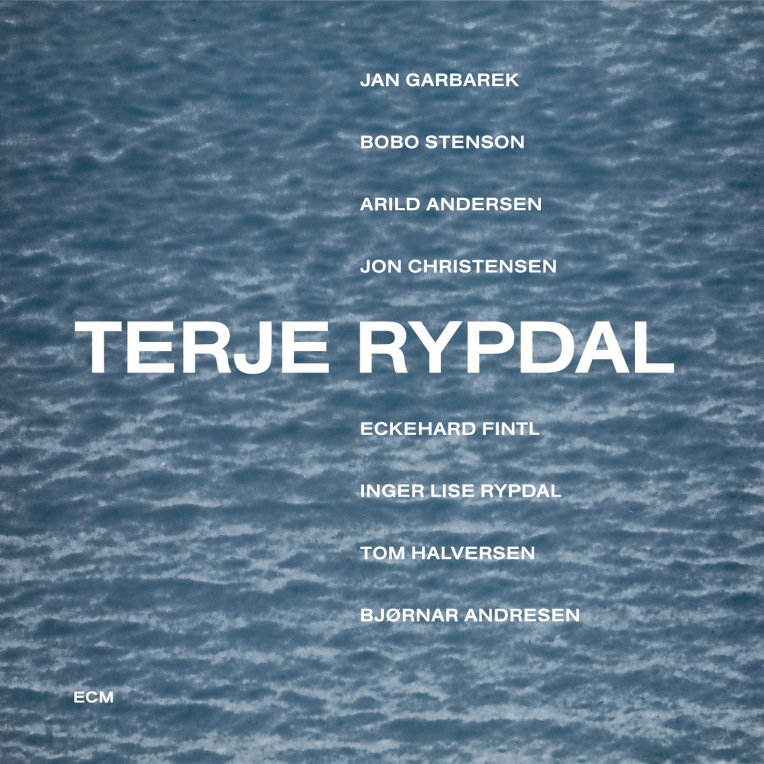

Terje Rypdal guitar, flute

Inger Lise Rypdal voice

Ekkehard Fintl oboe, English horn

Jan Garbarek tenor saxophone, flute, clarinet

Bobo Stenson electric piano

Tom Halversen electric piano

Arild Andersen electric bass, double-bass

Bjørnar Andresen electric bass

Jon Christensen percussion

Recorded August 12 & 13, 1971, Bendiksen Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Terje Rypdal’s first ECM effort as frontman is a bewitching look into the Norwegian guitarist’s formative years. With a bevy of talented musicians in tow, he forges a mercurial portrait of late-night melodies and hidden desires. “Keep It Like That – Tight” is stifling and seedy, buffeted by cooling fans and laced with the fumes of an alcoholic haze. It’s a desolate hotel room where more than evening falls, a cigarette put out on the skin, incoherent words spilling from warm lips. The atmosphere is acutely palpable, oozing with film noir charisma and slurred speech. Garbarek spins a notable solo here, only to be overtaken all too soon by Rypdal’s drunken swagger. One might think this would be a taste of things to come, but Rypdal surprises with “Rainbow,” a most ethereal track laden with reverb and stratospheric beauty, dominated by oboe for a more classical sound. The background clinks and hums with a variety of percussion, bowed electric bass, and flute. The third track, “Electric Fantasy,” lies somewhere between the first two, a jazz suite with symphonic flavor. Rypdal’s former wife Inger Lise adds some moody vocals as an English horn expands the sound even further. Illusive drumming from Christensen and the occasional wah-wah guitar add dynamic touches of their own. The ambient crawl of “Lontano II” reverses the opening effect by leading into the more blues-oriented “Tough Enough,” leaving a grittier aftertaste.

The striking differences in instrumentation between tracks may be off-putting to some, while others may see it as part of a larger concept. Either way, this self-titled album is thematically rich and more than worth the listen.

<< Jan Garbarek Quintet: Sart (ECM 1015)

>> Keith Jarrett: Facing You (ECM 1017)