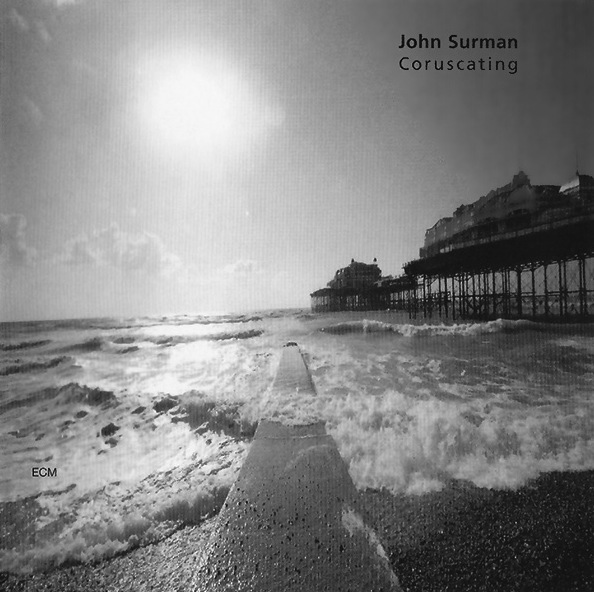

John Surman

Coruscating

John Surman soprano and baritone saxophones, bass and contrabass clarinets

Chris Laurence double-bass

Rita Manning violin

Keith Pascoe violin

Bill Hawkes viola

Nick Cooper cello

Recorded January 1999 at CTS Studios, London

Engineer: Markus Heiland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

The title of John Surman’s Coruscating means sparkling. Yet with track names like “At Dusk,” “Moonless Midnight,” and “An Illusive Shadow,” we are squarely in a nocturnal realm. The multi-reedist, along with bassist Chris Laurence, puts his touch on this set of eight compositions, which over the album’s course blend into a seamless whole. At their center is an ad hoc string quartet, to which Surman and Laurence act as improvisatory satellites. The two aforementioned sections drop Surman’s oboe-like soprano into pre-written cuts of land, each a ripple in a lake that holds ebony sky in its cup.

Although it will not be surprising to any Surman fan, it is as baritonist—ever the rightful successor to Gerry Mulligan—that he comes closest to bringing the shine. Whether in the softly rolling sentiments of “Dark Corners” or the muscular stirrings of “Stone Flower” (in memory of another baritone great, Harry Carney), his low reed dots the compass many times over through charcoal travels. “Winding Passages” is the most mature of these breeze-swept soliloquies and provides a solid platform for the composer’s bronzed hieroglyphs. Laurence shakes his most geometric ghosts out in “Crystal Walls,” while “For The Moment” mixes cello tracings into vibraphone, Surman’s restless gestures carrying us all the while into deeper pasture.

Those who weren’t quite feeling Proverbs and Songs might find Coruscating more accessible, if only because there is so much space for listeners to relax and, in spite of all the darkness, feel their way around. It is a dream of quotidian objects sleepwalking for want of a place to have purpose, only to discover that their wandering is that very thing.

<< Jan Garbarek/The Hilliard Ensemble: Mnemosyne (ECM 1700/01 NS)

>> Gianluigi Trovesi/Gianni Coscia: In cerca di cibo (ECM 1703)