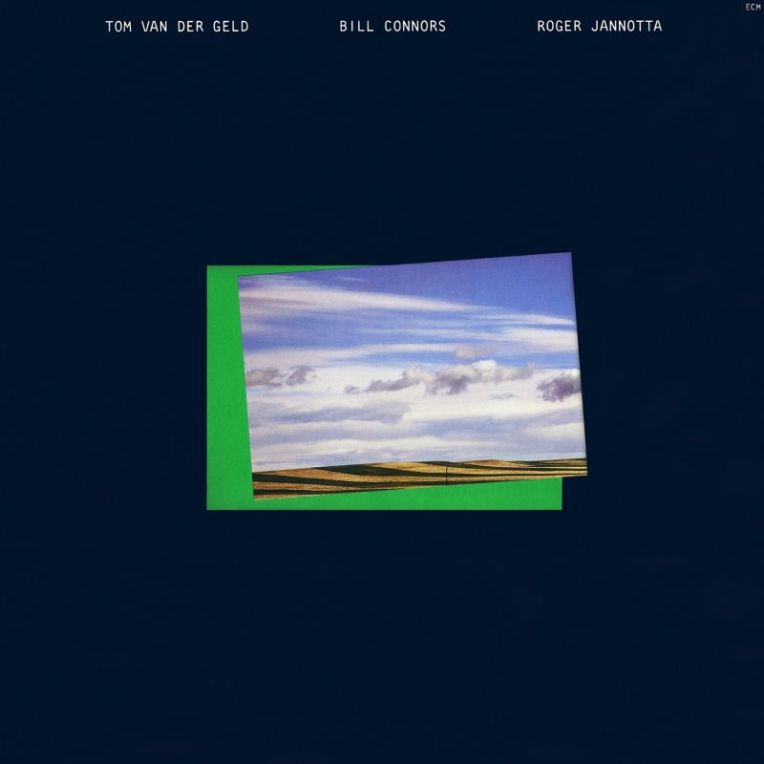

Tom van der Geld

Children At Play

Out Patients

Tom van der Geld vibraharp

Roger Jannotta tenor and alto saxophones, bass clarinet, oboe, flute, whistles

Wayne Darling bass

Bill Elgart drums, percussion

Recorded July 1980 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Steve Lake and the band

Was it you?

was it me?

who said that if

two people think the same

then one of them is unnecessary.

Well if that’s true, my friend,

I hope it’s you.

–Tom van der Geld

Vibraphonist-composer Tom van der Geld’s ECM initiation came by way of the JAPO sister label when, in 1976, the self-titled Children At Play introduced listeners to an album of uncompromising originality. Recorded in 1973, the same year of van der Geld’s permanent relocation to Germany (where the band’s reedman, Roger Jannotta, and drummer, Bill Elgart, would also find new homes), it’s a formative release not only for being Children At Play’s first, but also for sharing its uniquely sunlit sound with the world at large. Tropical and sweet, the album is a sparkling endeavor that favors the lived reality of jazz over its descriptive pitfalls. Patience (1978) was van der Geld’s first dip into ECM proper and stands out for its bright geography. This time, however, the tectonic plates shift more abstractly below with the heat of friction. The freedom of this sophomore effort offers plenty of room for the listener to find a story. On its heels came Path (1979), the phenomenal trio album with Jannotta and guitarist Bill Connors. Hewn in pastels rather than oils, it’s a decidedly softer and sometimes-haunting affair.

This brings us to 1980’s Out Patients, in which van der Geld closed the JAPO circle alongside the ever-versatile Jannotta (on tenor and alto saxophones, bass clarinet, oboe, flute, and whistles), bassist Wayne Darling, and Elgart on drums and percussion. Two of the vibraphonist’s compositions bookend the album, contrasting the free unity of “Things Have Changed” with the expressive rubato of “I Hope It’s You.” The first coheres into a loose brand of unity, the bass clarinet a noteworthy foil to van der Geld, who takes an early solo down a slippery slope yet maintains tactful balance within the rhythm section’s mosaic. The concluding tune finds Jannotta (on tenor) leading with truth. The reedman further contributes “Dreamer” for the listener’s fortunate consideration. It travels and unravels somewhere between starlight and sunrise, revealing a melodic core in Jannotta’s flute and Darling’s resonant bassing. The latter’s “Ballade Matteotti” awakens like a dawn chorus. Van der Geld describes so much of the image that, were his bandmates not so attuned, they might feel superfluous. Their ease of diction contributes to the group’s strength. Consequently, the music flips from intense to reflective at the turn of a phrase. Jannotta’s extended delivery in the second half is tour de force in the truest sense, for in it force prevails.

Yet nothing in the program surpasses Elgart’s “How Gently Sails The Moon Twixt The Arbour And The Bough (And The World Is Waiting For The Sun,” a tune as epic as its title, and one that adds some groove to the band’s loose equation. Smooth yet crisp, and brimming with a chamber jazz aesthetic, it explores a wide dynamic range, with a memorable midsection in which delicate utterances ripple through the quartet. Jannotta (now on alto) lends mystical qualities to the scene, finding scratchy-throated catharsis in the unfolding. Interpretive diffusions all around show a group becoming more unified the wilder it gets: proof that, at least in musical terms, letting go will sometimes be the key to being found.

Although Children At Play disbanded in 1981, its spirit lives on in these highly collectible recordings, as also through its leader’s commitment to jazz education. In the interest of making his mission known, below is an e-mail Q&A I conducted with van der Geld, who kindly shared his memories and thoughts. And for an exhaustive assessment of van der Geld’s career, plus a more extensive interview, check out Formosa Coweater’s fabulous article here.

Can you tell me about your musical background and about how you came to be a jazz musician?

Well, I come from a third-generation family of musicians, so I guess there is something hereditary here. I grew up in an environment where jazz was always being played or listened to. My parents had a “dance band” which played on weekends at officer’s clubs and private clubs. I played trumpet in that band for several years. Having been the world’s second worse trumpet player (!), I decided at age 21 to start playing the vibes. There was never really much of a choice regarding becoming a jazz musician. At one point, I did earn an engineering degree—mainly at the request of my father. Following that, I was devoted to music.

You seem to have followed in the footsteps of many American-born musicians who have found a musical home in Europe. Can you tell me what differentiates European approaches to jazz performance and pedagogy from their counterparts elsewhere?

The Europeans have, over the decades, developed a very special jazz signature. Significant input has come from English players like Kenny Wheeler and John Taylor. But throughout Europe there have been great players who have taken American music and blended it with their own particular cultural and musical expression. Names that come into mind would include Thomas Stanko, Jan Garbarek, Dave Holland and many more.

In the early seventies, there were very few schools in Europe with an adequate jazz curriculum. This is no longer the case. There are excellent jazz departments in many European universities.

Who did you count among your deepest musical influences when you began your professional career? Has that list changed since then?

As far as the vibes are concerned, my first influences were Lionel Hampton (the first LP I ever bought) and Milt Jackson (the first jazz concert I ever went to). When Gary Burton came to Albuquerque with his famous first quartet in 1969, I was completely blown away. Later I became one of his students at Berklee. Other important musical influences included Marion Brown, Ornette Coleman, Paul Bley, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, ESP, Archie Shepp, Eric Dolphy and Albert Ayler.

What role does teaching play in your musical life? What have you learned from your students?

I was fortunate to be able to teach and, in fact, to quite enjoy teaching. Teaching was also often the mainstay regarding things like paying the rent. And I have indeed learned very much from my students. The most important lesson: be open to questions and remain curious.

Each of the four albums you recorded for ECM/JAPO is distinct from the rest. How would you characterize their moods and styles? Is there an overarching theme that connects them all?

Those recordings are individually the result of circumstance and coincidence. There is no overarching theme connecting them. It was very rewarding to play with those great players/composers.

How has the experience of performing enhanced your understanding of jazz as an art form? Do you see jazz as an art form to begin with, or is it something else?

I don’t know: I never use the word “artist” when describing myself, and have never consciously considered these questions.

Who are you listening to these days?

Mostly piano players, with Bill Evans, John Taylor, Ahmad Jamal, Bud Powell and Art Tatum being on top of the list. I also listen often to “classical” music.

Your Ear Training textbook has enjoyed international success as a teaching tool. How did you come to write it? What did it mean for you to have Dave Liebman write its Foreword?

I had applied for a professorship at the Musikhochschule Köln (a school of music at the university level in Cologne). This must have been sometime during early 1994. Well, I didn’t get the professorship. They were, however, at that time looking for someone to teach the jazz ear-training courses. Since I had already been teaching ear-training at Berklee, they asked me to join the faculty. After a few semesters, I had produced a large amount of my own teaching materials. My subsequent method books are based on these materials.

I was extremely happy that Dave agreed to write the Foreword for these books: he is a player and teacher of great integrity for whom I have always had the greatest respect.

What is your best advice for aspiring jazz musicians?

Learn the science of our music (harmony) and develop your instrumental technique.

But NEVER forget: jazz improvisation begins and ends with your ears.

If you can’t hear it, don’t play it!