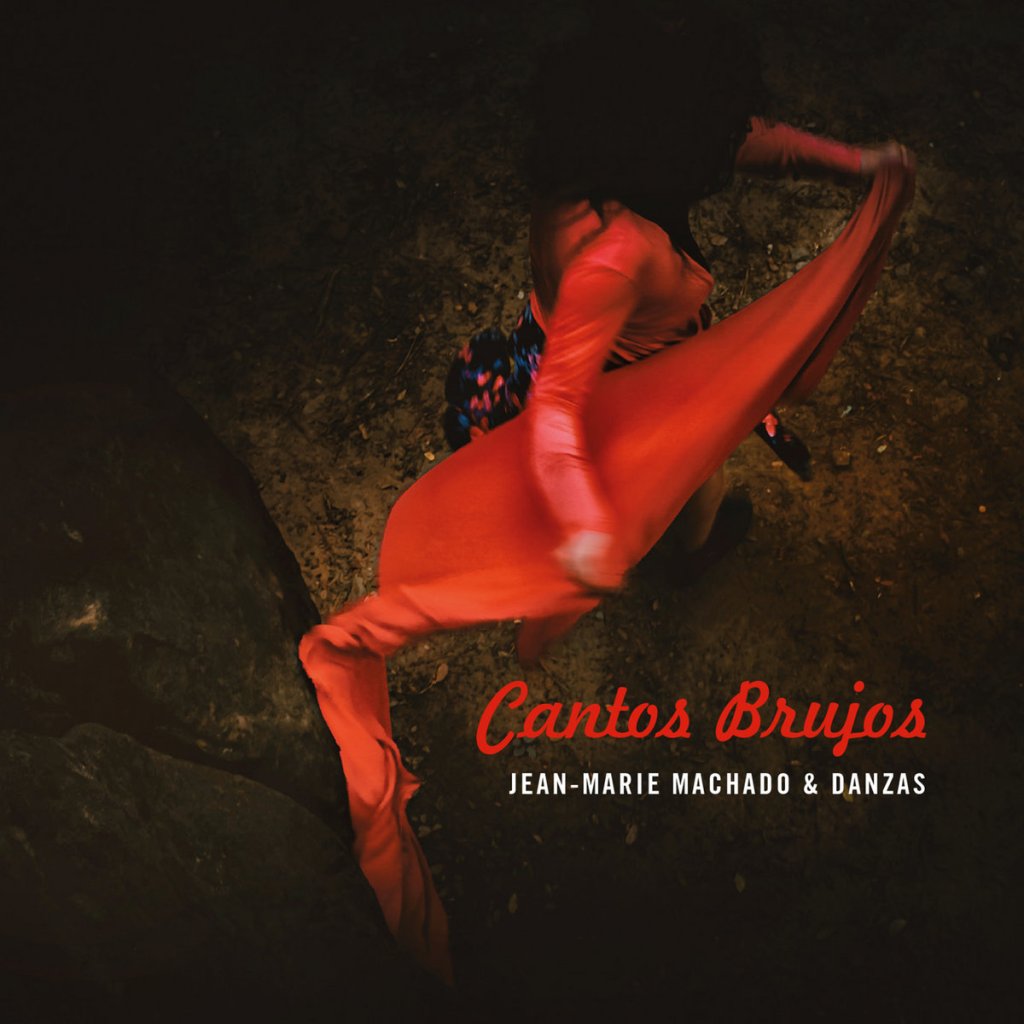

Jean-Marie Machado piano

Karine Sérafin voice

Cécile Grenier viola

Cécile Grassi viola

Guillaume Martigné cello

Élodie Pasquier clarinets

Jean-Charles Richard soprano and baritone saxophones

François Thuillier tuba

Didier Ithursarry accordion

Zé Luis Nascimento percussion

Recording, mixing, mastering at Studios La Buissonne, Pernes-les-Fontaines, France

Recorded September 7-9 and mixed September 21-23, 2022 by Gérard de Haro, assisted by Matteo Fontaine

Mastered by Nicolas Baillard at La Buissonne Mastering Studio

Steinway grand piano prepared and tuned by Sylvain Charles

Produced by Cantabile and Gérard de Haro & RJAL for La Buissonne

Release date: February 24, 2023

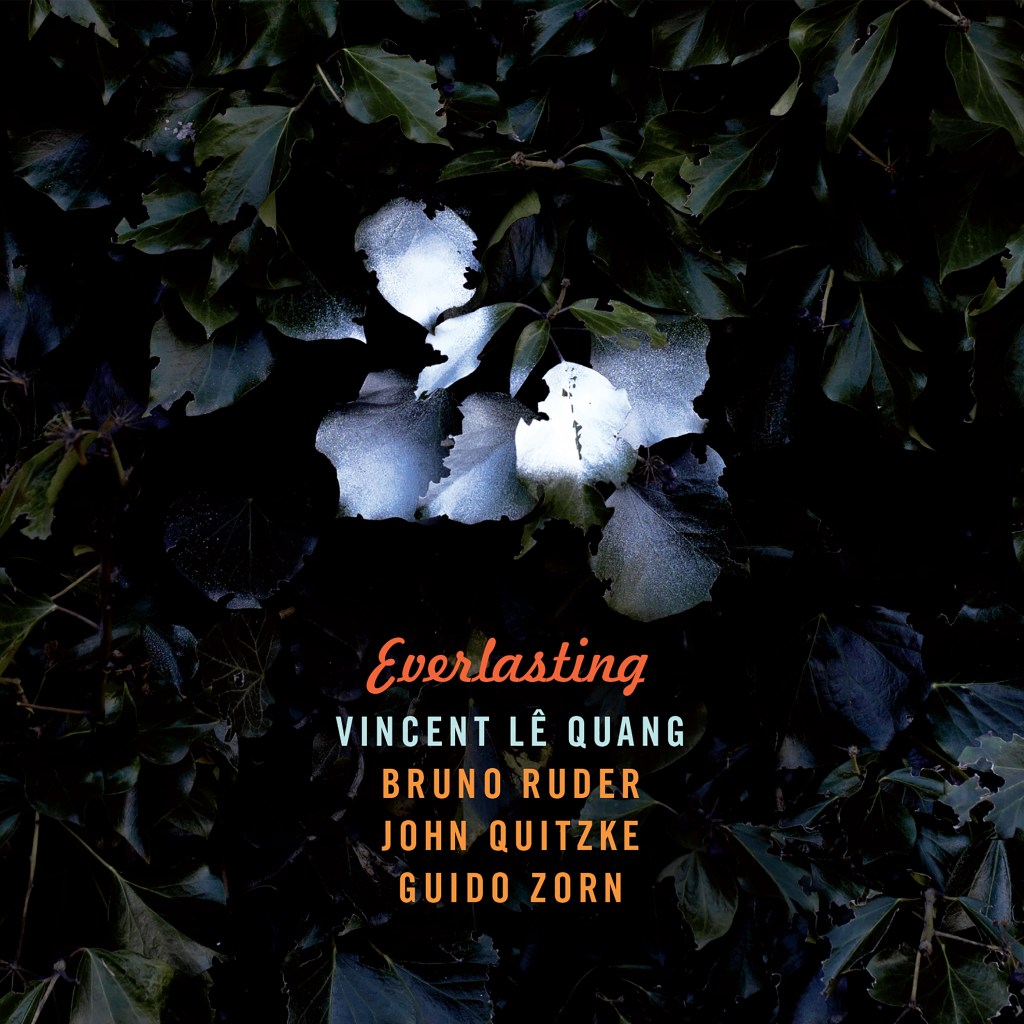

Pianist Jean-Marie Machado has long dwelled in the fertile borderlands where jazz breathes against classical form and contemporary color stains the page with new light. With his Danzas ensemble, he ventures further into that liminal space on Cantos Brujos, shaping a five-part suite that circles the incandescent heart of Manuel de Falla’s El Amor Brujo. The ballet’s haunted libretto by Gregorio Martínez Sierra, recast here in its French incarnation as L’amour sorcier, becomes less a relic than a living ember. Machado cups it in his hands and blows softly until it flares.

In this reimagining, the Arab-Andalusian and African currents swell like subterranean rivers rising to the surface. Flamenco’s sharper heelwork recedes, not erased but absorbed into a broader choreography of pulse and breath. What once occupied 25 minutes now unfolds across an hour of transformation. The suite becomes a ceremony, an incantation, a circle traced and retraced in ash and salt. Ritual, impressionist haze, and improvisational daring mingle until genre dissolves into atmosphere, a meditation on how memory mutates when sung by new mouths.

The opening gestures are hushed, almost reverent. Piano tones fall like droplets into still water while cello and viola unwind a thread of longing. From this tender aperture emerges “Canción del amor dolido,” a surge of collective breath. Percussion flickers, horns flare, and a soprano saxophone rises in a line so supple it seems to write its own script in the air. The music blooms forth, petal by petal, into “La luna y el misterio” and “En la cueva – La noche,” where shadows acquire texture. Élodie Pasquier’s clarinet in the latter moves with liquid intelligence, slipping between registers as if navigating a dream’s shifting corridors.

Then comes “Danza del terror,” where François Thuillier’s tuba prowls, its voice rich and resonant, joined by a song that feels at once ancient and immediate. Throughout, the ensemble achieves a rare equilibrium. Strength never bruises delicacy. Fragility never forfeits resolve. In “El círculo mágico,” accordion and clarinet entwine like twin serpents guarding an unseen threshold. “Magic love” glints with percussive sparkle and tensile strings, suggesting that enchantment often resides in the smallest vibration.

An atmosphere of mystery pervades the suite, yet it never drifts into abstraction for abstraction’s sake. Even at its most mystical, the music keeps one foot on soil. Many of the pieces are compact, built from cellular motifs that pulse and recombine. The clay drum and flute of “Como llamas” exchange identities with the cajón-driven “Danza ritual del fuego,” carrying us from one temporal plane to another without warning. Just as we settle into the present groove, the ground tilts and we find ourselves elsewhere, suspended between eras. It is here that passion reveals itself most vividly.

Midway through, a solo viola passage opens like a private confession whispered into a cavern. Its timbre holds both bruise and balm. “Canción del fuego fatuo” ignites with sudden joy, a firecracker sparked by a glance that lingers too long. In “Chispas brujas,” Machado converses with cellist Guillaume Martigné in phrases that seem to circle an abyss, daring gravity to claim them. The tension hums. Each note feels like a match struck in darkness.

There is also play. “Danza y canción del juego de amor” struts with buoyant assurance, the full ensemble reveling in its own amplitude. Moods link together like charms on a bracelet, each one catching light from a different angle. Voices rise and recede, tones interlock, and influences weave a tapestry that refuses hierarchy.

All paths lead to “Final – Las campanas del amanecer,” whose orchestral breadth opens the horizon as a diary left unlatched. Dawn arrives with a sound that feels almost architectural, building a world as it erases the last traces of night. The suite closes without sealing itself shut. Instead, it gestures outward, toward a space where the old story has shed its skin and the new one waits, luminous and unclaimed.

When a work rooted in one soil is transplanted and tended by different hands, what grows is neither a replica nor rebellion. It is something in between, something that speaks to the blurriness of identity and the strange fidelity of transformation. Perhaps art’s deepest magic lies there, in its refusal to remain fixed. We listen, thinking we are tracing a lineage, only to realize that lineage is tracing us, inscribing its fire in our own unguarded chambers.