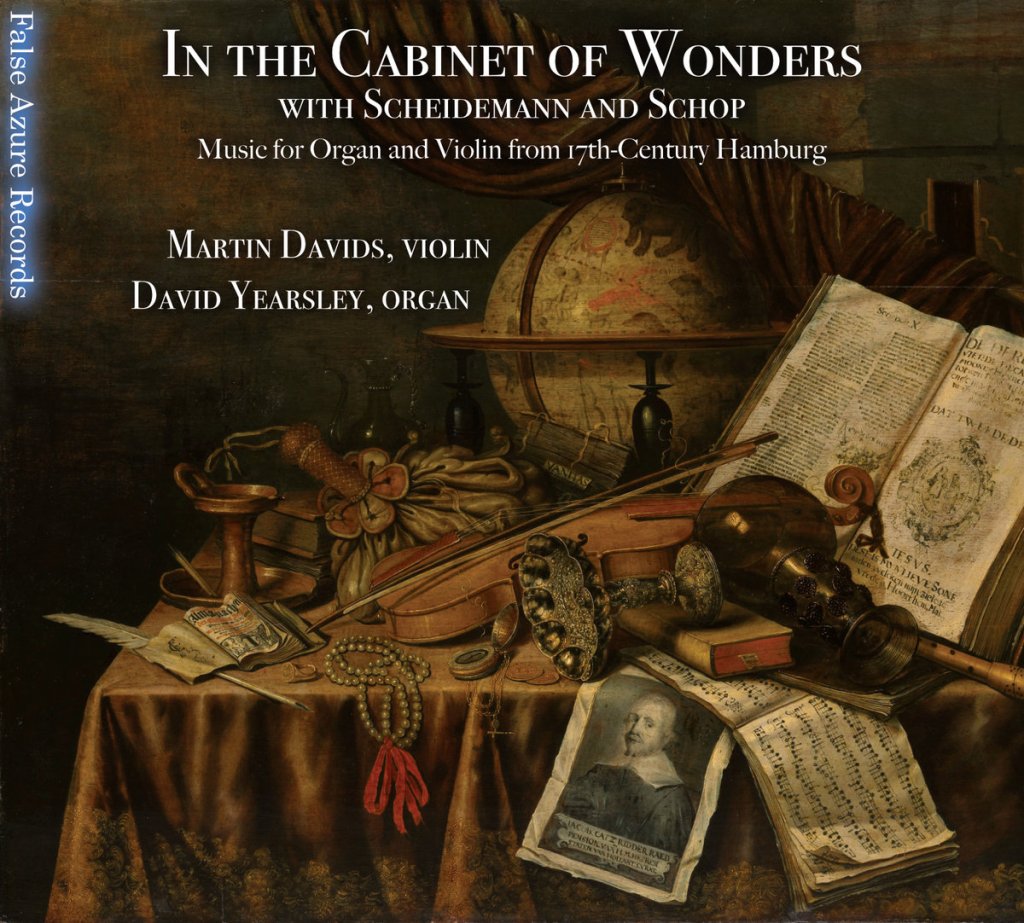

The organ is a colossus, the violin a slender voice. By sheer mass and volume, they seem destined never to agree. One threatens to drown the air in thunder, the other to disappear beneath it. And yet, in 17th-century Hamburg, they discovered a shared breath. High in the gallery of St. Catherine’s church, they spoke not as rivals but as companions, drawing crowds who came to hear scale converse with fragility. What could have been a contest was a study in equilibrium, like a skeleton learning, haltingly, how to stand upright.

It was in this bustling hub that Heinrich Scheidemann (c. 1595-1663) and Johann Schop (c. 1590–1667) met across air and string. Their sounds descended like thought itself, Scheidemann’s pipes carrying the gravity of heaven, Schop’s bow and strings tracing the precarious outline of the human voice. What emerged was more than music. It was a convergence of opposites: cleric and townsman, traveler and citizen, the enduring and the fleeting. In that reverberant space, the city heard itself briefly whole, briefly hushed, before motion returned and the pulse of everyday life resumed.

Under Scheidemann’s quick, laughing hands, sound sprang outward, ricocheting through stone and space with wit and momentum. The organ became less a monument than a body with many lungs, capable of sudden whispers as well as exuberant exhalations. Alongside this abundance, Schop’s violin did not retreat. It danced. Its lines flashed with surprise, then slipped without warning into shadow, like muscles tightening and releasing beneath the skin. Between them unfolded a living exchange, in which the church itself became a resonant demonstration that opposites, when truly listening, can cohere into a single organism.

This album invites the listener into a corporeal experience, one that breathes, sweats, remembers, and occasionally stumbles forward in exhilaration. The music of Schop and Scheidemann, as reimagined by 21st-century analogues Martin Davids and David Yearsley, circulates like blood through civic arteries, passing between church lofts, dance floors, and private chambers, rarely holding one posture for long. What binds the recording is neither style nor chronology, but a shared faith in music as something handled, inhabited, and exchanged socially. Sound is treated as anatomy rather than abstraction. What we hear are the bones of it all, flexing, testing their reach, discovering what they can bear.

Schop’s Intrada à 5 from Erster Theil newer Paduanen opens the album by wrapping the senses in gauze. The interwoven voices refuse hierarchy, relying instead on mutual dependence. Each line anticipates the others’ weight and direction, like ribs designed both to protect and expand. This is consort music already aware of its future disassembly and reconfiguration, carrying that latent plasticity within it. The partnership feels so complete that separation seems almost injurious. From the outset, beauty is not the goal but the consequence. Expression rests on marrow and sinew, and imagination requires a listener willing to inhabit the charged space between intention and realization.

Much of the album’s gravitational pull lies within the orbit of ’t Uitnemend Kabinet of 1646, where Schop’s violin resurrects itself as heir and provocateur. His reworking of Alessandro Striggio’s Nasce la pena mia unfolds like a slow-motion game of double dutch, the ropes of austerity and playfulness turning with deliberate care, demanding full coordination to avoid collapse.

The Lachrime Pavaen after John Dowland presses further inward. The soul twists into a Möbius strip of emotional transference, sorrow folding endlessly back upon itself without settling. Chromatic figures reach deep into the gut to retrieve a half-digested grief and hold it up for inspection. Yet nothing here feels morbid; instead, it suggests that emotion without physicality would simply cave in, that even pain needs a skull in which to resonate.

Scheidemann answers this inwardness with motion and propulsion. His Galliarda ex D sets fire beneath the feet, insisting on the intelligence of movement. Rarely do both touch the ground at once. The sound remains perpetually mid-step, angled toward what follows. Dance here is a matter of orientation, a way of thinking forward with the entire frame. That energy carries seamlessly into the Canzon in G, whose relaxed atmosphere allows light and shadow to exchange places with quiet charm, the organ responsive rather than domineering.

At several moments, the album reveals its improvisatory foundations. The performers’ Intonatiofunctions as connective tissue, recalling a time when much of this repertoire lived between the notes, sustained by trust, familiarity, and shared risk. This ethos extends into Scheidemann’s setting of Christ lag in Todesbanden. Told in two verses, the first establishes the firm outline of a torso, while the second pencils in the extremities.

The relationship between instruments grows aerodynamic in Scheidemann’s intabulation of Giovanni Bassani’s Dic nobis Maria. The cadence is measured yet generous, giving the violin space to breathe while the organ subtly lifts and supports. Imagined as wind and wing, the pairing becomes a lesson in controlled flight, with ornamentation serving as lift. This play of disguise reaches its height in the Englische Mascarada, where the organ steps forward alone. It imitates viols, recorders, and cornetts, its movements almost tactile. The backdrop assumes the foreground, and scale itself learns to play, shedding weight without surrendering substance.

Schop’s sine titulo from ’t Uitnemend Kabinet may be the album’s quietest act of defiance. Tone, transition, and spirit nourish one another organically, as if the piece were activating its own nervous system mid-flight. The violin’s occasional double stops flare like shooting stars across an otherwise stable sky, fleeting, unnecessary, and wholly persuasive.

As the program draws toward its close, its communal heart comes fully into view. Schop’s Præludium, the first work ever published for solo violin, clears the air with intent, a measured breath before speaking plainly. What follows, an improvisatory fantasy on his chorale tune Werde munter, mein Gemüte, unfolds as a conversation restored. The organ answers phrase by phrase, until the violin can no longer remain apart and joins the coda. Harmonies shimmer. What emerges is gratitude, rooted in shared labor. The album concludes with the Pavaen de Spanje, whose stark colors and abrupt shifts return us to orbit.

By its end, the recording has quietly redrawn the boundaries of historical performance. This is no reconstruction, but a living metabolism, a system dependent on circulation, exchange, and constant adjustment. The music does not ask to be preserved so much as inhabited. It leaves the listener with the sense of having moved through a body rather than examined an object, of having felt joints flex, lungs fill, and organs hum in sympathetic response. The final sounds do not conclude so much as release, sending us back into the world more aware of our own inner architecture, and perhaps more willing to trust it when it makes overtures to leap.

In the Cabinet of Wonders is available from False Azure Records here.