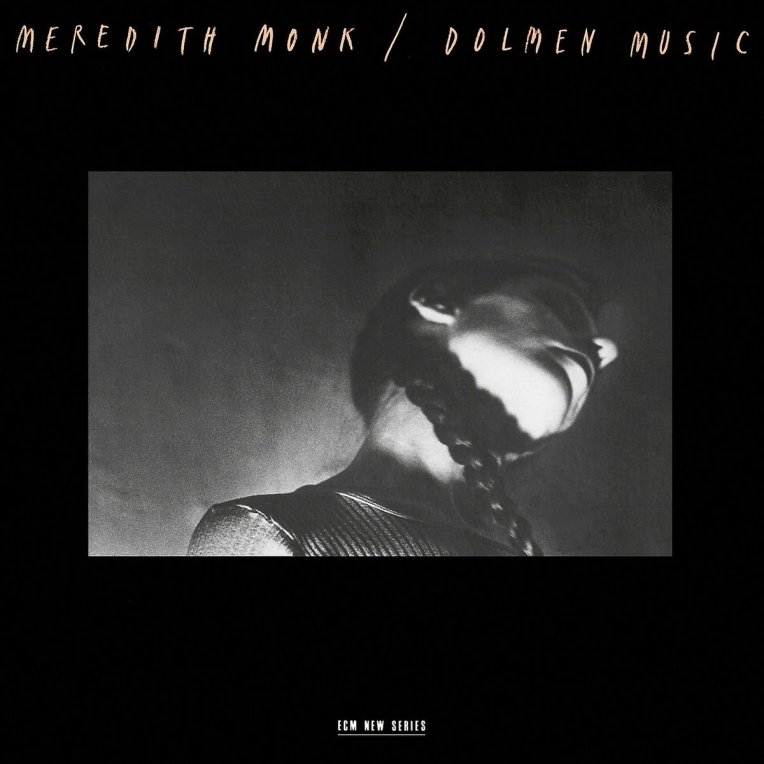

With this album Monk reinvigorated the linear song, the sole/soul singer, the monophonic performer. With the barest resources, she and her highly trained ensemble gave us an eternity of sounds. Dolmen Music makes a stunning addition to any music collection not only for its audible dimensions, but also as an art object, for it boasts one of the most perfectly suited covers in the entire ECM catalog.

<< Thomas Demenga/Heinz Reber: Cellorganics (ECM 1196 NS)

>> Steve Eliovson: Dawn Dance (ECM 1198)