As She Likes It: Female Performance Art from Austria gathers a constellation of works that respond—sometimes gently, sometimes ferociously—to the long shadow of Viennese Actionism, a movement historically dominated by men and their bodies. Here, however, women reclaim the camera, the gesture, the wound, and the joke. The title insists that these artists act not in reaction to but in accordance with interior tempos. Their works are by turns tender, wickedly funny, uncomfortable, ecstatic, pathos-ridden, furious, and quiet. And in their variety, they refuse the narrowness of being “women artists.” They are simply those who take the body as a proving ground and who understand performance as a way of thinking through.

Maria Lassnig and Hubert Sielecki open the compilation with Maria Lassnig Kantate (1992), a jubilant elegy to self sung at age 73. Lassnig dresses herself in religious, painterly, and folkloric symbols, parading them in front of her own paintings while Sielecki’s hurdy-gurdy churns with medieval charm. She compresses her life into stanzas: violent parents, nuns at school, battling with beauty standards, the struggle for artistic legitimacy. “I painted far better than any man,” she proclaims, and she does so not with resentment but with the grin of someone who has finally learned to embrace her own stubbornness. Her lovers betray her, Paris confuses her, America liberates her, Vienna calls her home: notes composing a symphony in the key of play.

Miriam Bajtala’s Im Leo (2003) burns the eye rather than the ego. A woman stands in a doorway, tilting a mirror so sunlight lashes the camera. Each flare triggers a short electronic beep, like a Morse code sent by the sun. The act is simple but devastating: the woman, refusing visibility, weaponizes reflection. She makes herself illegible by blinding the apparatus meant to record her.

Carola Dertnig makes two appearances. Strangers (2003) stages a chain of embarrassments as a passenger disembarks from a train only to discover that a man’s shoe has trapped a strip of red cloth emerging from her pants. As she walks, it stretches across the station like a lifeline or a humiliating tether. The absurdity recalls Karl Valentin and Liesl Karlstadt’s titular 1940 performance, suggesting that embarrassment is universal—even communal—but always gendered in its consequences.

In byketrouble (1998), from her slapstick series True Stories, a woman tries repeatedly to enter and exit an elevator with a bicycle. Each attempt compounds the farce. A businessman intervenes with civility that only makes the scene more excruciating. Dertnig exposes the fragility of female public presence—the fear of being in the way, the desire to disappear.

Kerstin Cmelka’s Neurodermitis (1998) offers intimacy that feels illicit. The artist applies cortisone salve to her eczema while the camera watches impassively. Voyeurism is found not in what is shown but in how long the viewer must sit with it.

Barbara Musil and Karo Szmit respond to pain with the joy of SW–NÖ 04 (2004), a highlight. The two artists wander through the Austrian village of Reinsberg, stepping into postcard-like paintings, stealing a snack from a farm, picnicking, and playfully resisting the distance that tourism usually demands. When a man films them, their battery dies, as if the camera itself refuses to cooperate with the picturesque.

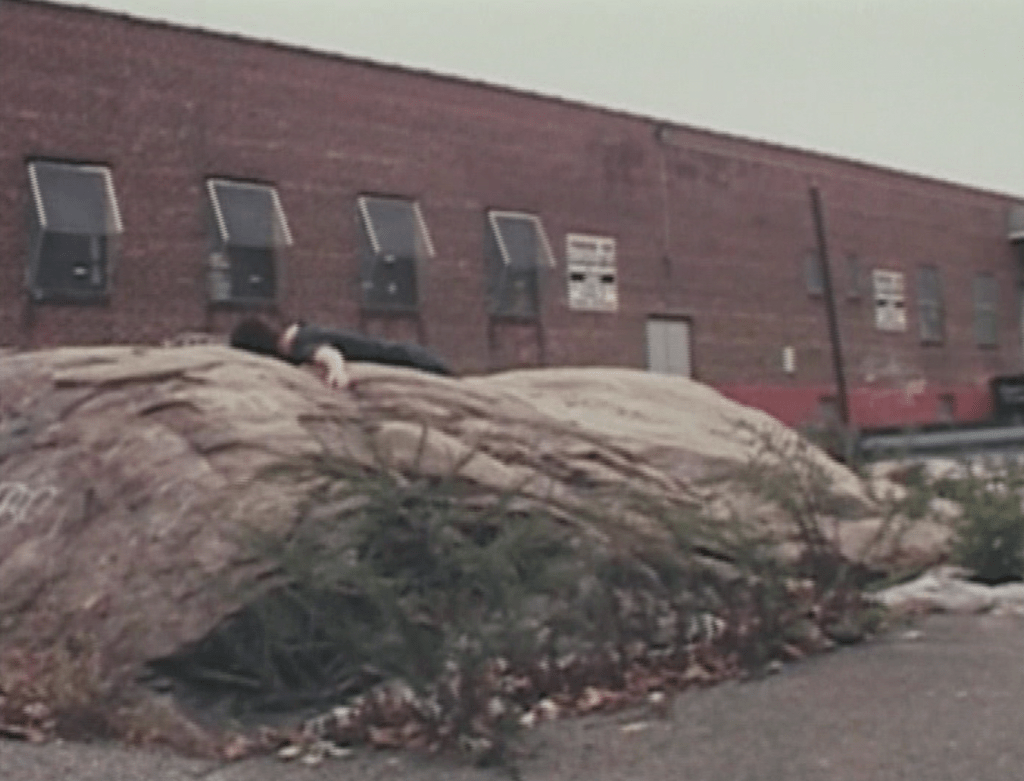

Ulrike Müller’s Mock Rock (2004) finds the artist on a stone mound in Queens, singing, “I am a rock, I am an island…” Müller echoes VALIE EXPORT, affixing herself to the rock as a geological artifact left behind in an urban environment of speed and noise.

Fiona Rukschcio’s schminki 1, 2 + 3 (1998) documents the construction of the feminine face—foundation, lipstick, eyelash curler—interrupted by jump cuts and sound skips. The film ends with a handful of pills and a yawn in a curtain call of exasperation.

The centerpiece of the compilation is Legal Errorist (2004) by Mara Mattuschka and choreographer Chris Haring. It is also one of the most astonishing works in the INDEX catalog. Stephanie Cumming elicits a trance-like disintegration of language and body. She echoes banal conversations, but every phrase catches in her throat. Her limbs jerk as if fighting against the grammar of being gazed upon. She sings “Close to You” with eerie clarity—her one slip into fluency, borrowed from the heterosexual fantasy machine. She speaks of aging, rejection, and the broken machinery of romance. At one point, she stares straight into the camera and says, “What? See?” before thrusting her body toward the lens. “Can you see me?” she reiterates, less a plea than an accusation. The film ends with her receding into darkness, leaving behind the echo of a figure refusing to be reduced.

Finally, Michaela Pöschl’s Der Schlaf der Vernunft (The Sleep of Reason, 1999) is almost unbearable: a single shot of the artist’s face while she is whipped for 14 minutes off camera until she faints. The film is not about pain but about endurance under the pressure of the world’s unseen blows.

The bonus tracks offer various self-presentations, including an unforgettable performance by Mattuschka as “Queen of the Night,” but the compilation as a whole forms the truest chorus in its feminist counter-archive. By shifting its axis inward, it recontextualizes pain beyond the reach of systems that profit from female silence.