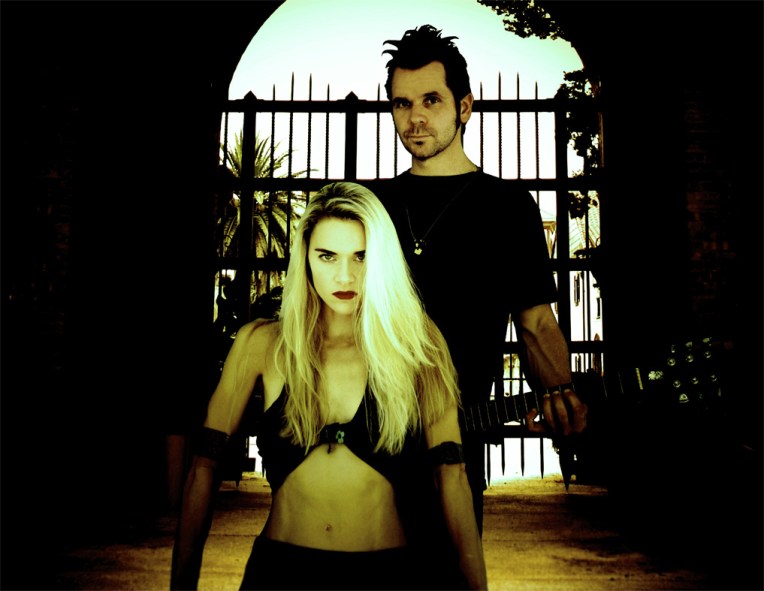

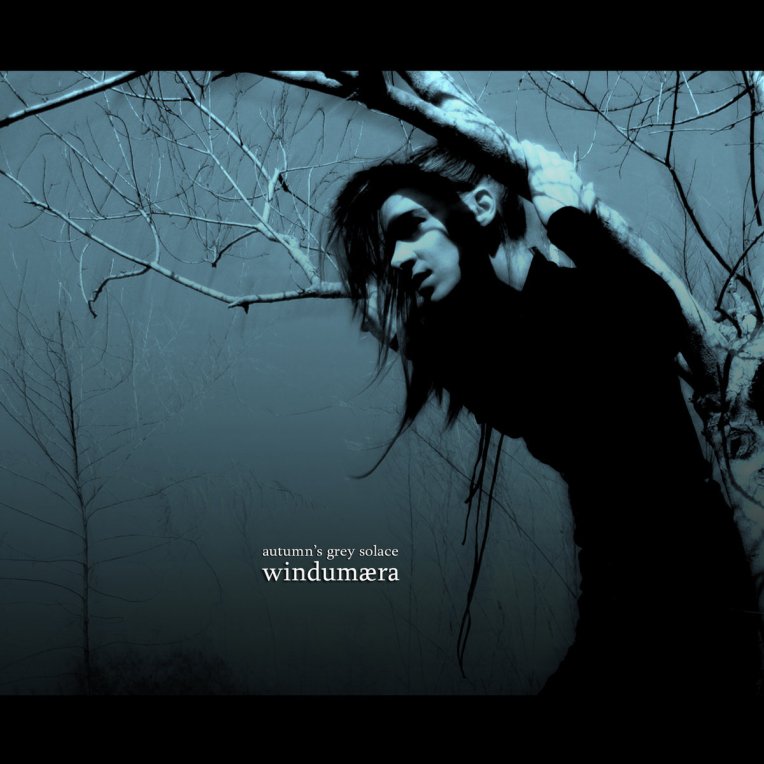

Since the release of Within The Depths Of A Darkened Forest in 2002, vocalist Erin Welton and multi-instrumentalist Scott Ferrell have been conjuring some of the most ethereal spells in the history of the craft. As Autumn’s Grey Solace, they hang notes from immense rafters, each a stage light that knows exactly where, and at what level of intensity, to illuminate the listener’s soul. Over the years, the duo has charted a trajectory of pivot-points, emerging from that ancestral forest into the brighter futures of 2006’s Shades Of Grey and 2008’s Ablaze. In 2011, at the height of their association with Projekt Records, Welton and Ferrell transitioned into Eifelian, which Ferrell tells me marked the beginning of a change in the band that crystallized in Divinian the following year and in Monajjfyllen thereafter. While the earlier albums constituted self-contained worlds, the latter two feel like a new skeleton fleshed by their self-released latest, Windumæra.

Exploring the music of AGS is like awakening yourself to beauties you never knew slumbered inside you. At the center of this galaxy is a gathering of light by which is obliterated your darkest fears. It’s a visceral, celestial body that thrives on language, melody, and the generative force of which we all partake in being born. Such metaphors are more than the hyperbole of this longtime listener, reflected as they are in the band’s approach to songwriting. It’s easy, for example, to detect a Cocteau Twins influence in their sound, and see the ways in which the duo has nurtured it to bear hybrid fruits. But less obvious inspirations lurk beyond it. “We are also influenced by some of the popular music of a period of time from the late sixties to the late eighties,” says Ferrell. “There was a time when pleasant sounding music was actually popular, unlike the last couple of decades.” We might take this to mean either that AGS is returning to some nostalgic origin story or enhancing a neglected musical turn in humble service of a new one. Whichever way we choose to interpret their sound, its purpose is clearly to connect, not alienate.

And so, while it would be easy to see Windumæra as a highly original clarification of the Cocteau Twins ethos, it draws just as much from music that has yet to be written, of which we are granted prophetic glimpses. The album’s name connotes “echoing” in Anglo-Saxon, a language featuring heavily in the song titles. “It’s a dead language,” says Ferrell of the Anglo-Saxon choice, “poetic and intriguing.” Dead though it may be, it lives vividly throughout Windumæra.

As Welton’s voice shines through the title song’s channels like sun through mist-kissed foliage, it navigates by an internal moonlight for which it requires only the star of Ferrell’s sensitive arrangement to glow. Ardent fans and newcomers alike will appreciate the height of Welton’s voice in relation to the patchwork of guitars below. She is an overseer, an eagle from whose mouth falls water and flora for an arid world. As in the album’s final benediction, the hymenopteran “Ymbe,” she evokes wings and honeyed consciousness.

Lyrically speaking, AGS has always balanced the prosaic and the poetic, but here strengthens that contrast, and thereby its invitation to indulge in the nuances of circumstance. In this respect, and beyond those connections listed above, I would venture to say the duo shares far more in common with the troubadours of the European Renaissance, plying their sonic trade across a continent that, while familiar, nevertheless pulls us into unimaginable new oceans.

Hence my confusion over AGS being so often misperceived as a “goth” outfit (in the most stereotypical sense, I mean), when in fact they seem as far a cry as one can get from the connotations of morbidity such a term may imply. For me, their music has always been a positively life-affirming search for beauty. Ferrell agrees: “We don’t associate our music with evil at all. Our mission is to create something beautiful and to console ourselves and others with music.” And if anything, consolation is at the very heart of Windumæra. We hear it in the pulsing bass line of “Sláhhyll,” which finds Welton delivering personal wisdoms as if they were materia in need of an alchemist. The synth-guitar arpeggios of “Belle” take shape just as clearly, if only more architecturally, as if inside a clock tower whose every strike purges us of a traumatic memory. Even the more subterranean tunes like “Asundran” open themselves as books in hopes of being read. As ever, Welton displays an uncanny ability to rise above her surroundings with acuity, turning hardship into ecstasy and filament.

This feeling of willful metamorphosis is perhaps the album’s central message. When I ask Ferrell about it, he says, “I like for each listener to interpret it in their own way but I would say this album has themes of freedom, expression, energy, and beauty.” With sometimes so little to hold on to in this expanse, I also wonder whether they compose their songs based on direct experiences, as part of a fantasy world, or both. Ferrell’s answer: “When I compose music, it’s way out there in a fantasy world. Erin’s vocals tend to be a combination of experiences and imagination.” Within this triangulation, it’s all the listener can do to draw a reliable map, because one wants to take into account every blade of grass and pebble. The healing energies of “Swíþfram” extend that triangle into a prism.

Because this album so deeply rewards the subjective mind, I uphold “Axa” as its pinnacle. It is a touch of vapor, a walk over rainbow bridges from solitude into communion with nature. Named after a river and meant to evoke its flowing currents, the song came together in the studio as it was being written. In contrast to “Hærfestwæta,” the autumnal associations of which recall the band’s name, it turns the ice of a painful experience into the liquid of transcending it.

Every moment of this music stems a place of genuine love, gratitude, and respect, a reflection of the souls that have found each other in this populous world to sing. The personal cocoon spun around the music is what makes it such a privilege to know. We might gaze at photos or watch videos, but until we close our eyes to the practical human concerns of their creation, these songs will not truly speak to us. They are to be embraced on their own terms, as if each were a finite entity in an infinite continuum. All of this shows in the gratitude from which they arise.

Windumæra finds AGS at the cusp of something deeper and more significant than anything the band has ever forged. It has superseded skin, flesh, and bone and placed a fingertip on the rhythms of a less tangible heart. Still, Ferrell sees yet another change on the horizon: “I think it’s the final album of the style we’ve been exploring on the last few albums and we’ll be drifting into new territory in the future.” Wherever that territory may be waiting, it has been a sublime comfort to listen to AGS’s evolution, and to know that there is still an era’s worth of moon nocturnal to be drunk in potions of expectation.

(For more information on this and other Autumn’s Grey Solace albums, please visit the band’s website here.)