Another review by yours truly, this of Kayhan Kalhor and Erdal Erzincan’s recently released Kula Kulluk Yakışır Mı, is now available to read in RootsWorld online magazine. You can read my take on this masterful album here.

World

Stephan Micus: Desert Poems (ECM 1757)

Stephan Micus

Desert Poems

Stephan Micus sarangi, dondon, dilruba, doussn’gouni, kalimba, sinding, steel drums, shakuhachi, ney, sattar, flowerpots, voice

Recorded 1997-2000 MCM Studios

On Desert Poems, Stephan Micus’s 15th solo excursion, the intrepid musical sojourner introduces a few new actors to his already extensive roster of instruments: the doussn’gouni (West African harp), kalimba (Tanzanian thumb piano), and dondon (Ghanaian talking drum). These he nestles among more familiar veterans: his modified 10-string sarangi, dilruba (another bowed instrument from India), ney, and sattar (an upright Uighur fiddle). As always, Micus is attentive to the Janus nature of the instruments he touches. On the one hand each has a history, while on the other it enables new paths of expression. He embraces both as equals.

Characteristic histrionics speak of a thousand other worlds in “The Horses of Nizami” (for sarangi, 5 dondon, and 23 voices) and in “Mikhail’s Dream” (2 kalimba, voice, sinding, 2 steel drums, percussion). In these multi-tracked biospheres, a self divided becomes a self magnified and therefore needs its own language to breathe properly. Indeed, at Micus’s touch the sarangi body becomes a wooden lung through which a chanting chorus activates its array of sympathetic strings. Buzzing kalimba then glow with firefly steps, a ladder of light into the rising dune heat. Amid this flowering conference of souls, a single voice rises into, even as it drops down from, the ether and places its song on a fulcrum of memory and future paths.

The blood of this album’s earthly incarnation is purified by “Adela” (for 22 dilruba), for it speaks of a mirroring heaven in which all that has come to pass awakens to the possibility of a self-aware now. These sounds take human shape: a warrior walking upside down, feet treading sky, his horse long dead behind him, turned to cloud and dropping rain somewhere on more fertile land. With a grating pulse, he marks his footfalls by way of a dotted moon. By nightfall, only his afterimages remain, thrumming in the counterpart of “Shen Khar Venakhi” (6 dilruba, 6 sattar), a 13th-century choral piece from Georgia which Micus arranges in wordless tonsure.

“Thirteen Eagles” (doussn’gouni, 20 ney) and “For Yuko” (2 flowerpots, 8 voices, shakuhachi) share another soul. One is a blissful trek over land and under emotion that focuses purely on movement and shape, ney pleated many times over like feathers and free as heroines of the open sky. The other bears dedication to the performer’s daughter in a galaxy of nascent voices, hurtling through space along a trajectory of sentience and love.

If these are the internal organs, three solo tracks comprise the external features. The eyes flicker into being by way of “First Snow.” Although not a title one might expect amid all this warmth, the continuity is not lost. Its lone shakuhachi is an arid instrument. Cored and lacquered, it rasps like wind through wheat and digs through the soil with deeply grained fingertips. Its song dreams of water, and like the snow remains dry until the warmth of sun or living touch renders it fleeting. Lips speak in “Contessa Entelina,” a voice solo in English that is named for, and inspired by, a village Micus encountered while riding through the Sicilian countryside, and tells the story of a countess who provided solace to Albanian immigrants some centuries ago. This intimate portrait folds perfect divinity into the imperfect cage of human language and means. Ears listen in “Night,” a far-reaching doussn’gouni reflection that bears gifts from the heavens to the caverns.

Seemingly enamored with the same consuming silence of the desert that captured the heart of writer Paul Bowles, Micus translates the hidden energies of landscape into a form that escapes all measure of mortal grasp. World music? Perhaps. But not entirely of this one.

A selfless masterpiece.

<< Joseph Haydn: The Seven Words (ECM 1756 NS)

>> Dave Holland Quintet: Not For Nothin’ (ECM 1758)

Claudio Puntin/Gerður Gunnarsdóttir: Ýlir (ECM 1749)

Claudio Puntin clarinet, bass clarinet

Gerður Gunnarsdóttir violin, vocal

Recorded 1997-99 at Radio Bremen, Sensesaal

Engineers: Dietram Köster and Christine Potschkat

Recording producer: Peter Schulze

Co-production ECM Records/Radio Bremen

Claudio Puntin and Gerður Gunnarsdóttir make their ECM debut with Ýlir, a musical portrait of Iceland utilizing a mixture of techniques, realities, and understandings of that fabled volcanic jewel. Gunnarsdóttir, a violinist and vocalist of eclectic professional associations, calls Iceland home, while clarinetist Puntin hails from Switzerland. The latter also possesses a wide-ranging talent across idioms, and has continued his association with ECM as a regular member of the Wolfert Brederode Quartet. As a duo, these partners operate under the moniker Essence of North, folding seamless improvisations into a batter of original and traditional material, but always with an ancestral taste on the tongue. The culmination of all this is a unique chamber recital of magical dimensions.

Puntin and Gunnarsdóttir seem most in their element when there are stories to be told. In particular, “Huldufólk”—literally “hidden people” but translated more colloquially as “fairies”—speaks to a world within a world, a world from which the duo draws its breath and feeds an interpretive grace back into the hollows. The piece takes shape in three divided parts. “Draumur” (Temptation) and “Tæling” (Seduction) each open a blank diary and inscribe it with mythological phonemes, a siren’s song in points and lines. Here, as elsewhere throughout, the clarinet embodies an unsuspecting Alice. The violin, meanwhile, slithers Cheshire-like across an outstretched branch, leaving a trail of streaking teeth and fur. “Hringekja” (Whirligig) finishes with a dance on a miniature scale, leaping up fungus steps and swinging from dripping leaves.

Evocative highlights include “Hvert örstutt spor” (Each Little Step), for which Gunnarsdóttir sings words by Icelandic writer Halldór Laxness, winner of the 1955 Nobel Prize for literature, as adapted by Darmstadt disciple Jón Nordal. This forlorn song for voice and bass clarinet closes our eyes in anticipation of “Sofðu unga ástin min” (Lullaby For An Abandoned Baby), a thrumming folk tune. “Kvæðið um fuglana” (Fantasy About Birds) is another visceral episode. This piece by Atli Heimir Sveinsson, a composer whose interest in folk music bears ripe fruit, positively glows in Puntin’s arrangement.

Whether the ebony drones of “Einbúinn” (The Ermite) and “Enginn láì öðrum frekt” (Contemplation), the Lena Willemark-esque excitations of “Peysireið” (Gallop), or the blend of near and far that is “L’ultimo abbraccio” (Last Embrace), there is much to explore in these vignettes. In the title track a pliant violin draws footpaths in snow (“Ýlir” means “winter”), joined by a clarinet that sings with memories of autumn. Like a bird caught in a blizzard, it ululates in the throes of indecision, thus giving melodious name to isolation. The yang to this yin comes with “Leysing” (Melting, Thaw), which sounds as if someone had placed a microphone inside a spring landscape and recorded its renewal. Through scrapings and lilting phrases, the musicians find a treasure trove of messages lurking below, just waiting to see the sky above and reach for it while they still can. In “Vorþankar” (Reflections On Spring), too, the harshness of winter is softened, glistening off icicles as if they were instruments, each a note with its own song to sing. Resonant and glassine, they waver at the edge of waking, like the lonesome goodnight of the “Epilogue,” a kiss forever locked on the lips of the moon.

All in all, this storybook journey peeks through the trees even as it uproots them, one microscopic tendril at a time, and with them strings a loom of thick emotions. Worth seeking out, if it hasn’t already sought you.

<< Eberhard Weber: Endless Days (ECM 1748)

>> Suite For Sampler – Selected Signs II (ECM 1750)

Anouar Brahem: Le Voyage de Sahar (ECM 1915)

Anouar Brahem

Le Voyage de Sahar

Anouar Brahem oud

François Couturier piano

Jean-Louis Matinier accordion

Recorded February 2005, Auditorio Radio Svizzera, Lugano

Engineer: Stefano Amerio

Produced by Manfred Eicher

The music of Tunisian oud virtuoso Anouar Brahem and his trio with pianist François Couturier and accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier is like a magical box of movable type in which the letters form alluring, coherent stories no matter how one arranges them. The printing press this time around may be of similar make to the preceding Le pas du chat noir, but the themes are even more narratively inflected by virtue of the trio’s evolving magnetism. The strength of Brahem’s visual imagination comes strongly to the fore whenever he sings. Although wordless, his voicings on “Les jardins de Ziryab” and “Zarabanda” fold water into sand, painting cycles of intervallic bliss. The chant-like quality of his melodizing buoys Matinier’s soaring exegeses, thus providing an aerial view of the album’s intimate topography. Further whispers abound in the album’s opener, “Sur le fleuve,” which establishes a signature sound of lilting pulse and unseverable braid. As in the gentle persuasions of the title track, Brahem’s suspended steps give his associates just the shade they need to unravel their filmstrips without fear of overexposure. Each of the oudist’s wistful solos is a message in a bottle, Couturier’s chording the foamy currents it rides, and Matinier’s cries those of the recipient standing on a distant shore.

Ensuing atmospheres range in density: from the enigmatic “L’Aube,” as fragile as a mirage, to the restless abandon of “Cordoba,” each samples a different time and space in a sepia-tinted world of streets and blurred visages. Sometimes, the directions are clearer, as in “Eté andalous,” which begins in the mountains and flows down to the mainland. Other times, the music’s robust heartbeat finds balance in meditative poses and parabolic expression. Whether running across the plains of “Nuba”—each dig into the oud’s lower register a puff of kicked-up clay—or drowning in the insomnia of “La chambre,” these are ever-thoughtful alternate realities.

Rounding out the disc are three of Brahem’s most requested tunes, freshly realized. “Vague” and “E la nave va” form a diptych (the former revived from its appearance on Khomsa). With the regularity of a train warning sign, two red eyes alternating winks in the night, it crosses hands until one body is indistinguishable from the other. “Halfaouine” (cf. Astrakan café) is a brief yet luminescent passage of cascading beauty, the swirl of grounds at the bottom of a coffee cup.

The Anouar Brahem Trio wears a skin of gold, sings with a tongue of silver, and moves in gestures invisible. And whatever it chooses to communicate, one can always be sure its language needs no translation.

Anouar Brahem: Le pas du chat noir (ECM 1792)

Anouar Brahem

Le pas du chat noir

Anouar Brahem oud

François Couturier piano

Jean-Louis Matinier accordion

Recorded July 2001 at Radio DRS, Zürich

Engineer: Martin Pearson

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Oud virtuoso and composer Anouar Brahem returns to ECM with an inspired trio. In the company of pianist François Couturier and accordionist Jean-Louis Matinier, he emerges more as guiding wind than guiding light, forging a quietly original program that feels at once unprecedented and timeless. Brahem’s writing is especially intuitive on this outing, teetering from stream-of-consciousness currents to insightful themes in the steady arc of a summer fan.

Le pas du chat noir brings a desert’s clarity to the night air, exposing an intricate carpet of stars against cloudless sky. The color schemes are simple, but their constellations sway with deep mythology. The opening title track lacquers a table for all the puzzle pieces that follow: raindrops turned images, fragments of a whole. As in the concluding “Déjà la nuit,” its surface trembles ever so slightly from the weight of a nearby spirit’s footsteps. Of this small mountain of twelve pieces, “Leila au pays du carrousel,” which appears once properly and again in variation, is the apex. Its arpeggios tip a quill’s inkwell, pregnant with potential words. Accordion and piano configure every fractal edge, a galaxy in miniature. With their turning comes forgiveness, the unerring stare of divinity that clasps its fate around all life and breathes until it shimmers. A Philip Glass-like ostinato from Couturier lends similar regularity to “Les ailes du Bourak,” forming with the others a caduceus of song. Both tunes reveal a distinct new edge to Brahem’s instrument. Be it an effect of the playing or the engineering, its tone is prominently exposed—all the more wondrous when one considers just how shadowy Brahem’s presence is throughout. He lifts the veil, only to reveal another, this made of refraction, prisms of selfless, creative spark.

Notable also are Brahem’s duets. With Couturier he achieves clearest solidarity in “De tout ton cœur,” while in “Pique-nique à Nagpur” he and Matinier skip through the album cover’s trees, their shadows pulling the sky like an eyelid, neither sleeping nor awake. Couturier casts lighter magic in “C’est ailleurs” (which, with its broad strokes and intimate pairings, says much with little) and reads the ether like a sacred book of Gurdjieff in “Toi qui sait.” Such are the nomadic ways of these travelers, each evoking a staggering range of topographies in his fleet passage. As in the first high notes of “L’arbre qui voit,” their leaves fall in slow motion, blown from settlement to settlement in search of a branch.

All the above being said, I might not recommend this as your first Brahem experience. A cup of tea at the Astrakan Café might be in order before taking a stroll down this leisurely, though undeniably beautiful, thoroughfare.

<< Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber: Unam Ceylum (ECM 1791 NS)

>> Zehetmair Quartett: Robert Schumann (ECM 1793 NS)

Anouar Brahem Trio: Astrakan café (ECM 1718)

Anouar Brahem

Astrakan café

Anouar Brahem oud

Barbaros Erköse clarinet

Lassad Hosni bendir, darbouka

Recorded June 1999, Monastery of St. Gerold, Austria

Engineer: Markus Heiland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Tunisian oud master Anouar Brahem has singlehandedly rewritten the history of his instrument, elevating its status to self-contained orchestra. Like a film director whose camera is a third eye, he paints in moving images—no coincidence, given that much of his music is written for screen and stage. His virtuosity is the pulsing stuff of life and therein lies the power of his music, itself a language beyond the grasp of this meager orthography. Astrakan Café is among his best records, for the solemnity of its nourishment is as attuned to the ether as the two musicians who aid in Brahem’s quest to describe its taste. Turkish clarinetist Barbaros Erköse returns after his invaluable contributions to Conte de l’incroyable amour, intense as ever in the spine-tingling depth of his song. Percussionist and longtime Brahem collaborator Lassad Hosni brings likeminded expertise to the table, adding just the right dash of spice to every tune.

Of those tunes we receive a lavish tale, each chapter a depth-sounding such as only Brahem can elucidate. As a meeting place, the titular café lends itself to intimate conversations and a feeling of community across borders. It introduces us to the protagonists of an epic, cohesive narrative. Erköse’s opening gambit in “Aube rouge à Grozny” cuts straight to the marrow, his notes captured at the height of their emotional density. If this is the defining of a door, the title track is the opening of it. Brahem’s plectrum takes its first dance steps into the morning, the streets fresh with vendor smoke and tourist chatter. Beyond them is “The Mozdok’s Train,” in which the trio comes together in the spirit of travel, not as outsiders but as those whose home is wherever they happen to be: disciples to no one but the steps they have yet to take. Brahem chooses his words carefully. He rallies heroes and villains, spirits and the lowly, in a single breath and submits them to his verbal employ. Little do the passengers know that in the next car over, wedged between a folded shirt and a thumb-printed map, is a box of “Blue Jewels.” Brahem sets the stage as Erköse inlays the clasp that keeps those secrets locked. Hosni jacks up the train’s speed. His are the fingers drumming on the stretched leather of a many-stickered suitcase, the conductor’s practiced hand on burnished controls. A memory assails this assailant, a vision of love long buried until now. It awakens in him the will to change in “Nihawend Lunga,” which moves at a clip so untouchable that its eyes bleed silk, a spider’s web for the prey of “Ashkabad.” Erköse flings cries backward and sideways, writhing in the vision of a life he could have had. And just before the train drowns in the darkness of a tunnel, he jumps from an open door and into the mirage of “Halfaouine.” He awakens to the themes of a passing caravan and clutches his prize even as the “Parfum de Gitane” seeks him out like a desert oasis. He listens to the elder sharing tales in “Khotan,” a solo track from Brahem. Youth returns in “Karakoum” as if time has reversed. This lifts his spirit to the realm of “Astara.” Here feet tread lightly but surely, using mountains as stepping-stones to walk across distant suns. Erköse’s haunting monologue, rendered in hourglass shape, inspires a measured line of flight through the alleys of “Dar es Salaam,” across the waters of “Hija pechref,” and back to the album’s title scene, sipping at the bitter fruits of the earth until these fantasies become apparent to us, ephemeral like the swirl of cream that pales into sepia drink.

<< Heinz Holliger: Schneewittchen (ECM 1715/16 NS)

>> Mat Maneri: Trinity (ECM 1719)

Anouar Brahem: The Astounding Eyes Of Rita (ECM 2075)

Anouar Brahem

The Astounding Eyes Of Rita

Anouar Brahem oud

Klaus Gesing bass clarinet

Björn Meyer bass

Khaled Yassine darbouka, bendir

Recorded October 2008 at Artesuono Studio, Udine

Engineer: Stefano Amerio

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Between Rita and my eyes

There is a rifle

And whoever knows Rita

Kneels and prays

To the divinity in those honey-colored eyes

–Mahmoud Darwish (1941-2008)

Anouar Brahem’s The Astounding Eyes Of Rita belongs right next to Tomasz Stanko’s Dark Eyes in that sparsely populated category of great ocular titles. Its blend of oud, bass clarinet, bass guitar, and hand drums nests firmly in an outer skin that welcomes all hemispheres into its audible signature. As one of the world’s greatest living masters of the oud, Brahem has thoroughly absorbed its many lives and draws upon them at a plectrum’s touch. Yet he has also done a phenomenal thing, revitalizing the instrument’s musical possibilities through and beyond the very traditions that inform it. Rita represents a mode of composition (all the music here is his own) that he has come to favor: namely, sitting with his oud and letting it sing to him until moved to capture on paper a glint in its endless melodic river. From such seeds he has nurtured a cohesive eight-part program that pools the talents of percussionist Khaled Yassine (playing here mainly the darbouka, or goblet drum), bass clarinetist Klaus Gesing (heard previously on Norma Winstone’s Distances), and electric bassist Björn Meyer (of Nik Bärtsch’s popular Ronin outfit): four as one, joined at the fulcrum like a card twice folded.

Meyer is an especially creative addition. His snaking incense smoke adds a touch of groove to the album’s bookends (“The Lover Of Beirut” and “For No Apparent Reason”) while also emboldening the most personal reflections (e.g., “Waking State”) with due attention and insight. He is nowhere so integrated, however, than in the engaging “Dance With Waves.” Because of him, an otherwise translucent veil thickens into full-blown tapestry, splashed with burnt sienna and vermillion. These are waves internal, drawn not on water but in blood, spoken in the signs of love.

Yassine is another revelation. He reads into every action of his fellow musicians as if it were a dance, painting his entrances carefully as light breaking cloud. Fans of Omar Faruk Tekbilek are sure to feel at home in the way percussion and oud converse throughout Rita, most notably in the title track and in the more absorbent “Al Birwa.” Gesing, for his part, airs his feathers dry in the warm air of “Galilee Mon Amour” and gilds “Stopover At Djibouti” with lilting filigree.

Brahem, however, is the sun of this particular galaxy. His exciting use of harmonics, as in “Stopover At Djibouti,” adds notable color to an already evocative style, weaving through bustling crowds even as he paints them. We can practically feel his mind working and reworking every stone beneath their feet until it offers safest passage. Inspired as much by everyday life as by the dreams that warp it, he focuses on the spaces between the strings, shaping the air that whispers through them into full-fledged texts. His plucking brings a diacritical edge to their base forms, glyphic and real.

(To hear samples of The Astounding Eyes Of Rita, click here.)

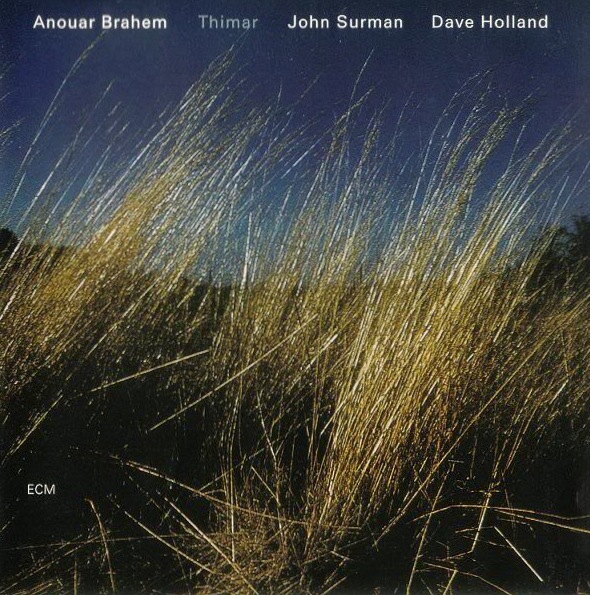

Brahem/Surman/Holland: Thimar (ECM 1641)

Anouar Brahem oud

John Surman bass clarinet and soprano saxophone

Dave Holland double-bass

Recorded March 13-15, 1997 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

The moment’s depth is greater than that of the future.

–Rabia of Basra (714-801)

Oudist Anouar Brahem brings his passion for past and future together in the present recording with reedist John Surman and bassist Dave Holland. Although he has singlehandedly revived the oud as a solo instrument, collaboration has always been at the heart of his craft, whether between himself and the spirit that moves him or with the muses of others. Most of the material on Thimar is Brahem’s and its lack of chording and bar lines in the scores presented Holland and Surman with new and fruitful challenges. One would hardly know it from the fluidity of the session. The album’s title means “fruits” in Arabic and, like those on a tree, the tunes it designates aren’t so much blended as connected by bark, water, and minerals. The press release cites recent musicological research which suggests that jazz may have its roots in the Middle East, for the West African musical traditions it mined were already syntheses of Islamic influences. This is not a “fusion” project. It is an illumination of roots.

Brahem also brings a love of Surman and Holland’s work, introduced to him by way of producer Manfred Eicher, notably through Road To Saint Ives and Angel Song. We might not be wrong, then, in shelving Thimar alongside those ECM gems. The latter of the two is especially ripe for comparison, as it likewise pushes jazz envelopes in an intimate, percussion-less setting. Only here, the added element of Brahem’s keen restraint breeds an enchantment of a different order. Despite his centrality in the program that unfolds, it is some time before he enters the stage. Instead, “Badhra” opens with an adaptive, harmonium-like drone from Holland and Surman’s buttery soprano wafting in the breeze. Holland melts into a solo that rises from the earth, soil made flesh. One might say he treats his bass like an oud, so that when Brahem appears at last it feels like a natural extension—youth to ancestor—and renders Surman’s intonation all the more calligraphic for its contours.

Surman is formidable in this setting, not by means of technical flourish but more so by the movement of his playing. He scribbles masterfully in “Mazad,” bringing an ever-deepening sense of destination to perhaps the most recognizable soprano in recorded sound. That singing reed has hardly sounded better. He further provides a lone interlude in “Waqt,” and one original, “Kernow” (Old English for “Cornwall”), in which his bass clarinet shadowdances with oud.

Holland’s contributions are equally profound. His walking lines in “Kashf” inspire a unified sermon from the trio and plunk like amplified raindrops from leaf to leaf in “Houdouth.” He is an accommodating and adaptable soul, especially in “Talwin,” where his drum-like sensibilities bring rhythmic drive (as they did in Angel Song) to the exchanges swirling around him.

For all the highs and lows, Brahem remains the ultimate truth of these proceedings, our guide on a journey he defines as he goes along. The heart-to-heart tunefulness of “Uns” pins the album’s ethos on its sleeve, evoking villages and bustling metropolises alike. In “Qurb” he adds metallic taste to Holland’s protracted Brew and sings into the tunnel. His “Al Hizam Al Dhahbi,” with its fluid doublings and harmonies, is the session’s crown, a memory in the making. There is a locomotive circuitry in his writing that runs all the way through “Hulmu Rabia” (Rabia’s Dream), signing off elegiacally with a nod to the first female mystic of Islam.

Thimar holds a coveted place in my listening life, for it was my first time hearing each of its three musicians. Separately, they are powerhouses of influence in their respective fields. Together, they are like the cover photograph: Holland the silhouetted land against Surman’s gradated sky, and Brahem the strings hatching their meeting at dusk.

<< Keith Jarrett: La Scala (ECM 1640)

>> OM: A Retrospective (ECM 1642)

Stephan Micus: The Garden Of Mirrors (ECM 1632)

Stephan Micus

The Garden Of Mirrors

Stephan Micus voice, steeldrums, sinding, shakuhachi, suling, nay, tin whistles, percussion

Recorded 1995-96 at MCM Studios

Just as one look at the many instruments Stephan Micus plays is sure to impress, so too does one experience of what he produces with them dispel arbitrary interest in those means. Music flows from his fingertips in such an organic way that the source catches light in all of us. Nothing feels out of place. It’s worth noting, however, that The Garden Of Mirrors makes especial use of that most intuitive instrument of all: the human voice. Like water in sunset, Micus’s wordless songs collect light-years of travel along the glittering surface of their multiplication. Twenty such voices manifest themselves first in “Earth.” Accompanied by the bolombatto, an African gut-stringed harp, this world traveler speaks to the very marrow of life. A binary star leaves his lips, the being to our nonbeing. These twins become triplets, and so forth, until the galaxy is alive in a choir whose rhythms are the stuff that binds. “Violeta” and “Night Circles” exchange the bolombatto for its hemp-stringed cousin, the sinding, melting into a future where hope may breathe like an autumnal wind through leaves. Dry and crackling fields shape syllables with the ferocity of a linguist. Vocal flocks outline the sky in chalk, coloring it in like the white of a giant eye. Veins become songs. These become the world. “Passing Cloud” bands steel drums, two sinding, and shakuhachi for a sound at once vapor-like and heavy as soil. Those who are content see in it animals, trees, and faces, while others see sighs, depressions, and hardships. For “Flowers In Chaos” we get a coterie of 22 suling (Indonesian bamboo ring flutes), dispelling that very cloud with tales of earthly things. “In The High Valleys” is the album’s most insightful contemplation. In its intimate pairing of sinding and voice, it moves, to reference an album title of the Alial Straa, in a lumbering intransitive dream, and would seem to invoke the origin myth of the jazz bass. “Gates Of Fire” marks its passage with ashen footprints, bringing atonement in circular motions, each a brand on the side of a mountain. “Mad Bird” is a living solo for Irish tin whistle that traverses its own boundaries in search of landing, for life on the wing desires stillness. This singles out the final “Words Of Truth,” where the breath of life courses through six shakuhachi in self-reflective bliss. It is the sailor and his reflection, the storm and its rainbow, caressing the shores of a fading continent, of which we are the only inhabitants left standing.

<< Arild Andersen: Hyperborean (ECM 1631)

>> Bjørnstad/Darling/Rypdal/Christensen: The Sea II (ECM 1633)