“You wish to see, listen; hearing is a step towards vision.”

–Saint Bernard of Clairvaux (ca. 1090-1153)

The act of looking has long been likened to that of listening. Visual art, by no mere coincidence, is often spoken of in compositional terms, as great paintings and sculptures may be likened to symphonies in complexity and coordination. In music itself, sight reading is the quintessential form of looking as listening: The studied mind can track attention across a score and hear the music without a single musician present. But what of listening as an act of looking? Such has been the ethos of ECM Records since its inception.

Although the label has come to have a certain “look” to its admirers, it achieves in its aesthetic presentation not a look but a sound. One listens to an ECM album cover—be it a somber black-and-white photograph, an abstract painting, or a typographic assembly—by hearing it through the eyes. Although the images themselves are not necessarily reflective of the music, and only occasionally of those performing it, they do provide a framework for the disc sheathed within. As was already demonstrated in this book’s predecessor, Sleeves of Desire: A Cover Story, an ECM album is a liminal reality in which the self before and the self after find cohesion at the intersection of life and art.

In the case of ECM, it’s not the cover that necessarily provides insight into the music but, if anything, the music that provides insight into the cover. One example that comes immediately to mind is the montage that graces Pat Metheny’s New Chautauqua:

What could Dieter Rehm’s photo of the Autobahn between Zurich and Munich have to do with such a distinctly American sound? Perhaps nothing when viewed from that POV. But flip the telescope around, turning it into a microscope, and the open road now becomes a universal call to nomadism and to the magnitude of the unknown, of which Metheny’s music is a maverick flagbearer. And herein lies the attraction of the ECM-album-as-object: It invites us to step outside our skins as a way of more fully inhabiting them.

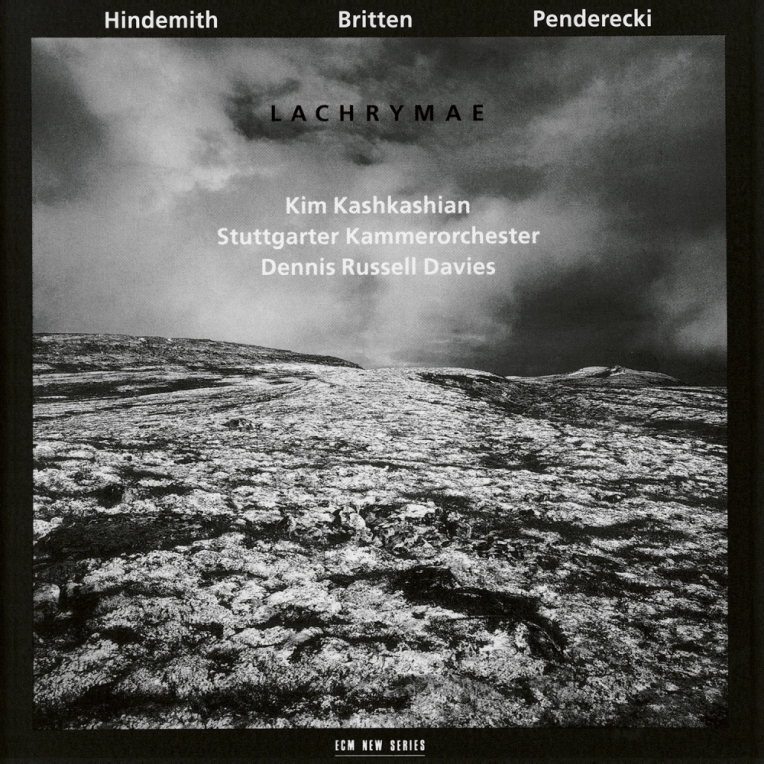

“In terms of the gaze,” writes Jean-Luc Nancy, “the subject is referred back to itself as object. In terms of listening, it is to itself that the subject refers or refers back.” It may feel natural to separate these two acts. Still, the full package of an ECM album turns closed circuits into open ones, reconnecting us with something childlike, primal if you will, by allowing us to feel that tingle of excitement every time we press PLAY and, after five seconds of anticipation, are thrown into some of the most beautiful dislocations imaginable in recorded music. As La Monte Young once put it to Tony Conrad: “Isn’t it wonderful if someone listens to something he is ordinarily supposed to look at?” Indeed, we can be sure of reuniting with that same wonder when experiencing the unusual harmony that can only be found between such a counterpoint of sound and image. For how can one behold Jim Bengston’s stark monochromatic landforms on Lachrymae and not want to traverse them with Paul Hindemith’s Trauermusik as guide?

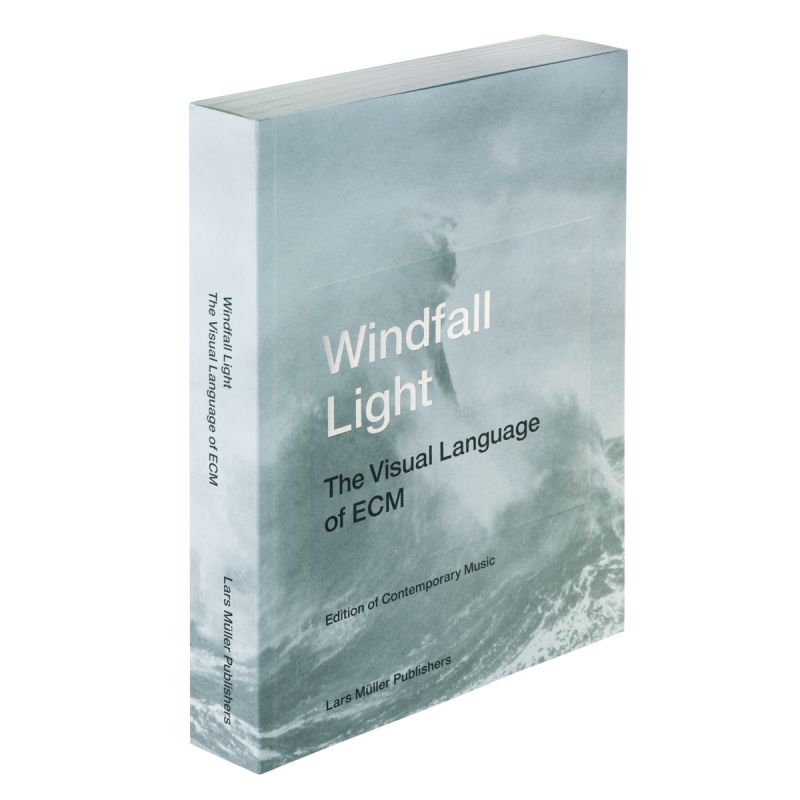

Not only is there a relationship to be found between covers and the albums they grace, but there is also much to discover in new juxtapositions. Because the images in Windfall Light are presented somewhat thematically, whether by photographer or visual motif, we are invited to explore associations we might not otherwise have made. One noteworthy spread, for example, pairs Robert Schumann: In Concert with Angel Song, thereby stimulating our curiosity for the unseen electricity between them.

Furthermore, the book contains five richly varied essays to immerse ourselves in.

In “When Twilight Comes,” German journalist Thomas Steinfeld dutifully expresses the viability of ECM’s visual identity as necessarily open-ended: “None of these pictures is an illustration in the narrow sense of the word. None of them refers to either the music or the musicians as a decoration. None of them pretends to give an interpretation or even to be interpreted on its own.” They are, rather, accompaniments. “Each is a hieroglyph,” he goes on to say, “free from much of its potential meaning, a work of dreamlike qualities, taken from nothing, a sudden objection against the profane and its often inescapable presence.” Steinfeld also notes the prevalence of water in ECM album covers—not as a reflective but a dynamic force—in addition to abstracts, street scenes, and less definable paeans to silence. Regarding the rare portraits of the actual featured musicians (Paul Motian, Meredith Monk, Keith Jarrett, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Charles Lloyd, etc.), he wonders: “Is this an accident, an honor, a matter of circumstance, or devotion?”

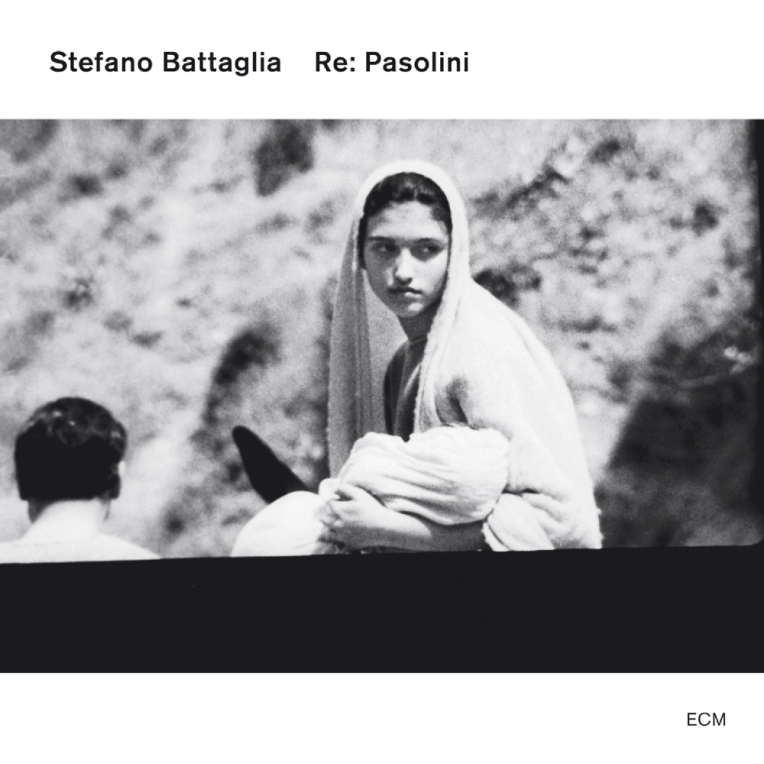

Author and museum curator Katharina Epprecht goes a step further in evoking the term “Transmedia Images.” By the title of her contribution, she means to suggest that ECM’s covers possess an interdisciplinary adjacency. Rather than being tautological loops, they are part of a “vast puzzle,” each a doorway into other senses and materialities. Thus, it is not the image’s ability to illustrate the music but rather “the immensely refined way that it handles unexpected shifts of meaning” that any listener will inevitably encounter. And while the images may be “based on correspondence to the character and quality of the music,” they are not beholden to it. Hence their potential as catalysts for personal transformation. “[T]he carefully packaged silver discs,” she waxes most literally, “are light and portable companions through life, motivating us to engage in contemplation, to pause for a moment.” In that respect, they allow us to understand more about our place in the world by questioning the many borders we draw around, through, over, and under it. Epprecht even provides a quintessential example of her own in Re: Pasolini:

Of this cover, she observes the following: “All of the gracious Virgin Mary’s senses are concentrated on her child, while the ears of the donkey unconsciously and reflexively register every sound. The instinctive perception of animals is unbiased and undeviating. I can think of no other picture that more touchingly elevates maternal attentiveness and unadulterated hearing to a metaphor.” Therefore, it’s as much the choice of image as its content that inspires us to regard the old as new, and vice versa.

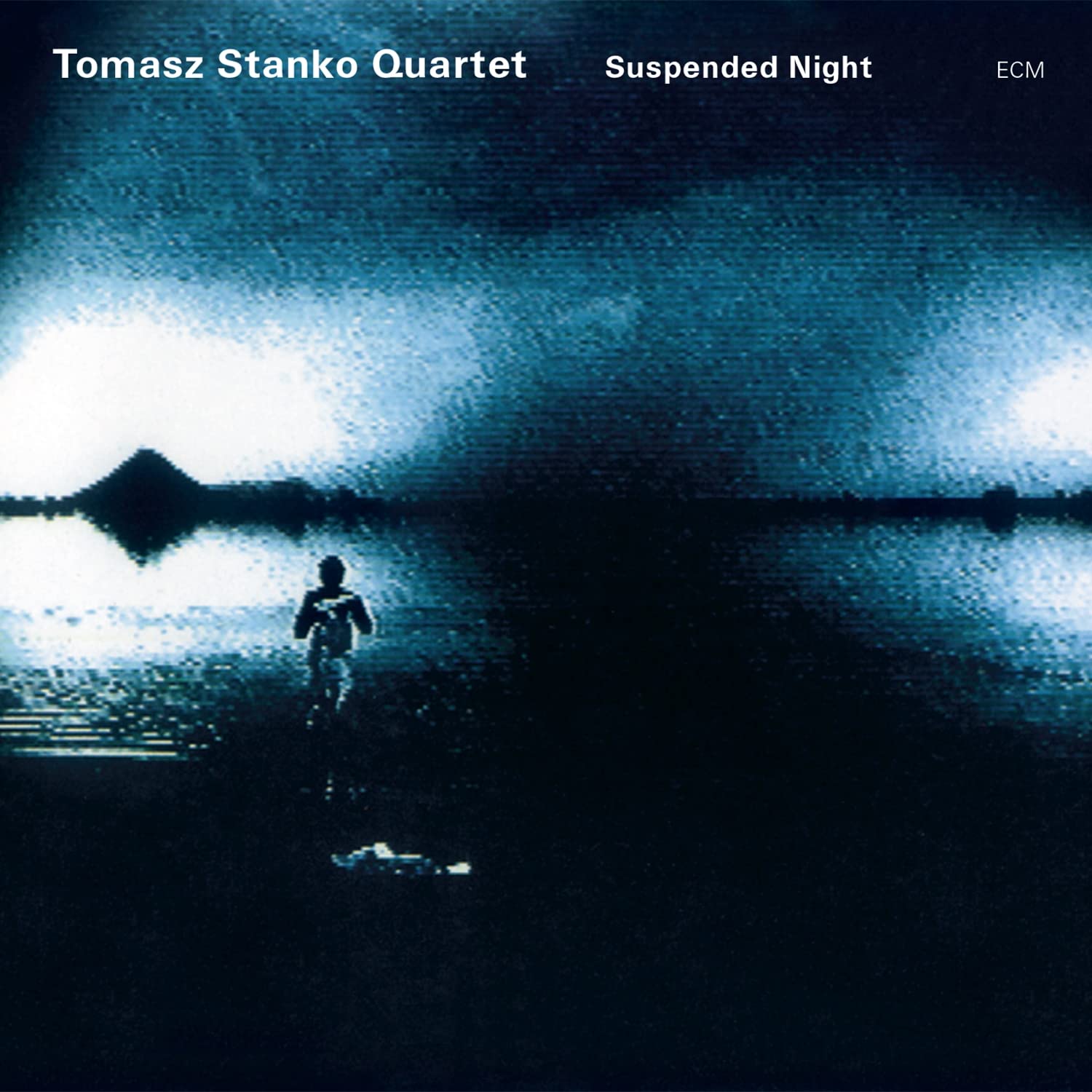

British writer Geoff Andrew takes us yet another step deeper into intersectionality in “Leur musique: Eicher/Godard – Sound/Image.” Here, the concern is with the cinematic awareness that has long been at the heart of producer Manfred Eicher’s approach to mise-en-scène. Because both he and filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard are fond of “juxtaposing, combining and mixing up elements which most people in their respective fields would never dream of bringing together,” it was only natural that Godard’s work would come to be associated with such seminal recordings as Suspended Night, which features a still from his mangum opus, Histoire(s) du Cinema, and Soul of Things, which references Éloge de l’amour:

Where the latter film also gives us Norma Winstone’s Distances, we have the former to thank also for Words of the Angel, Morimur, Requiem for Larissa, Songs of Debussy and Mozart, and Voci.

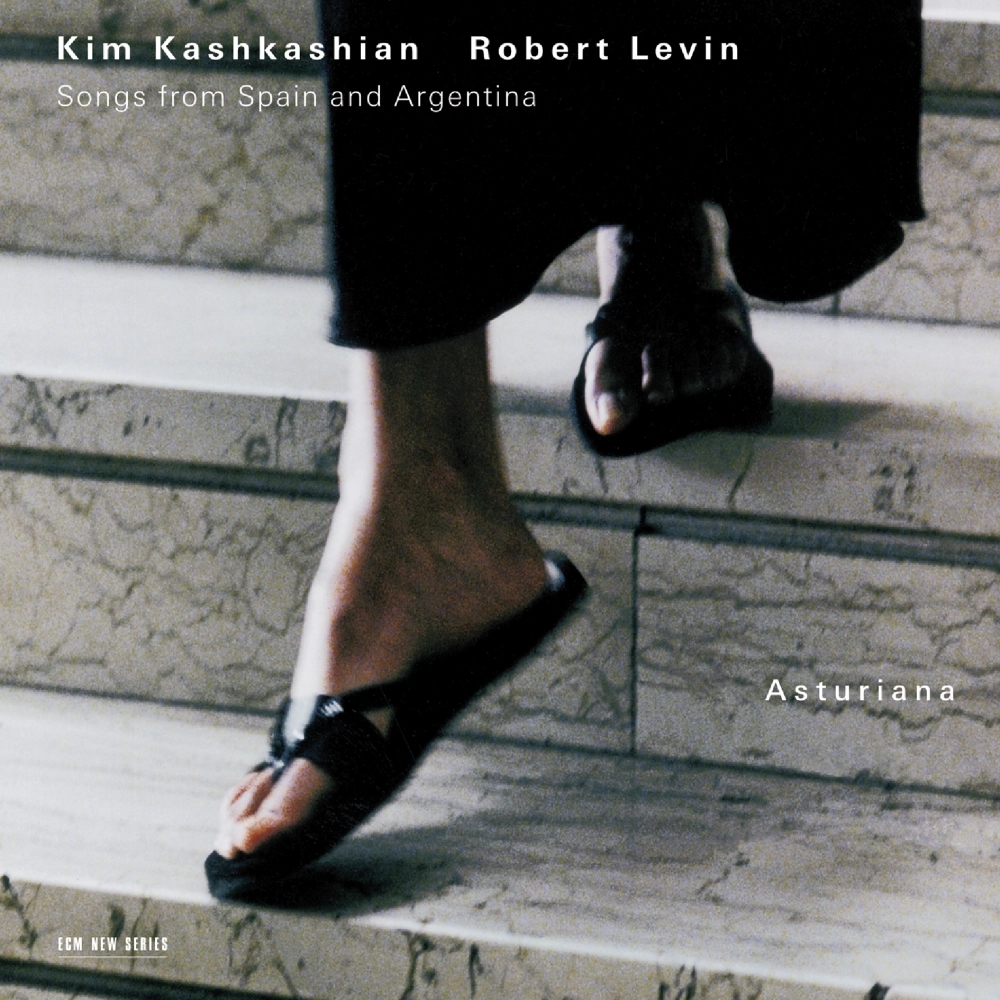

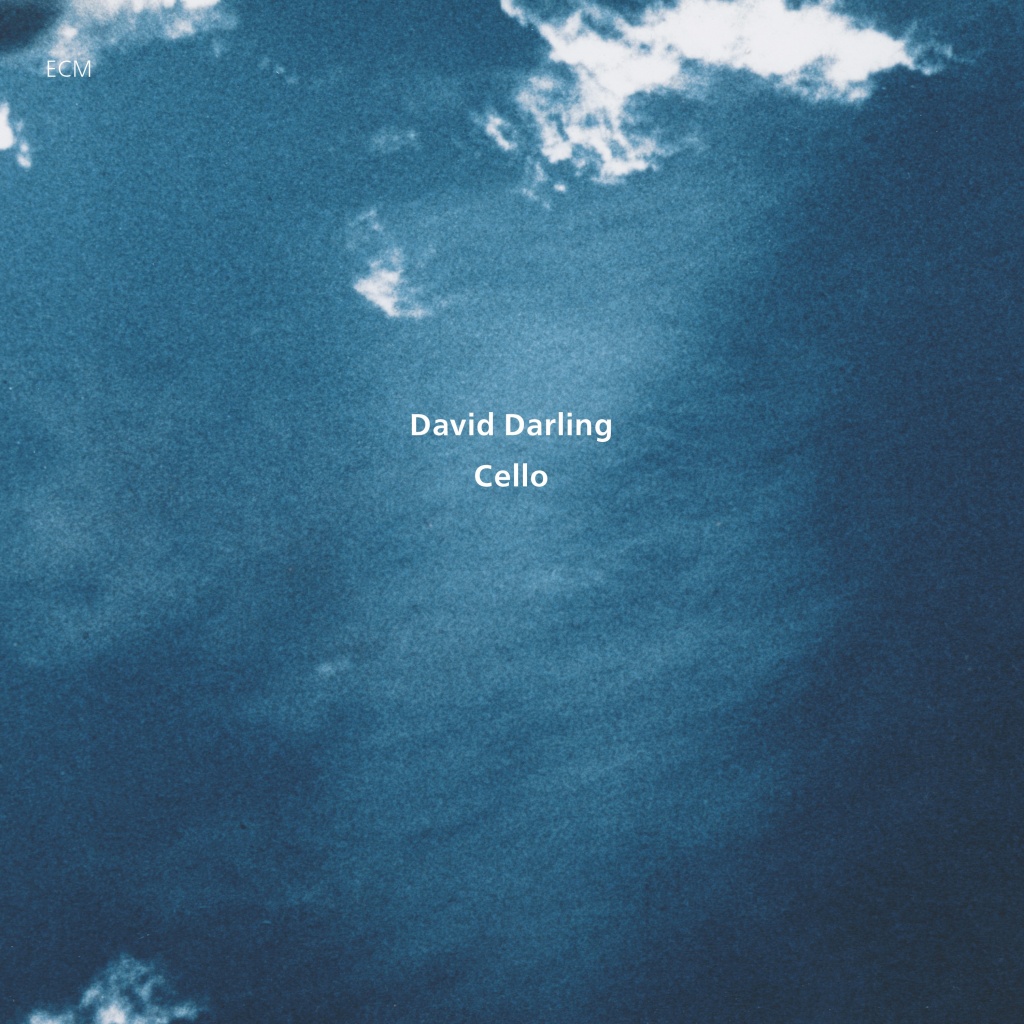

Perhaps not surprisingly, these are already borrowings from other sources—quotations of quotations (and is not classical music the same?). Other Godard touchpoints include Notre musique for Asturiana and Passion for Cello and Trivium.

And let us not forget the soundtracks of Godard’s own Nouvelle Vague and the above-mentioned Histoire(s) du Cinema.

One could hardly imagine such a book as Windfall Light without including the perspective of at least one ECM musician, and in pianist and composer Ketil Bjørnstad, we are given a most suitable ambassador. In “Landscapes and Soundscapes,” he looks not at the spatial but at the temporal. In speaking of the timeless quality of the covers, he notes a preference for monochrome and Nordic landscapes and atmospheres. “Being produced by Manfred Eicher is a purification process for a musician,” he reveals. In so doing, he leaves an implied question hanging in the air: Does a cover photograph or painting also undergo a sort of purification process? When disassociated from its original context, does not the image open itself to infinite possibilities? Bjørnstad again: “Just as great composers and painters are recognizable down to the smallest phrase or brushstroke, ECM’s music and visual world are recognizable without the slightest danger of anyone calling this stagnation.” Thus, the more this recognition settles in our gray matter, the more we come to equate the landscape with the soundscape.

Last but certainly not least is “Polyphonic Pictures” by Lars Müller, whose publishing imprint has given us this fine volume. His offering is a relatively zoomed-out perspective on the questions at hand. Going so far as to describe the covers and music of ECM as “libertarian”—at least in the sense that they elide the intervention of power structures that all too often infect recorded media—he characterizes them as “afterimages of memorized circumstances far more than they are depictions of things that have been seen.” In that sense, they grow with listeners in connection to lived experience. This take resonates with me at the deepest personal level, as even one glimpse of a beloved album cover invokes a reel of memories, associations, and impressions. Rather than their technical aspects, it is their eventfulness, their movement in stillness, and their visceral foundations that make them come alive. And so, in his ordering and layout of the images, he has created for us a self-avowed “visual score.” Ultimately, they are only as delible as the paper they’re printed on, and so they can only live on in the mind’s eye, which, if it’s not obvious by now, is more accurately depicted as an ear.

looks good. G