“You have to be empty before you come to a recording,

and then start again.”

–Manfred Eicher

Some opportunities connect dots that have been in our vision for too long. Others make us realize that the lines are already drawn and have merely been waiting for our souls to catch up. The latter discovery is foremost on my mind as I touch down at Munich International Airport in the heart of winter. Like the landscape that distances my eyes from the city shuttle windows, it reveals the occasional thicket of trees, airbrushed and reassuring against the gray cloud cover. I have arrived in a strangely familiar place, have crossed more than a soft language barrier to make the pilgrimage for which all these years of listening have prepared me. Munich—and, more specifically, the record label nestled so modestly within it—has called to me, and I have answered. It’s the 10th of January, 2013.

Many things have lured me here. Foremost among them is ECM: A Cultural Archaeology. The once-in-a-lifetime exhibition, on display from 23 November 2012 through 10 February 2013 at the Haus der Kunst, represents an unprecedented consolidation of resources and archival materials, and pays due homage to the label’s worldwide influence. Said influence has been funneling directly into my beating heart since, as a teenager, I first laid ears on a radio broadcast of Arvo Pärt’s Te Deum. Yet before I place even one foot through the museum door, I have a talk to attend.

The place: Ludwig Beck Record Shop in Munich’s Marienplatz, one of the last of its kind and host to a roundtable discussion between Evan Parker and journalists Steve Lake and Karl Lippegaus. Surrounded by the finest selection of jazz and classical CDs and vinyl I’ve ever come across in one location (it’s enough to make one teary-eyed in today’s digital overflow), I’m sitting among a dedicated group of admirers, whose psyches have all been touched by the English saxophonist/composer’s activities in some way or another. “It’s not just rewarding; it’s also addictive,” says Parker of improvisation, which for him is indistinguishable from composition. Before diving into a deconstruction of terms, however, he begins with a recent anecdote that finds him playing his horn as quietly as possible in his hotel room, “so as not to disturb the neighbors.” It represents a new direction for him, a way of screaming without being heard. From this image unspool ribbons of reflection on a career spanning decades, all of which gel into this figure before us, one whose groundbreaking Electro-Acoustic Ensemble has not only stood the test of time, but has practically defined time for the intricacies of its duration. ECM Records has played prism to the EAE’s light, evolving from a spindly sextet (1997’s Toward The Margins) to what is now an 18-piece fractal. The latest incarnation, he admits, sitting beside the very man who has produced the ensemble’s run for Manfred Eicher’s flagship label, boasts 47 tracks to be mixed and worked into cohesive form. While daunting in prospect, this has been the process behind every EAE record: archived bits comprise the raw material from which, through the scissors-and-paste allotments of the studio and Lake’s intuitive touch, emerge as the sonic wholes that have captivated us for the past 15 years.

Even as he is looking toward the future, Parker is looking toward the past, for tomorrow’s concert will unveil a new splinter group, a self-styled quartet that seeks to continue the spirit of his Music Improvisation Company outfit and its self-titled 1970 release, for Parker believes that the story begun with guitarist Derek Bailey, percussionist Jamie Muir, and late electronics inventor Hugh Davies in that very context was cut short. When asked about working with Davies, Parker waxes nostalgic about the earliest electronic music records, in particular the Philips “Prospective 21e Siècle” series, which from the late 1960s to the early 1970s released a distinct oeuvre in metallic sleeves and introduced household names like Pierres Henry and Schaeffer, Luc Ferrari, and François Bayle to those blessed with access. Davies was keyed into a likeminded milieu, apprenticing Karlheinz Stockhausen in Cologne during the same period (according to Parker, Davies was experimenting with circuit bending long before Reed Ghazala and his followers). His participation left a lasting mark on what would become the Parker ensemble sound, twisting the cotton candy of real-time sampling around a flexible, conical core.

For Parker, the collaborative possibilities of live electronics freshen the musical act. Taking this a step further, Lippegaus asks if Parker would characterize his music as “futuristic.” And in fact, Parker admits to being asked to produce a sci-fi film soundtrack early on in his career. This experience connected him to John Stevens (of the Spontaneous Music Ensemble) and, at a personal level, drove him beyond the Coltrane paradigm that had its clutches around so many of his generation. Parker further recalls his first viewing of the 1956 film Forbidden Planet and the profound impact its fully electronic soundtrack (cinema’s first) by Louis and Bebe Barron had on him. Regarding the use of electronics in live performance: “I can take a sample of someone looking backwards and make something that looks forwards.”

Lake asks the all-important question: What is a record for you? For an artist whose discography breaks 100, it goes from fulfillment to embarrassment within an equally wide range of production and quality. Lippegaus cites Beckett, according to whom an artist creates a “no man’s land,” an intermediary space through which s/he connects representation and reality. Is this, he asks, what Parker is doing? In response, Parker maintains that synergy between recording style and content are of vital importance (hence the nest he has found in ECM), and that regardless of whether or not the space in between is populated by flesh and bone, it must be alive with sound.

Lippegaus moves the conversation in a more central direction, citing the Transatlantic Improvisation Ensemble as an epitome of that Parker tenet: blurring the line between composition—what Paul Bley would call “paper music”—and improvisation. Similarly, Parker contends, there is much to be done in exploring the relationship between electronic and acoustic means of musical production. And just how does one put that effect into practice? The EAE’s incremental series for ECM provides a bold example, for here are sound objects whose lives have been molded from other events.

Parker can’t help but acknowledge Lake’s role in bringing out what lies within. The sounds undergo a painstaking editing process as they evolve into an organic mix that may go in any number of directions. The result is not a documentary, but a document. The latest EAE sculpture, The Moment’s Energy (2009), is closer to Parker’s dream of totally improvised pieces of symphonic proportion. Unfortunately, this dream is not economically feasible, and so the ensemble continues to stretch its vines, gathering more leaves along the way, toward overcoming that wall. Parker marvels how things are “thrown together,” a concept that will prove to be a running thread of my Munich travels and to which I return below. It’s a wonder, Parker muses, they solidify at all.

The question of economics haunts the remainder of the talk. Upon hearing what people like Parker can do, younger hopefuls are wont to ask, “Can I actually get paid for doing that?” Improvisation has become a field of employment, has even fallen under the purview of academic departments, and as such has recast a spontaneous art form as a commercial enterprise. Parker reminisces about the days when England’s welfare system was a reliable safety net for many up-and-comers to develop their art unhindered by financial considerations, whereas even some of the most respected stalwarts of the free improv scene who came to rely on that system and had no other recourse are now, despite their legendary status, struggling just to make rent. (Parker politely refuses an audience prompt to name one such musician.)

Not that any of this has stopped a new generation from crawling out of the woodwork. People will go through anything in order to have a life in this music. Hence, Parker’s repeated assertion of reward and addiction. We can hear that addiction, the drivenness of that scene, in his early collaborations with the SME (notably, 1968’s Karyobin). So just how can younger people get into this music? How does one start on the path? Parker’s answer may or may not surprise: You must know the tradition (Coltrane, Sanders, Shepp, etc.). Individuality needs community and context. This is hard to teach. One cannot break or remake the rules without first internalizing what they are. That being said, passion is the necessary spark that ignites the journey; the brain tells you what needs to be done in practical terms. You have to know where you come from, and where you’re going…not just what is. This is exactly what Memory/Vision is all about.

After hearing Parker talk at such length about the art of performance, I cannot help but ask during Q&A whether listening can also be a form of improvisation. It can, he concedes, insofar as one does it actively. The degree of participation varies with patterns of listening, which may be more rigid in classical music, for instance, than in jazz. One might think that the existence of records would put a damper in that theory, but, as Parker says, records are like calling cards. They incite invitations and new explorations, which in turn inspire more records. It’s a virtuous circle. Either way, his point is direct: We’re not going to change the history of music only by listening to it.

With such food for thought still tumbling in my brain, I introduce myself to Mr. Lake, who kindly introduces me to ECM’s Christian Stolberg in turn, before a group of us rush over to the Haus der Kunst for tonight’s concert: Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin. In an ideal musical life, I’d have been at every performance in the exhibition’s illustrious series, but all greed is tempered knowing that this will be my first. I have yet to see the exhibition proper, but because the live experience is part and parcel of it, I know that I have my hand on the door at last.

Tonight marks the Munich debut of a revamped Ronin, as regulars Nik Bärtsch (piano), Sha (bass and contrabass clarinets, alto saxophone) and Kaspar Rast (drums) are newly joined by bassist Thomy Jordi, who made his first ECM appearance with the group on Live (ECM 2302/03). In a program that culls a majority of its drama from Llyrìa (ECM 2178) and Holon (ECM 2049), this formidable foursome spins its precise web to mesmerizing effect from note the first. Those familiar with the band’s “Zen-funk” approach encounter the same logic as those hearing it for the first time: an internalized web of memory and cinematic charge polished until it slides from our grasp into a pool of code. The hip descriptor is more than just that, for it aspires to the readiness of insight that is central to Zen’s Mahayana slant, which itself upholds the universality of enlightenment. And certainly Ronin’s sound, shifting as it does from one “module” to another, realizes that same uniformity on stage through the labor of creative achievement. This despite the standout Bärtsch, who through a bass drone of dampened strings welcomes the darkness on stage before looping himself through an array of speakers and opening the portal for his disciples to follow suit. Each brings his hue to the spectrum, which for all its variety and turns of phrase engenders an inseparable oneness of purpose. The pathos of Sha’s bass clarinet is the twilight to Bärtsch’s gibbus moon. The first seamless transition into a funkier brandish early on characterizes the evening’s subsequent happenings. Thus evinced, an open tangibility breathes throughout the concert space via Bärtsch’s anatomical musings and Rast’s water-over-rocks drumming.

After this dense tessellation, Jordi’s pianistic ostinato gives our tonsured leader just the clarity he needs to overlay his fluid soulspeak. With reed popping and drums morphing, we can almost feel the watch gears of time turning on their pentatonic axes. This music would seem to paint for us an unfathomable dream, yet here it is, wrapped in tinsel and circumstantial evidence. Like waiters balancing trays of paradox, these young talents saunter forth with scents of fully cooked sounds. Alternating currents flow from their quiet wellsprings, animating a soaring solo from Sha, who has the most profound moments of the concert before the piece ends on water droplet highs from keys. Steve Reichean motives then blend and sway, as percussive record skips from Sha flicker like camera shutters of the heart. His contrabass clarinet brings a didgeridoo’s earthiness to the palette, leaving Bärtsch to break out the electric for some halation of his own.

We are treated to two encores. Amid a hatching of pauses and muted lines, the first finds Jordi cross-fading between cells, even as the band’s locomotive steam wrings the air out like a freshly washed sheet. It is the crescent as pulse, and signs off on a cloud. The second finds Ronin alive with meditative starbursts. Another transcendent solo from Sha, this time on alto, provides a limber fulcrum of connective tissue. His free jazz peaks signal a tectonic shift in the band’s sound: a node of things to come.

Ronin articulates its language with smoothest blades. Bärtsch spends much time with his hands inside the piano, revealing there a rare consistency with his live, fleshy preparations. He is in control of his vocabulary, giving theatrical vocal cues, thus guiding the vicissitudes around him to communicate with full, jigsawed diction. Those head-nodding moments of catharsis turn into windows of reflection in the brooding soil of development. Their melodies leaves deep footprints, each cushioned at a lake’s edge and washed away in the spring thaw.

Mr. Eicher and his engineers are present, and their touch is superbly felt throughout in the mixing, which after some level-adjusting in the first act brings forth a rare live experience. One can feel their aesthetic in the sound, especially through an artificially recreated reverb, applied in situ, modeled after the acoustics of Austria’s Sankt Gerold, a touchstone location for many of the label’s New Series sessions. All of which makes the stage lighting rather distracting. Aside from a lovely gush of rusty color on the curtained backdrop at one point, the visual mood is otherwise too well synchronized with the goings on to be of any value. Better for them to play with openness, if not in the shadows from which their sound is spun, and let the music bring its own illumination.

Of that openness we get plenty as the Evan Parker Electro-Acoustic Quartet takes the stage the following evening. Under naked and unchanging lights, Parker’s soprano stands at center, with percussionist and longtime ally Paul Lytton at his left, and electronicists Richard Barrett and Paul Obermayer (a.k.a. FURT) to his right. Using samples from the aforementioned Music Improvisation Company record, in addition to snippets captured and manipulated in real time, Barrett and Obermayer flood the stage from their table of laptops and accoutrements with acute matrices of feedback. The one-take burst that ensues begins as if ending with Parker throwing himself into a hall of digital mirrors. A procession of clicking tongues, hastening toward starlit expanses of crystal, bids us welcome. In order to see outside, it seems to say, we must look inside. By virtue of a circular breathing technique that is liquid mercury in the ears, Parker flips mushroom cups inside out until they bleed voices from the forest floor, leaving Lytton to bow the trees in response to their call. In the electronic window, the soprano’s inner Medusa whips her snake-tongued wishes in hopes for a mirror of her own. A stutter and a clip become the forge of Perseus’s adamantine sword, where is housed the dearest refuse of regret. Strings of things pull their backsides forward until they fly from the exhaustion of ghosted wind. Parker stops yet remains. The house continues to build itself. And in fact, some of the most visceral exchanges take place between Lytton and FURT, whose ecosystems nevertheless bubble with Parker’s past selves. He drops fly lures into these with selective care in a remarkable display of dynamic control and tasteful phrasing. Although barely a half hour long, the quartet’s statement is as full as the exhibition that awaits me the following day.

Before that, however, is the second half of tonight’s double bill: Food. Consisting of English saxophonist Iain Ballamy and Norwegian percussionist Thomas Strønen, this self-replicating duo builds one loud wall after another, and with the help of guest member Christian Fennesz’s electric guitar-driven atmospheres fleshes out the bones of what is visible. Ballamy begins the set in disguise, hiding like his cohorts behind washes of loops and alterations. Even Strønen’s clear-and-present treatments take on a distant quality as he builds on himself busily through drum machine and sampler. Washes of shoegazing from Ballamy, in combination with Fennesz’s thrumming haze, paint backdrops of vivid sunrise. The result is a sound-world that confronts rather than invites, for it has already completed the journeys of which it speaks. Between Strønen’s mountainous songs and the potent whisper of Fennesz’s warmth, there is plenty of snow-blind to squint through in order to find the wayfaring message within. Into this stream a soprano sax dives, carrying streamers of shimmer for a tail. Strønen emerges as the most prominent voice as the set grows, beginning often with a delicate snare and mallets before multi-tracking himself into outer space. Ballamy breaks out his electronic sax, if only for nostalgia’s sake, and with it catapults birds into the machinery at hand to see what sort of nests they might build.

The most effective moments are those which are, in light of the Parker experience, the least dressed up. Warped gongs paint frown lines in the corners of the stage’s smile, but betray nothing of the intense listening that flows through every moment of this carefully constructed music. The crimson tide weakens until the weakening itself turns crimson in the depths of a catacomb fire. These are the markings left behind and the ashes that feed them. Desert visions trade places with oasis fantasies as the spells crash all around us, each a quest (if not a question) for water before these travels have clothed us in their incandescent ways. Leaving aside the top-heavy sound mix, Food nevertheless brings to bear a gorgeous confluence of height, weight, and fission. In its multiplicity is a unity, gathering the strands of spontaneous creation as the fuel of a future-bound vessel.

After noshing on these sounds, I’m ready to dive into sleep before washing up on the exhibition’s shores at last.

As I sail through the entrance, I think back on Evan Parker’s comments about the miracle behind his music being “thrown together,” and further on German philosopher Martin Heidegger’s concept of Dasein (lit. “being-there”). As I understand it, Dasein is in simplest terms the marker of human existence. The very fact of being imbricates one in the grander scheme of things. Our being is thus determined by our having been “thrown” into a world that predates and will outlive us. It isn’t so much of a leap to draw a line to music here, for it is the blood of our thrownness. Heidegger’s attendant interest in the “unsayable” is also appropriate in the context of what ECM has done for the world of recorded sound; its catalogue has rendered audible many ruptures in the illusion of continuity that keeps us wrapped and warm at night. This may seem like intellectual posturing, but the fact is that musicians have already been keen to this function for centuries. Thus is music thrown into a preexistent landscape, where it shapes the landscape in return.

Such considerations indeed lurk behind the exhibition’s title, for what is archaeology if not an interest in ontological differences? Curators Okwui Enwezor and Markus Müller have likewise modeled the exhibition on ECM’s penchant for transparency, creating a “sensorial field” in which the interdisciplinarity of its sources breathes distinctly and tangibly. The artifact resounds.

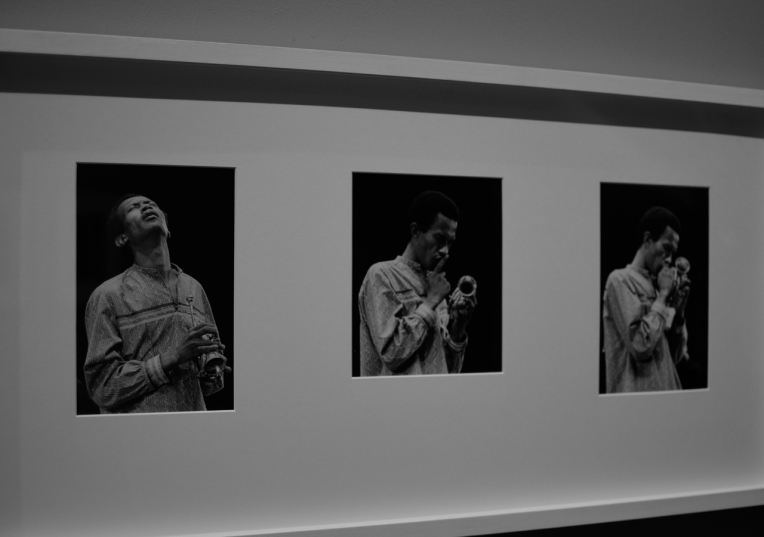

(Triptych of Don Cherry in concert at the Auditorium de Lyon, 1979, by Gérard Amsellem)

Walking into Room 1, the museumgoer first encounters a 1971 film entitled See the Music, which offers rare footage of Eicher on bass, playing with altoist Marion Brown, trumpeter Leo Smith, percussionist Fred Braceful, and Thomas Stöwsand (who, in addition to a handful of releases for sister label JAPO, produced two fine Enrico Rava sessions for ECM) on cello and bassoon.

Once believed lost, Theodor Kotulla’s vital documentary—newly restored for this exhibition and screened for the first time in over 25 years—speaks to me as if I were there. Brown’s approach to improvisation is not far from Parker’s, and the resulting mesh is as wildly dense and tantalizing as his Afternoon Of A Georgia Faun, forever one of his finest. Brown’s message echoes one that Eicher has realized in so many recordings since: namely that, in bringing together these seemingly disparate musicians, he has been able to create the music he wants to create.

The previous experiences of each feed unconsciously into the musical event set to transpire. That Eicher has carried on this ethos with full determination needs hardly be reiterated. In a characteristically honest interview, Brown intensifies my mental echoes of the Parker talk as he turns to the topic of economy. When asked about how he makes a living at this, he responds, “My ability is limited by money only.”

He goes on to say that if he could make a record every month, each would be different from the last. Considering the tip of the volcano we fortunately do have on record through this and other labels, we can only imagine what lava might have been bubbling inside him while he still breathed.

As ECM Records enters its 44th year, Room 2 reflects a calculated move on the curators’ part to focus on the first 15 years, thereby bringing us just to the cusp of the New Series, which introduced the music of Arvo Pärt, and beyond, to a wider and hungry world.

This period between 1969 and 1984 maps the label’s inception to its evolutionary need for crossover. Standing here throws me into the crux of things and alerts me to the formative contributions of what would become a familiar cast list: Keith Jarrett, Jan Garbarek, Don Cherry, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Eberhard Weber, and so many more. Six display cases house the master tapes, session photos, and original packaging of seminal albums by Keith Jarrett (The Köln Concert, Solo Concerts Bremen/Lausanne, Sun Bear Concerts),

Arvo Pärt (Tabula rasa),

the Art Ensemble of Chicago (Nice Guys, Full Force, Urban Bushmen),

(Portrait of Lester Bowie backstage in Paris, 1978, by Roberto Masotti)

and Steve Reich (Music for 18 Musicians, Octet/Music for a Large Ensemble/Violin Phase, Tehillim).

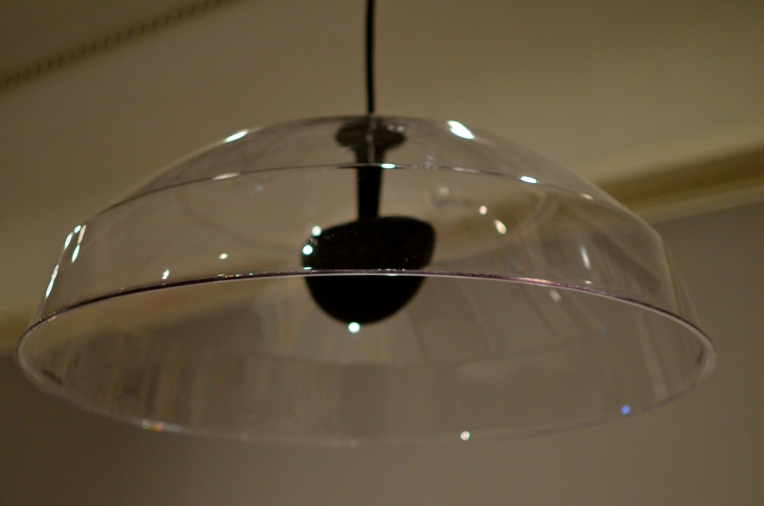

Above these displays are UFO-like domes that shower viewers with a gentle rain of the sonic past. Reich’s Music For 18 Musicians is particularly moving, floating in and out of the room as one walks about it, for it, along with the work of Meredith Monk, would plant the seeds for the imminent New Series.

Another moment of nostalgia takes me as I behold the ten-LP treasure of Jarrett’s unprecedented Sun Bear tour, at once undone and encased.

Notes Mr. Enwezor, “For ECM, music was the event, and the Sun Bear Concerts, recorded while Jarrett toured Japan in 1976, were musical events. It therefore made sense, from the standpoint of the music, to record and publish the event, economic consequences notwithstanding.”

(Portrait of Jarrett by Andreas Raggenbass)

The release of such an album speaks to the label’s unconditional empathy for its artists, which continues to speak through every polished oracle that sprouts from its soil.

Room 2 also includes two headphone-equipped television sets, both of which paint a vibrant picture of a key period and allow us to see the breadth that ECM embodied from the start. Filmed for Norwegian television in 1986, Bare Stillheten flips through the pages as they had theretofore been written and boasts enchanting footage from a Terje Rypdal “Chasers” session with bassist Bjørn Kjellemyr and drummer Audun Kleive.

(Portrait of Jarrett and Garbarek by Roberto Masotti, Zurich Jazz Festival, 1978)

The second film, Jazz 1 & 2, features more rare footage, this of Jarrett’s European Quartet with saxophonist Jan Garbarek, bassist Palle Danielsson, and drummer Jon Christensen from the mid-70s.

Long Sorrow: A Requiem for the End of Dreams, a 2005 film by Albanian filmmaker Anri Sala, is the heartbeat of Room 2.1. Through a keen ear and feeling for space, Sala indulges his penchant for charting the interstices of movement, image, and sound. From the Andrew Wyeth-like open window to a close-up of saxophonist Jemeel Moondoc in the throes of an improvisatory gaze, the camera brushes its fingers along Berlin’s underside and upends the city like a tip jar until its coins come spilling out.

By far the most immersive space is Room 3.1, which wraps one in the full soundtrack of Jean-Luc Godard’s 1990 meta-statement, Nouvelle Vague. Sitting on the plush ottoman and bathed in David Lynchean red, I find myself transmogrified, not unlike the watery dramaturgy of the film in question.

Here one can listen to images and see sound. The effect reminds me that life’s frame rate is still far beyond our technological means and sits neatly at the intersection of capture and escape. The relationship between Godard’s improvisational filmmaking and the twisted avenues of jazz is no coincidence, for it was with Nouvelle Vague that the auteur’s relationship with Eicher began.

(I leave my shadow to mark my having been here…)

Meredith Monk is the subject of Room 3.2, where a selection from Peter Greenaway’s Four American Composers (1983) offers a taped performance of the composer’s Dolmen Music.

The intimacy of Greenaway’s eye for detail is a joy to experience anew and takes me back to my first experience with his vision in The Pillow Book. Monk is well known for passing on her music orally, and what impresses me most about the film is just how clearly one can see this in the careful bodywork of her performers.

Room 3.3 is another highlight of the exhibition. The single film it houses is a veritable time capsule. Commissioned by the Haus der Kunst with the support of Project88, the Otolith Group’s New Light (a.k.a. People to be Resembling) stitches studio stills—mainly by ECM house photographer Roberto Masotti—of CODONA’s landmark ECM sessions in 1978, 1980, and 1982. Founded in 2002 by Anjalika Sagar and Kodwo Eshun, the Otolith Group incorporates countless hours of research into dense yet spacious video essays. Not unlike CODONA’s music-making, this most recent project behaves as an essay on human history, on the continuity of everyone and everything. A quote in reference to the making of audiences from Gertrude Stein’s novel The Making of Americans informs the cyclical nature of the CODONA ethos, which showed us that world music need not suffer the weight of any category before it takes flight. All of this roots itself in an anonymous percussionist’s hands at the film’s end, on which is projected the group in various stages of fortitude.

Meredith Monk returns in Room 4. It’s window: Ellis Island (1981), a once rarely seen work (now available along with Book of Days on DVD) that frames the immigrant question with an answer: to the objects of our ideological tenterhooks. In it, quotidian acts like the washing of hair convey the diurnal passage of our existence, while recurring images of tape measures and blackboards concretize the realm of objects in guise of words.

Nearby, Sounds and Silence: Travels with Manfred Eicher by Peter Guyer and Norber Widermer (2009) is also available for viewing in full.

This flowing documentary follows label icons like Dino Saluzzi (subject of the recently released El Encuentro), Anouar Brahem, Gianluigi Trovesi, Nik Bärtsch’s Ronin, and Marilyn Mazur as they flit through ECM’s hallowed studios like thoughts from brain cell to brain cell.

A most insightful experience awaits those who enter Room 5, where Stan Douglas’s 1992 installation piece, Hors-champs, offers a rare glimpse into the external diasporas of jazz’s internal languages. Featuring trombonist George Lewis, saxophonist Douglas Ewart, bassist Kent Carter, and drummer Oliver Johnson performing Albert Ayler’s four-part composition Spirit’s Rejoice (1965), the work embodies its subjects to the fullest. The title translates to “on the fringe,” and signals the assertion of critics that the free jazz it (re)presents was accessible only to white academics and bohemians. Shot at Paris’ Centre Georges Pompidou in 1992, it challenges biases with its dual-channel format, which mimics that of 1960s French television programs and allows us almost voyeuristic insight into the musicians as listeners. The period technology lends credence to the spirit of the times, and one must walk around the screen suspended in the middle of the room to gain the benefit of both perspectives.

(The screen’s edge is the lip of time)

And so, even as Johnson performs a solo…

…I must look behind him to see the others soaking it in with unadorned attention.

Through this presentation, Douglas challenges our views of television in a network dominated by dressed up realities with an unflinching integrity. The French and American national anthems referenced in the music also indicate a movement of which ECM has been at the forefront: namely, the migration of American jazz musicians to Europe.

The label’s inimitable contributions to the art of cover design and typography are on full tap in Room 6. The contributions of Barbara Wojirsch are, of course, the central theme. To see her graphic acumen in person is one of the more stirring experiences of the exhibition.

Not only are her cover images larger than I expect (a side effect of too much CD listening), but they are often multilayered and supremely tactile. So much so that I am tempted to reach out and make contact with every stroke. I can only do so with my camera.

Rooms 6.1/6.2/6.3 are the sound cabinets, each of which is equipped with high-end speakers and features an exhibition-specific playlist compiled by Eicher himself. Of these, a blood red alcove filled with the wonders of Khmer is the first to lure me inside and leaves me rejuvenated in the memory of its entry into my life.

Room 7 saves some of the videographic best for last in two documents of intense power. First is An Evening of Music and Theatre for Collin Walcott (1985). Directed by Burril Crohn, it documents a 12 May 1985 performance organized by widow Lanny Harrison Walcott at New York’s Irving Plaza. Featuring a long list of mostly ECM-related artists, including Ralph Towner, Paul McCandless, Glen Moore, Nana Vasconcelos, Don Cherry, Meredith Monk, Jack DeJohnette, Dave Holland, John Abercrombie, Pat Metheny, David Darling, Brenda Bufalino, Trilok Gurtu, Jim Pepper, Steve Gorn, Moki Cherry, Baikida Carroll, George Schultz, James Browne, and Marty Ehrlich, it cannot but inspire a heavy surge of emotions when one reflects on Walcott’s tragic death by car accident while touring in East Germany with Oregon in 1984.

This is complemented by Dororthy Darr’s Home: Charles Lloyd and Billy Higgins (2001), which captures the duo improvising at Lloyd’s Big Sur house in sessions that would become Which Way Is East (2004). Higgins shows the range of his abilities beyond the drums, playing guitar, sintir (a North African bass lute), and West African hand drums, while also exploring the idiomatic range of his own voice. It’s all the more poignant for being his final recording before illness took his life a few short months after.

Yet by far the most affect-laden part of this cultural archaeology is the multitrack tape archive in Room 2.

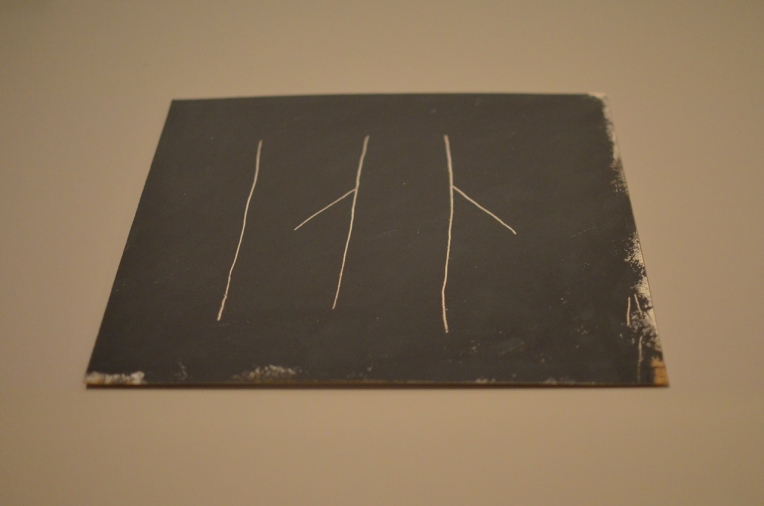

(Dieter Rehm’s 12-part Arrête la radio!, 1980, lines the wall toward the tapes)

Over 800 master tapes line the wall from floor to ceiling, chronicling the shift from analog to digital and emphasizing the undeniable materiality of the production process.

As Eicher later relates to me, it reminds us of just how gravid an enterprise it was back in the day, when producers hauled these boxes around, sometimes overseas, like the sacred objects that they were.

To stand before them is to know that silence is beauty, that in the seeming stillness of these reels there is a vibrant world waiting to leap forth into our own, and that in each there is an experience somehow catalogued and filed away. This is memory made manifest.

It also feels like a visual analogue to the sonic experience of the exhibition space as a whole, which by virtue of its relatively thin walls and close quarters enables an inevitable bleeding of sounds between rooms. Far from a distraction, it gives a real sense of the permeability of ECM’s catalogue, and feels almost like reliving the last half of my life all at once. This is an exhibition of borders, and of the mutual intelligibility of what lies on either side of them.

In this regard, Room 3 provides an exemplary juxtaposition of the visual and auditory response. One wall of this long corridor is a gallery within a gallery. Over 130 LP album covers line one wall…

…while a row of headphones opposite lures me with whispers of music that has defined me in more ways than I can quantify.

And in fact, passageways as general loci of transition enable these vestiges to sing. For every angled wall without a photograph, another, flat and secure, stands silent with history.

Such transitions abound in the final concert I’m so fortunate to attend. Tim Berne’s Snakeoil, which made its ECM debut just last year, is a phenomenal group of labyrinthine muscle and indistinguishable blends of improvisation and composition (chalk yet another full circle to Parker). Featuring its leader on alto saxophone, Oscar Noriega on clarinets, Matt Mitchell on piano, and Ches Smith on drums and percussion, the performance is quite the whirlwind on which to sign off my precious time here in Munich.

For the most part, it’s Noriega and Berne who dominate. Through a series of fractures, the two reedmen knead a heavy and conversational dough until it crisps in the fire they produce. With all this activity going on, Mitchell’s postmodern impressionism and Smith’s pointillism make for an engaging alternation of current. Berne’s first few solos of the night bore an insistent pipeline through the spine of an intervallic python, while the fantastic timekeeping from Smith—who at key points doubles on vibes—maps a wide and viscous plane. Shifting from jagged stars to gentler trapezoids at the drop of a hat, this fearless quartet takes one off-ramp after another into utterly descriptive detours. Noriega rocks the steely “Son Of Not-So-Sure,” one of a few standout brainteasers of the night. From length to style of execution, each leaves us, like another title, “Cornered” with only our minds as an out. Bustling feelings from reeds share the air with insistent chops from Smith, who at moments plays cymbals directly on the stage. As for Mitchell, he is never afraid to venture out alone, flinging handfuls of emotional baggage horizonward via masterful exercises in counterpoint. Snakeoil brings it all home with a timely Paul Motian tribute. Although it may be an encore, it feels like the beginning of something we wish had never come to an end. The skin of Snakeoil is translucent, but impervious to subversion and insular to the last flick of the fork.

In addition to the exhibition and concerts, film screenings make accessible the connections between ECM and the art of moving pictures, especially as seen through the eyes of Godard and Theo Angelopoulos. Twelve films in total reflect Eicher’s personal tastes and mirrors. Ingmar Bergman, Robert Bresson, and Andrei Tarkovsky share the bill with Gus van Sant’s Gerry (of which Arvo Pärt’s music is a leitmotif), Michael Mann’s The Insider (which draws on both Pärt and Garbarek), and Andrey Zvygagintsev’s The Return. And what better way to end than with the 1992 film Holozän. Based on the novel A Man in the Holocene by Max Frisch, it is co-directed by Eicher and Heinz Bütler, and includes music by Bach, Bartók, Shostakovich, Hindemith, Jarrett, and Garbarek.

(Carla Bley poster for Cité de la musique, 2000)

(Portrait of Nana Vasconcelos by Roberto Masotti)

As if that weren’t enough, one can leave with the massive hardbound catalogue as memento, to say nothing of the press kit—at 104 pages, a book unto itself.

As I stroll through the exhibition two days later one last time in farewell, I am eternally thankful to have been welcomed also into ECM’s headquarters, where I was invited to meet with Mr. Lake and Mr. Eicher. Sitting down with the man behind those three life-changing letters, I found in Eicher an undying excitement for aesthetic interest. He cares about his label, because the label is his life. But he is not subordinate to it. Like the title of his first production, Mal Waldron’s Free At Last, he signals an allegiance to the musical moment. When the sticks of time rub together, they will not catch if no one is there to provide oxygen. And that’s exactly what his ongoing legacy has done: like the needle to the groove, it activates the growth rings of past events as something artistic and alive.

What has always separated the music of ECM from the rest is its internality. Every album is a pill that one must swallow to know its motives. Still, the label’s external connection to art is far from arbitrary, for by virtue of being an Edition of Contemporary Music it folds itself into the everyday. Eicher is as much a film director in the studio as he is a musician behind the camera. I have now witnessed this firsthand in his direction of live performances, and feel it still as the reality of departure hits me.

Rather than mourn the separation, I bow to Eicher’s words: “Better not to conclude. The work goes on.”

Sharing your experience is a true gift – thank you very much for your words, images, and feelings. I’ve read it once, but only for the first time – like the music on the label, there is much to absorb, and it will take time.

Thanks as always, Craig. I hope it’s not too long, but I felt I had to do justice to every detail, if only for the sake of those who will never get to go there. It was a true privilege.

I live in Germany but can’t travel to see the exchibition because Munich is too far from my hometown to travel to…. but your essay made up for it and gave a VERY good impression of what to expect….What about the “A Cultural Archaeology —

Edited by Okwui Enwezor and Markus Müller” book that ECM published to go with the exhibition ? Have you bought it and can you recommend it ? I still try to decide if I’d order one copy for myself ! 😀

Yes, I bought the book at the museum shop, and I can honestly say it is a must-have for any ECM fan, especially if you cannot make it to the exhibition. Be aware there are both German and English editions. I believe the book is destined to become another collector’s item, like Sleeves of Desire and Horizons Touched, so get it while you can!

You convinced me — I just placed an order of the book ! 😀

Thank you so much for this article, Tyran. Trapped west of the Atlantic, I cannot travel to see this installation, though as a fan I desperately wish to. It is a great service you have performed; on behalf of others who likewise cannot visit Munich, many many thanks.

Thanks for this Tyran. Terrific piece you’ve written. I wish I’d been able to visit the exhibition myself but this is the next best thing. I did order the catalog which is a wonderful document. Likewise I am lucky enough to have the opportunity to see some ECM artists in the coming months. Steve Kuhn will be here in Seattle Feb. 21 and I bought tickets yesterday for Keith Jarrett & the trio July 7 in Perugia. Though the full program is yet to be announced for Umbria Jazz 2013 Enrico Rava, Paolu Fresu & Jan Garbarek are set to appear and I believe Steve Swallow/Carla Bley are scheduled as well. Keep up the excellent work. This is a remarkable resource you’ve created.

Don’t know if you saw this:

http://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/30/arts/design/ecm-album-covers-by-manfred-eicher.html?_r=0

Nice work Tyran! For those unable to attend the exhibition, you’ve certainly provided a terrific blow-by-blow. Having been at the exhibition myself back in December (and covering it for All About Jazz), this was a terrific reminder of my own couple of days spent in Munich – like you, a pilgrimage of sorts. Keep up the good work, and thanks for reaching out to me. To be continued, most definitely 🙂

A lot to take in here Tyran! The Beckett quote is interesting and I can see that in relation to my own work, creating in a space between representation and reality. Your Heidegger comments follow on too and give further food for thought.

I have heard and enjoyed Evan Parker’s music a number of times but only in small scale or even solo gigs. The whole economics of jazz performance have always intrigued me, having often been in an audience of a handful of people, even outnumbered by the musicians sometimes! The more experimentally improvisational strand of jazz (the squeakers as we irreverently refer to them) means big names can be seen in intimate circumstances for next to nothing in this country even now.

The exhibition really is a visual and aural archive excavated for those fortunate to enter. I think it really needs to be experienced in actuality but you give a wonderful (and welcomely comprehensive) evocation of the experience for those of us unable to be there. The whole approach and appearance of it seems totally in keeping with the ECM ethos of course! I am so glad you were able to make the pilgrimage and immerse yourself so fully in something so vital to your life.

Munich radio station Bayern 2 has broadcasted a two hour long programme with Manfred Eicher and Okwui Enwezor to discuss the recent exhibition at “Haus der Kunst”. The programme — with interview parts mainly in english with german translation — has now been made available as a podcast http://www.br.de/radio/bayern2/sendungen/radiojazznacht/radiojazznacht-extra-podcast-100.html