John Holloway Ensemble

Henry Purcell: Fantazias

John Holloway violin

Monika Beer viola

Renate Steinmann viola

Martin Zeller violoncello

Recorded March 2015 at Radiostudio DRS, Zürich

Engineer: Stephan Schellmann

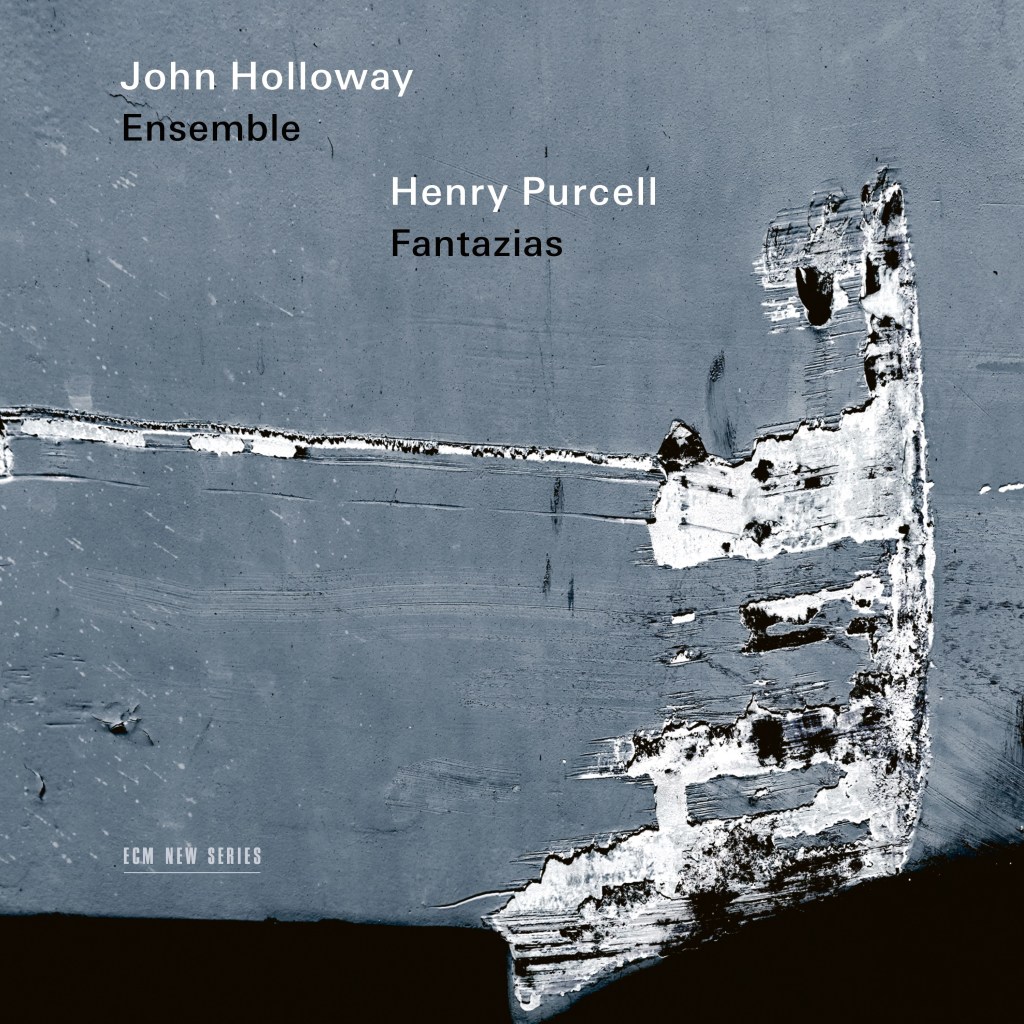

Cover photo: Thomas Wunsch

Produced by Manfred Eicher

An ECM/SRF2 Kultur coproduction

Executive producer (SRF): Roland Wächter

Release date: September 22, 2023

Henry Purcell (1659-1695), best known for his operas, was no less a formidable composer of instrumental music. His Fantazias are the pinnacle of the form, rich in their intermingling of counterpoint and polyphony. By the time Purcell put these to paper in 1680, the fantasia was over a century old. Despite being honed into a science by such estimable predecessors as William Byrd, William Lawes, John Jenkins, and Matthew Locke (whom Purcell replaced as “composer in ordinary with fee for the violin to his Majesty,” Charles II), it had fallen out of favor. Violinist John Holloway calls the present collection “a personal farewell to a kind of music, which in Purcell’s own chamber music would soon be superseded by sonatas.”

Leading an ensemble that includes violists Monika Beer and Renate Steinmann and cellist Martin Zeller, Holloway regards these 12 gems through a jeweler’s glass, cherishing every occlusion as a testament to its crafting through time. We encounter them here out of sequence, beginning with the river’s flow of No. 10. The sound is both creamy and metallic, sometimes allowing dreams to peek above the surface while at others pushing them into the mysteries of the current. Like No. 4, it affords a special sort of grace, pivoting from a seamless introduction into an intricate unfolding without changing skins. The ensemble matches with a palette that is equal parts shimmer and shadow.

Indeed, while these strings owe much of their grace to the composing, one cannot discount the players’ lifeblood. Like actors in a stage play, they embody these “characters” from within. In No. 6, for instance, Holloway’s violin laments like an agent of mourning while the others cross-hatch that inward focus with extroverted streaks of illumination. This dynamic reverses as the urgency heightens, and Holloway grabs hold of the future while the lower strings keep vigil to avoid forgetting the past. No. 9 is its companion in spirit: Even when it dances, it casts hedonism into the fire. Nos. 7 and 8 are equally wondrous in their contrasts, and their slips into dissonance reveal an improvisatory heritage, making them feel spontaneous, raw, and passionate.

In his liner notes, Holloway says, regarding the English composer’s handling of the form, that Johann Sebastian Bach “would certainly have acknowledged it as equal to his finest achievements in this art.” This is perhaps nowhere more obvious than in No. 5, the knotwork of which immediately suggests The Art of Fugue. Sitting on its right hand and left are Nos. 11 and 12. As translucent as they are viscous, they constitute a trinity of resolution that begs for more yet offers salvation only through silence.

While the above pieces are in four parts, Nos. 1-3 are in three. More intimate in form but no less expansive in scope, each is a dip into the heart of a creator whose font ran dry too soon.