Mara Mattuschka’s entrance into the world of cinema feels less like a debut and more like a detonation of everything the frame assumes about humanity, language, and the permeable membrane that binds them. Born in 1959 in Sofia, Bulgaria, she uprooted herself at 17 and resettled in Vienna, a city of German syllables at first beyond her command. While acclimating to her new environment, she felt her native words eroding, slipping into an interior exile. What disappeared in speech resurfaced in image, as visual media became the refuge through which she could still articulate her thoughts. She began with short films (“epigrams,” “aphorisms,” and “two-liners”), each a tight blast of vision that compressed poetry into movement. And from the outset, she conjured an alter ego for the screen: Mimi Minus, a persona equal parts mask and reveal.

Gifted mathematically, Mattuschka also studied painting and animation under Maria Lassnig at the University for Applied Arts, where she learned that the flesh could be a medium as honest as pigment. “I use my body as an instrument,” she says. “It is brush, pencil, and thought.” Yet she resists classification as a breaker of taboos, which remain surface-level distractions from the deeper strata where psychological necessity meets material expression. Sex, in her universe, is rarely sex but an assimilation, something closer to action painting than transgression. Her films teem with this notion of “non-verbal understanding,” a physical comprehension of the world that predates and outlives the almighty utterance.

This early philosophy materializes vividly in Nabelfabel (NavelFable, 1984), in which Mattuschka stages a second birth through pairs of tights in what amounts to a ritual and a comedy rolled together into one. Magazine mouths, newspaper masks, notebook-paper credits: all media collapse as she plunges her head into the nylon cocoon and wrestles her way out by means of lips, tongue, and face. Negative images flare; lines are drawn and abandoned. The sound skitters as a distressed record, a creation myth in the form of a self-portrait.

Meanwhile, mischief abounds in Cerolax II (1985), a commercial break from the world’s unconscious, with Mimi Minus hawking a brain-cleaning agent. Writing in black ink on a mirror, she makes herself surface and solvent. Skin becomes animation cel; sprays and marks imply a purging from within, a shedding of psychological residue—“lax” as laxative, but for thought.

In Der Untergang der Titania (The Sinking of Titania, 1985), Mattuschka turns the titular goddess into an outcast, imagining her not as a symbol of fulfilled love but as a woman whose power stems from unrealized desire. A bathtub that should drain becomes fertile instead, filling with ink that shrouds sexuality in shadow. Titania bites an apple, muses on the absence of love, and paints a pear instead. “No one,” she insists, “can understand love better than a woman who may be enjoying it for the first time.” Longing, here, is its own gravitational field.

Likeminded interplay of embodiment and machinery pulses in Kugelkopf (Ball-Head, 1985), Mattuschka’s “Ode to IBM,” where she becomes a typewriter made of flesh. With Carmen blaring, her shaved and bandaged head becomes a stamping device, printing letters and bull’s horns in a swirl of bravado, a typewriter ribbon serving as the matador’s scarf. And outside the window, life ambles on, unaware of the performance above, an oblivious world moving in quiet amnesia.

Mattuschka’s fascination with systems culminates in Pascal-Gödel (1986), a meditation on the union of numerators and denominators. Mimi plays chess on graph paper against her own negative double. Wine pours and reverses with melodramatic impossibility. Ink seeps across the board, thought overrunning form. Silence becomes the only language capable of holding such an equation.

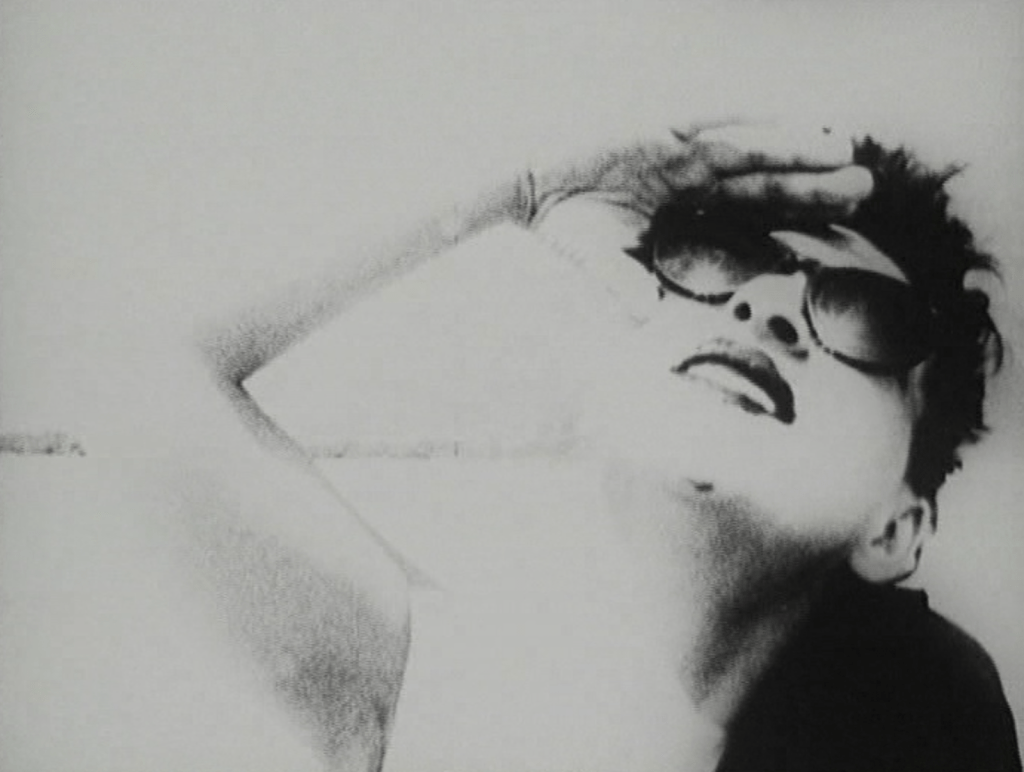

That tension between interior and exterior bodies shifts into nervous-system poetics in Parasympathica (1986), where sweat, tears, ejaculate, and vaginal fluid become a painterly palette. As a male voice muses about butterflies, Mattuschka appears in stark black and white, hovering somewhere between nature documentary and dreamscape. Protection and compromise blur, holding the question open.

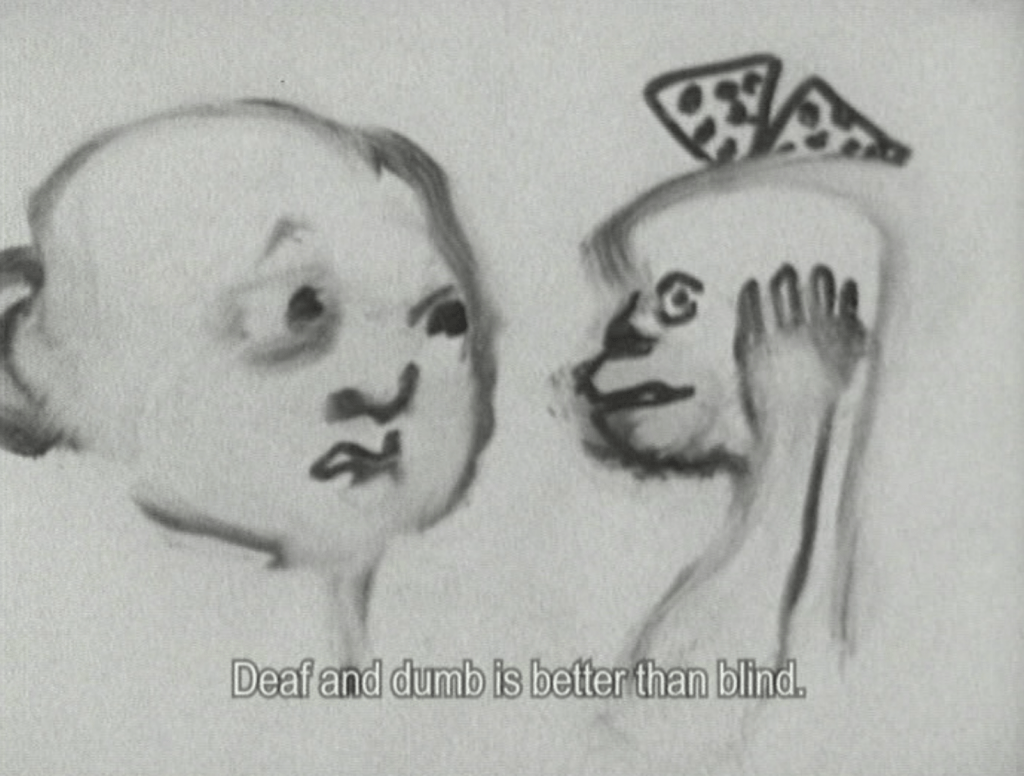

Childhood curiosity takes on unsettling pliability in Les Miserables (1987), animated with water-soluble pigments and the artist’s own saliva. A boy and a girl wander in search of another girl, whose genitalia prompts the question, “Is that real?” Her violation reduces her to vowels, a prelinguistic utterance that is less than language. Set in the impossible year 1001, the film warns that “hearing and sight are easy to blight.” Innocence and injury fold into each other, Mattuschka’s sealing the sequence.

That same year yields Danke, es hat mich sehr gefreut (I Have Been Very Pleased), a hyper-bright faux fashion advertisement shot on a radioactive beach, where she pleasures herself as the camera steadily withdraws. Her climax dissolves into electronic distortion—witchlike, feral, uncontainable.

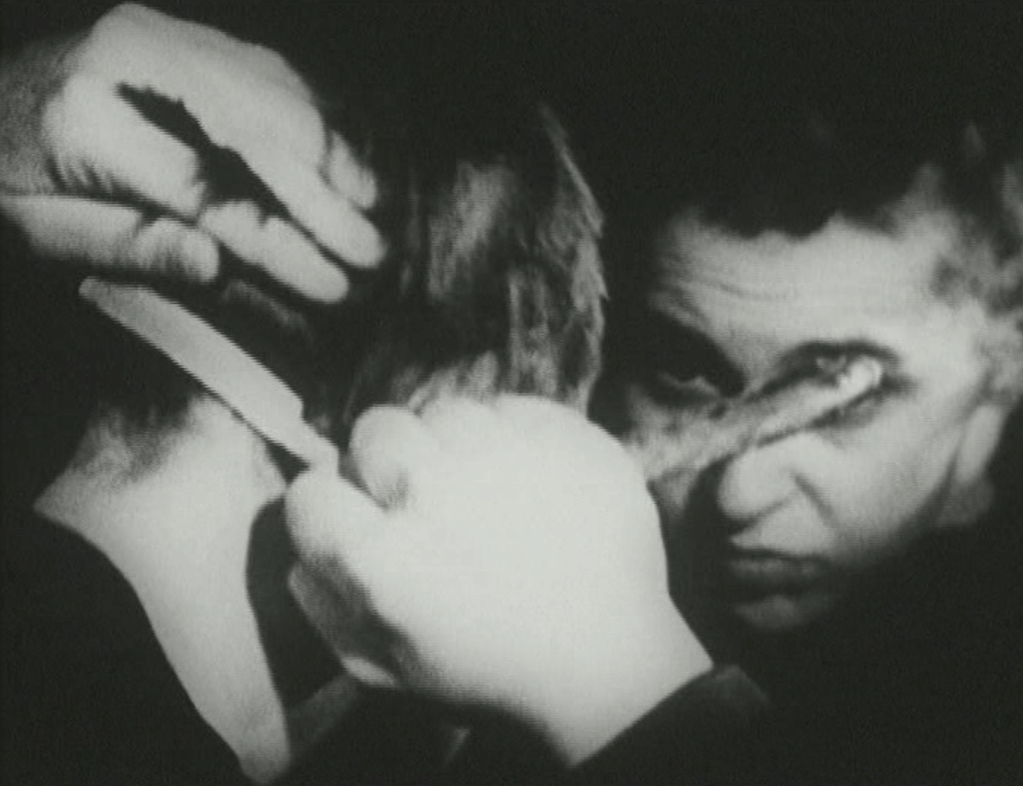

The dissolution of language becomes literal in Kaiser Schnitt (Caesarean Section, 1987), where alphabet soup becomes an anatomical cipher. While she cooks, an EKG line animates across paper. Utensils transform into surgical instruments; the body becomes a site where text is extracted. Mattuschka slices open an ink-filled slit, removes letters with tweezers, and arranges them through a visceral surgery.

In its aftermath, motherhood becomes both a burden and a creative engine in Der Schöne, die Biest (Beauty and the Beast, 1993). A figure climbs a hill, possibly carrying a newborn. Scenes of feeding, climbing, dressing up, reciting poems, and playing a stringless violin evoke a life pulled between creation and constraint. She emerges through a tunnel of cars, as if re-entering the world after an inner voyage.

Her 1993 S.O.S. Extraterrestria turns this negotiation outward, connecting modesty and destructiveness through unseen pipes that thread humanity’s waste beneath the surface. Covered in tights, she regards herself in the mirror, tuned to radio transmissions. Trying on clothing becomes existential calibration. She plays Godzilla, lays waste to a city through superimposition, mates with the Eiffel Tower, and is electrocuted; her voice remains half-formed, exploratory, testing the edges of articulation as everything burns around her.

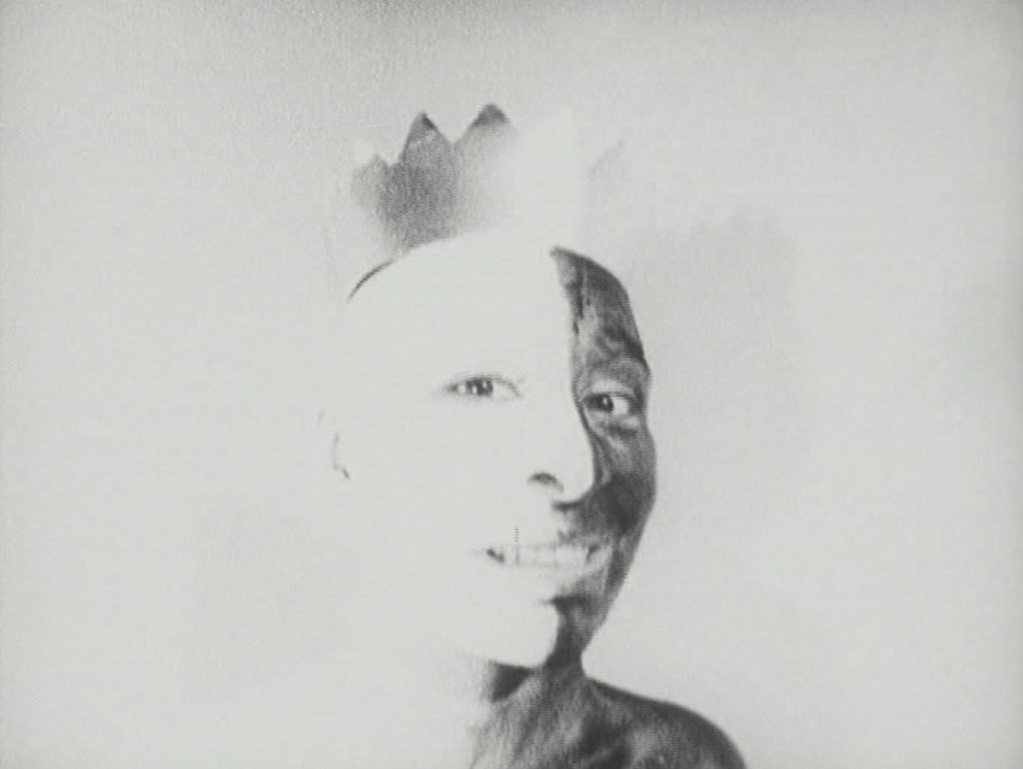

A decade later, ID (2003) plunges into the horror of doppelgängers, mating, and cannibalism. Her voice drones in wordless surges as her face morphs into its own Other, the self dividing and devouring self on a never-ending escalator.

And somewhere at the center of it all sits the modest bonus piece “Ahm…”, a brief self-presentation in which Mattuschka faces the camera and utters only that single suspended syllable. Forever on the verge of speech but withholding the utterance, she captures a moment both uncomfortable and profound, a miniature manifesto of hesitation, possibility, and the unsaid.

Across these works, a single principle emerges: Mattuschka inhabits the body not as a subject but as an instrument that produces meaning through gesture, residue, and metamorphosis. Her films do not break conventions so much as dissolve the structures that make them legible in the first place. What remains is a site of simultaneous vulnerability and invention.

Mattuschka’s cinema suggests that identity is always in revision, never a noun but a verb that bargains with the world’s materials. Her forms multiply, distort, leak, and reform, questioning whether language belongs to the self or vice versa. Meaning begins long before we learn to speak and continues long after words fail. She is an archive, a painter’s brush, a battlefield, an oracle, the first medium and the last. She reminds us that being human means being perpetually unfinished, always pushing against the skin of our own becoming, always trying to articulate something just beyond what we can say. Which is why we are only left with her looking into the camera and saying, “Ahm…” It is the sound of art beginning again.