Arvo Pärt

Adam’s Lament

Latvian Radio Choir

Sinfonietta Riga

Vox Clamantis

Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir

Tallinn Chamber Orchestra

Tõnu Kaljuste conductor

Recorded November 2011 at Niguliste Church in Tallinn by Peter Laenger and Stephan Schellmann, except for Estonian Lullby and Christmas Lullaby, recorded May 2007 by Margo Kõlar

Mixed at Rainbow Studio in Oslo by Arvo Pärt and Manfred Eicher with Jan Erik Kongshaug (engineer)

Produced by Manfred Eicher

“The text is independent of us; it awaits us. Everyone needs his own time to come to it. The encounter occurs when the text is no longer treated as literature or artwork, but as reference point or model.”

If the above is any indication, Arvo Pärt is one who understands text for what it is: a stepping-stone. With an attention equaled perhaps only by Alexander Knaifel, he holds words like votive candles, giving them flame by the touch of his gift for sound. Whatever we bring along the way is welcomed as it is, broken and hungry for a voice to lift its spirits. To this end, the writings of Saint Silouan (1866-1938) again form the touchstone for a program shaped as much by lips and tongue as by the Holy Spirit that guides them. If we never forget Silouans Song, the strains of which bled through the Estonian composer’s groundbreaking Te Deum recording of 1993 with especial scintillation, it is because its source had already been surpassed by the first draw of a bow. On Adam’s Lament, texts come to us as travelers with distant knowledge in their satchels. For ECM’s thirteenth program devoted to his art, Pärt builds on the tintinnabulation that shrouded his work of the eighties and nineties. He looks even more internally, seeking not only the echo’s path but also its unknowable spark.

Paradise as Adam knew it may be lost, but in the eponymous piece we find our own. Though it is an illusion made possible by reverberation and microphones, its power rings beyond the circumscription of its capture. Here, Pärt works from the inside out, finding in every contour of its ecclesial Slavic text a vision of flesh and nature. Holding these together is the touch of one whose own humility exceeds him. And is not humility the greatest mystery to be enhanced through the act of putting pen to staves? It is, says Pärt, an enigma to the stained mind: “like marble, its beauty radiates from its depths.” The locus of that beauty takes form through the body’s destruction. Even then, its reality is partial. To be sure, the gaze of science goes far in this regard but stops at the threshold of something invisible. In the absence of eyes to see, the Lord’s grace gives us receptacles to hear.

Pärt’s microscopic approach sees us as something more than the sum of our parts. Shouldering the vagaries of time, we drag our feet toward a light on the horizon. Its name is stillness, and we are its destroyers. Strings and voices do not so much blend as talk with one another, finding synchronicity through varying degrees of unrest. Paradise, then, lives on as an idea of its former self. And perhaps it was never anything more. It was the voice of generative silence. Only through its fall—which looms wispily at best in the violins—can we look back to our infancy.

Adam’s Lament is about lineages: of us as descendants of Adam, of our future as reflection of the decisions we make today, of that single thread still being spun from the breath of its Creator. As the newest of the present recording, it looks back on a singular catalogue of sonic truth-seeking and self-reflection. The handful of older pieces reworked thereafter shine like the inner circle of its rosette.

My soul wearies for the Lord, and I seek Him in tears.

“The feathery lightness of Beatus Petronius and, by contrast, the potency of Statuit ei Dominus are two sonic worlds,” says Pärt, “like the two sides of God, which I tried to touch, to trace in these works.” Composed in 1990 and revised in 2011, both embody the architectural wonders of their service. In offering themselves so directly, they take off their masks of freedom in search of the real thing. Their departure balances on the apex of a steeple, poised for the coming of sun and moon. In their brevity lies the secret to faith: never waste your words. Every syllable becomes a community in and of itself, bustling with activity in trade with those around it.

The Lord made to him a covenant of peace…

The composer imagines his Salve Regina (2001/2011) as a funnel, turning in progressively smaller circles until its center manifests like a dwarfed star. That he manages to evoke such cosmic brilliance in earthly terms is barely short of the miracle it so ardently expresses. It draws lines from cloud to soil in ways that transcend all obstacles. Starlight trades footprints with human history, filling each with enough hope to light the way in darkest night. Astonishment comes nowhere near to describing its effect.

To thee do we send up our sighs…

The Alleluja-Tropus (2008/2010) sets liturgical words devoted to St. Nicholas of Myra (270-345), whose relics absorbed its first performance in Bari. The refrain is key to this jagged string game of antiphony. Although short in scope, its feathers engage in a spectral bit of play as they float free of their bones toward skies clouded by ash and fear.

A rule of faith and a model of meekness…

L’Abbé Agathon (2004/2008) tells the story of St. Agathon, whose carrying of a leper—later, it turns out, a testing angel—is evoked in the music’s heavy gait toward awareness. A soprano of infirmity spills like ink across the baritone’s selfless paper. The resulting patterns are what the strings fill in. Like onlookers to moral awareness, they take in what is before them, realizing only later the folly of their inaction.

“For mercy’s sake, take me forth with you.”

The Estonian and Christmas lullabies (2002/2006) are, according to their composer, “for adults and for the child within every one of us.” Both arise as if of their own volition. The use of pause and reflection is genius, allowing us to bask in the delicacy of a border-crossing nostalgia while adding to it the lessons of our lives.

And she brought forth her firstborn son…

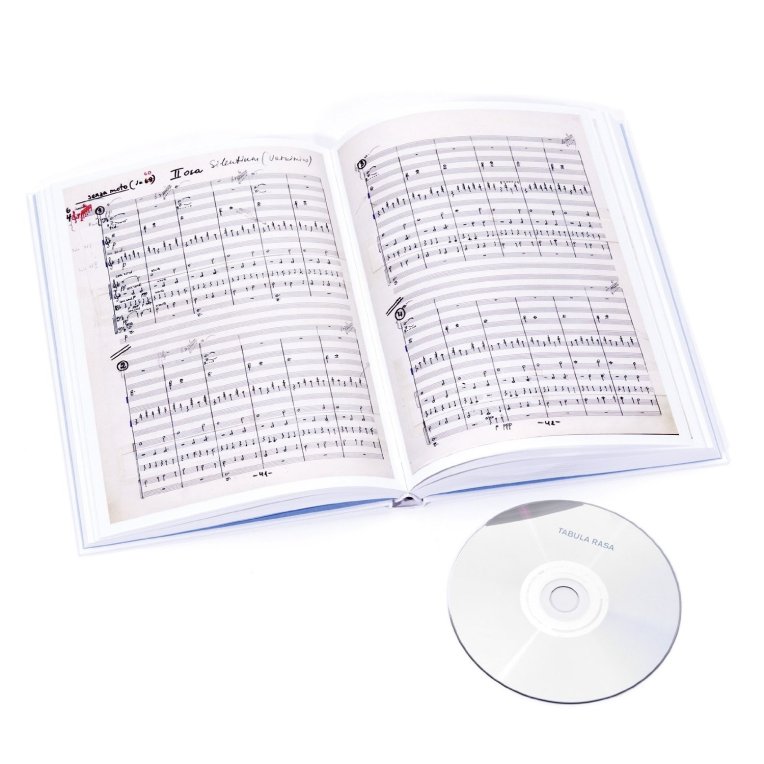

If Tabula rasa was a revelation and Te Deum a call to harmony, then Adam’s Lament is the birth of our Messiah, wrapped in Christ child’s swaddle. The association sets me to marvel at my own firstborn sleeping next to me as I attempt to recast this music into meager sentences, to seek in his contented face the promise of a time when the world will no longer hold a knife to its own throat. The manger smells of song, and its name is Love.

(My 2-month-old son basking in the warmth of Christmas Lullaby)

All of this puts a finger on the pulse of a divinity beyond the prescription of any religion, which necessarily flows in opposing directions as an embodiment of universal balance. Were it not for the bleakness of our transgressions, such music might never find our hearts, but simply flow through them, unnoticed, as part of the hum of Time. That it comes to us so undeniably is due to many talents, including engineers and producers. Yet we must thank above all Tõnu Kaljuste and the musicians at his cue. Their undying commitment to Pärt’s mission has yielded one of the most indomitable partnerships in music, classical or otherwise. One hardly needs to reiterate the fact that, as with every label project, Pärt participated fully in all stages of this production. His contact is palpable in what we hear, reaching for us like a grandfather we never knew we had and whispering a story into our souls. Much of that story has already been written. The rest is for us to inscribe.

(To hear samples of Adam’s Lament, click here.)