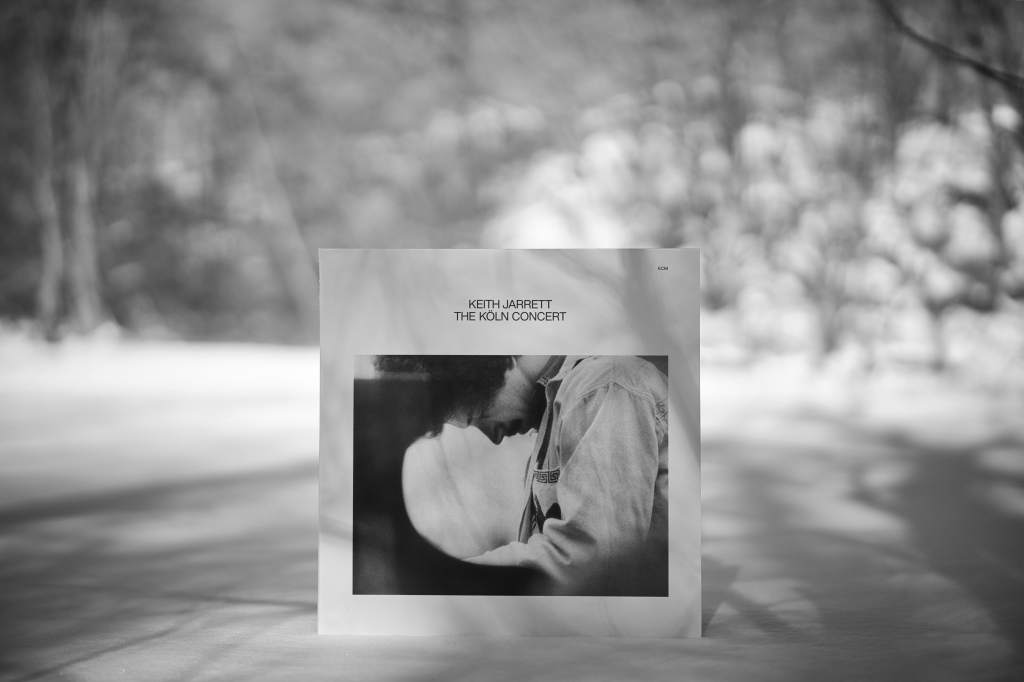

On December 12, 2025, ECM released a 50th anniversary edition of pianist Keith Jarrett’s The Köln Concert, returning one of the most unlikely landmarks in recorded music to the present age. Half a century after its first appearance in 1975, the recording remains the best-selling solo piano album in history and a resilient beacon within the ECM catalogue, an improvisation captured under circumstances so fragile that its survival feels almost miraculous. But the deeper significance of the reissue lies elsewhere. It invites listeners back to the site of a transformation. What once seemed like a fleeting document of a single evening now feels closer to a permanent warm front in the cultural atmosphere. The music continues to circulate through time, condensing into private revelations whenever someone lowers the needle or presses play.

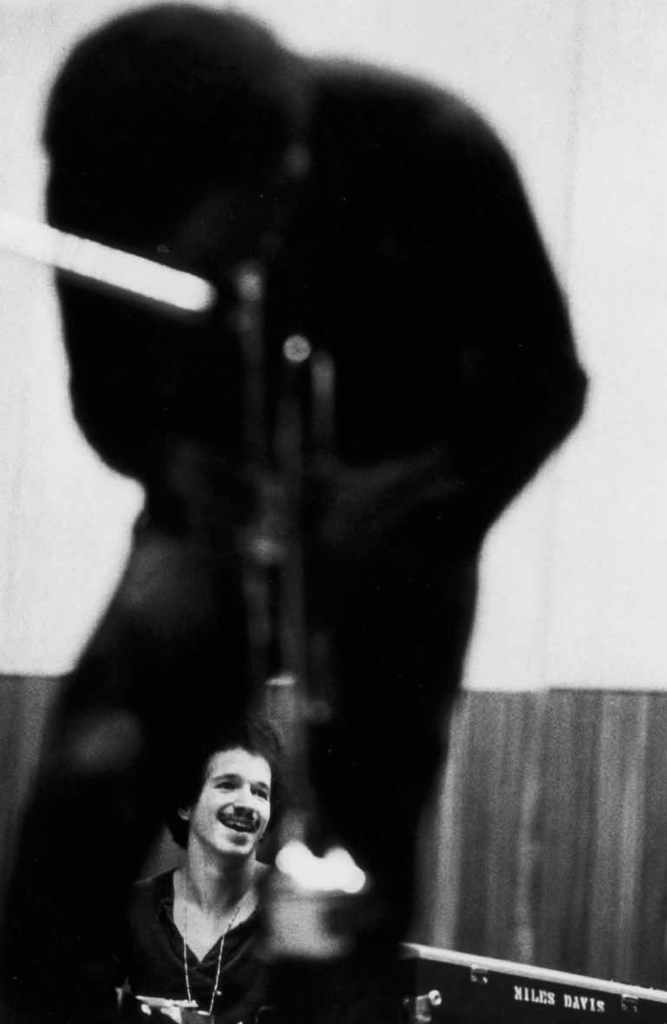

The legend surrounding the performance is familiar. Jarrett arrived in Cologne exhausted from touring. The piano provided for the concert was smaller than expected and in poor condition, with weak bass notes and uneven action. The hour was late. But the constraints became an engine. Jarrett reshaped his approach in response to these limitations, leaning toward the middle register, carving rhythmic patterns that could carry the music forward without relying on the instrument’s wounded depths. What followed, then, was a sustained act of adaptation, a musician turning difficulty into propulsion. The result has since become one of the most widely heard recordings in jazz, classical crossover, and improvised music, though it belongs comfortably to none of those categories.

In a new essay for the edition, German journalist Thomas Steinfeld recalls how there was little to distinguish the concerts surrounding the famed Köln performance and that all of them were “an expression of a will toward aesthetic emancipation.” United under that humble, if not humbling, banner was Jarrett’s commitment to improvised-only concerts, which allowed for the fullness of nothingness to make itself heard in real time. Each evening began with an empty field and ended with a configuration that had not existed before the first note. And yet, what emerged in the confines of the Cologne Opera House on that fateful date of January 24, 1975 seemed to cut out a new eyehole in the mask of history through which a new perspective on what was achievable at the piano was revealed in a way that perhaps no musician has before or since.

Steinfeld is quick to caution us against the gravitational pull of myth. This concert was one night within a longer tour and within a longer life of music. To isolate it too completely risks freezing Jarrett in a single pose, as though the artist were merely the vessel for this one improbable event. In truth, the Köln performance was a turning point along a broader arc that led to the monumental Sun Bear Concerts, whose vast landscapes of improvisation would extend Jarrett’s language even further. What we hear in Cologne is therefore not a conclusion but a threshold, the moment when one door swings open and the wind of possibility pours through.

There is something timeless about this music precisely because it is so firmly entrenched in time, documented on tape but composed in air. The opening of Part I arrives already in motion, like a river glimpsed from a bridge rather than a spring discovered at its source. Phrases rise and fall with the tentative confidence of a bird learning the currents of the sky. The melody circles overhead, close enough that its shadow passes over us. Jarrett’s left hand begins with the quiet determination of a traveler testing unfamiliar ground. A rhythm forms beneath the surface, hesitant at first, then increasingly sure of its own footsteps.

Before long, the music finds a pulse that seems older than the instrument itself. The piano becomes a breathing creature. Harmonic light flickers across the surface while deeper currents move beneath. When the famous vamp emerges just after the seven-minute mark, it feels like a clearing in the forest where everything suddenly gathers.

Yet any sense of grandeur refuses to settle into monumentality. Jarrett dismantles the structure almost as soon as it rises, examining it from within, turning it gently in the light like an object whose inner workings remain mysterious. The music behaves as a living cell. We witness its movement, its expansion, its ability to replicate feeling from one listener to another. Its mechanisms remain hidden. The effect spreads nonetheless.

The expansive final passage of Part I, with its thick block chords and surging textures, greets the listener not as a goodbye but as a hello.

Part IIa begins with a different temperament. What began as an aerial survey of the imagination now feels grounded in the body. A rhythmic pattern settles in with irresistible buoyancy. One hears the echo of gospel, the sway of folk dance, the bright elasticity of American vernacular music filtering through Jarrett’s internal vocabulary. The audience’s energy becomes part of the current. The music dances, stumbles briefly into contemplation, then rises again with renewed vitality.

This trajectory feels inevitable, as though following a path that had always existed beneath the floorboards of the hall. The music quiets into reflection before lifting itself once more with a blues-tinged warmth. Jarrett’s playing here carries the sensation of a traveler pausing beside a river before continuing onward.

Part IIb deepens the inward pull. The left hand coils into a spiraling figure that suggests a single direction of travel. Not outward but inward. Each repetition tightens the circle until the music finds an opening at its center. From there it rises into a fierce, sunlit expanse. The harmony burns with an almost desert brightness. One senses the pianist squinting into that light, moving forward despite the glare.

Such bravery animates the entire performance. Improvisation always contains the possibility of failure. Here that risk becomes the music’s secret fuel, as each phrase steps onto uncertain ground and finds footing just in time.

Part IIc arrives like a quiet epilogue whispered after the main story has ended. Its intimacy carries a gentle radiance. The closing gestures resemble a warm hand on the shoulder, a kiss on the cheek of a wanderer about to continue down the road. What remains is a small bundle of warmth carried forward into whatever lies ahead.

It’s easy to forget that Jarrett’s performance began just before midnight, after the opera audience had already departed and the city had slipped into a quieter rhythm. Jarrett stepped onto the stage at precisely that hour when the imagination becomes receptive to rarer signals. Perhaps this is why the music radiates with such unusual clarity. Under those conditions, suspended between today and tomorrow, even the smallest musical gesture appeared luminous.

All of which leads back to the peculiar solitude at the center of the recording. A lone pianist sits before a flawed instrument and invents an entire landscape from nothing. No bandmates share the burden. No written score provides direction. The artist listens to the room, to the objects at his disposal, to the faint murmurs of possibility that hover just beyond hearing. Music emerges like mist from a valley floor.

As is evident from my first attempt to describe this music in mere human language, the recording eludes definitive characterization. Words are the cloudy sky into which it has soared over the years. However, what language fails to capture finds perfect expression in sound. The piano speaks with a fluency that criticism can only admire from a distance.