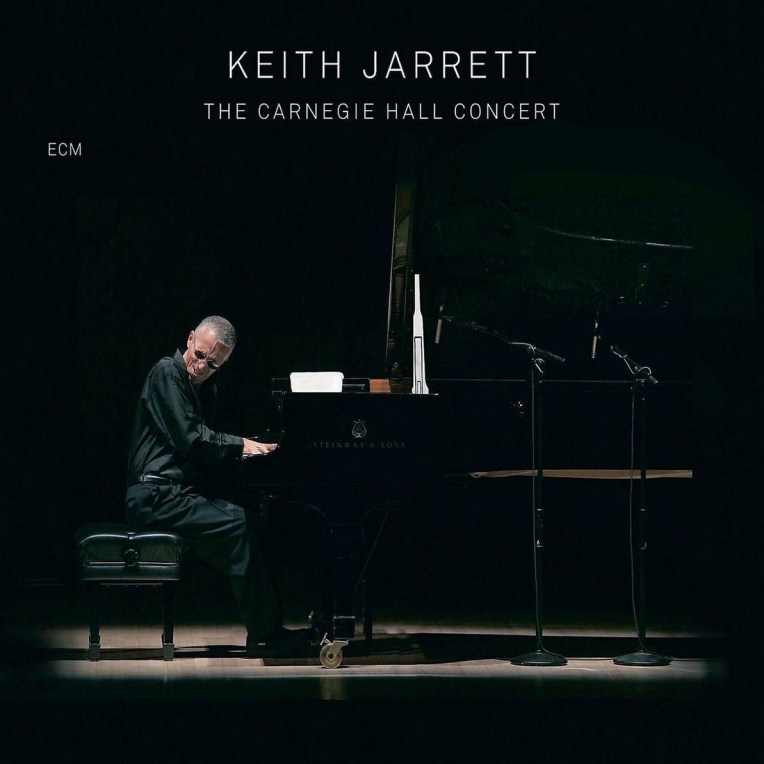

Keith Jarrett Trio

Standards I/II – Tokyo

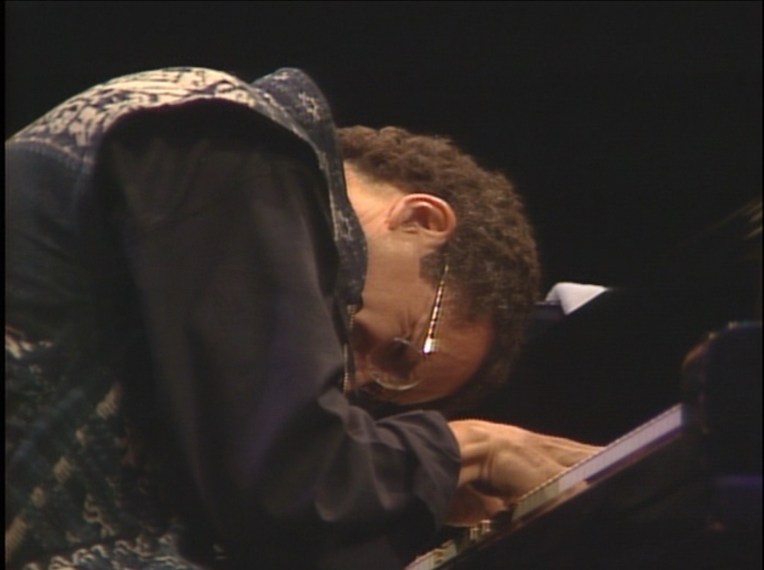

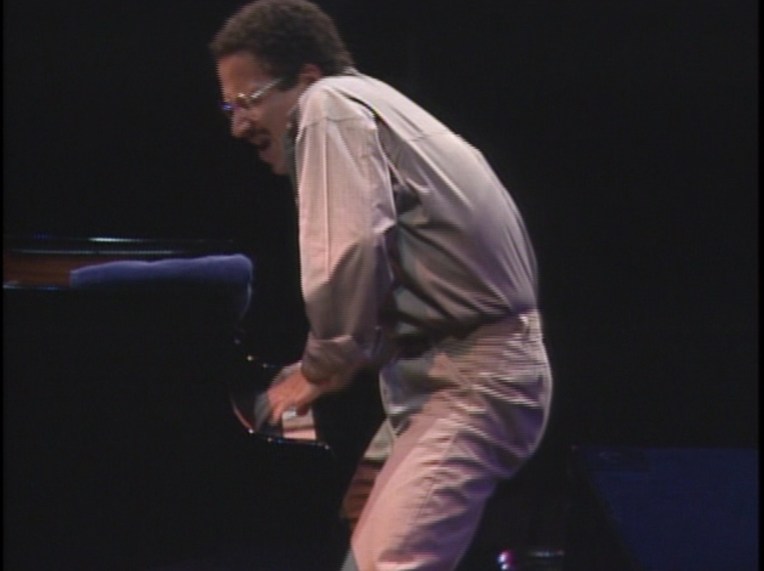

Keith Jarrett piano

Gary Peacock bass

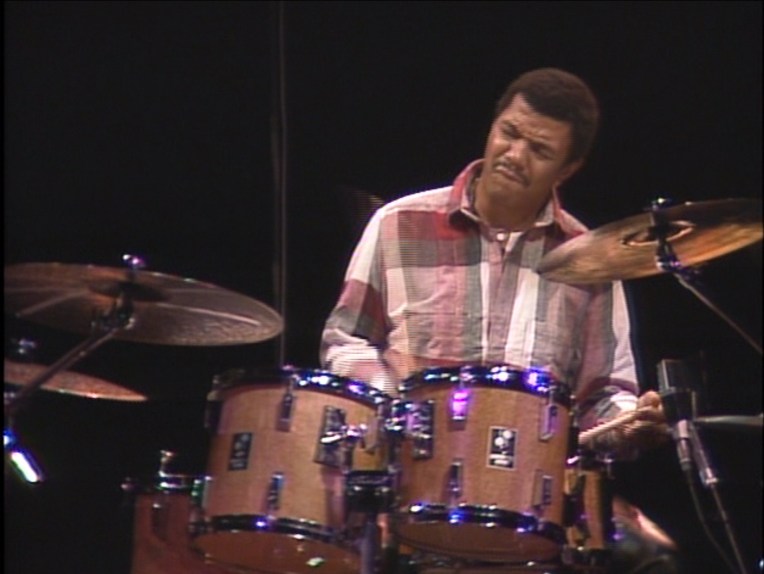

Jack DeJohnette drums

DVD 1

Recorded live in Tokyo, February 15, 1985 at Koseinenkin Hall

Director: Kaname Kawachi

Recorded and mixed by Toshio Yamanaka

Production coordinator: Toshinari Koinuma

Produced by Masafumi Yamamoto

Executive producer: Hisao Ebine

DVD 2

Recorded live in Tokyo, October 26, 1986 at Hitomi Memorial Hall

Director: Kaname Kawachi

Recorded and mixed by Seigen Ono

Production coordinator: Toshinari Koinuma

Produced by Masafumi Yamamoto

Executive producer: Hisao Ebine

Concerts produced by Koinuma Music

Standards I/II is an invaluable two-DVD archive of the Keith Jarrett Trio’s inaugural tours of Japan. The first, recorded at Tokyo’s Koseinenkin Hall on 15 February 1985, offers the pianist at his heartfelt best in an intro as tender as a drizzling rain. So begins a smooth version of “I Wish I Knew,” through the lens of which bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Jack DeJohnette illuminate the spectrum of this format like few others can. What distinguishes them, as made clear in this concert opener, is their consistent ability to surprise. Sure, the technical prowess required to carry off such florid versions of “If I Should Lose You” and “It’s Easy To Remember” is formidable to say the least, but how much more virtuosity there is to be savored in the ballads. The night-laden memories of “Late Lament” add softness to the set list’s emerging palette, even as they whisper in a language as crystalline as all the rest. This is a diamond in which every occlusion represents an opportunity for clarity. “Stella By Starlight” starts with Peacock and Jarrett emoting in space and time without allegiance to either, working into a 14-minute groove so sublime that it melts.

To be sure, the more upbeat tunes have a crispness all their own. “If I Should Lose You” finds Jarrett listening intently to his bandmates, who exchange tactile glances in anticipation of DeJohnette’s rolling play. But whether the drummer is riding the rails in “It’s Easy To Remember” or adding choice accents to a diagonal “God Bless The Child,” he leaves plenty of room for his audience to grow in kind.

Jarrett originals such as “Rider” and “Prism” showcase his penchant for gospel and Byzantine grooves. In these tunes the band reaches a high point of synchronicity, working a detail-oriented art into a genre all its own. Even the lighter “So Tender” retains full emotional accuracy, going all in via Peacock’s supernal melodizing. All of which leads to sixteen and a half minutes of soulful unpacking in “Delaunay’s Dilemma.” Peacock fascinates again in his soloing toward the finish line, while DeJohnette sings even as he punches his way toward bluesy victory.

The second Japan concert was recorded at Hitomi Memorial Hall, also in Tokyo, on 26 October 1986. This standards extravaganza is the regression to the previous concert’s progression, but loses no sense of integrity for its introversion. “You Don’t Know What Love Is” eases into things with sweeping finesse such as only Jarrett can pull off. It is followed by “With A Song In My Heart,” the meditation of which morphs into some solid invigorations. Peacock and DeJohnette share a flawless rapport, the drummer popping off that snare like a machine gun.

So begins an alternating pattern of valleys and peaks, which by the end leave behind an even more cohesive program than the first. We next dip down into a tune the trio plays like no one else: “When You Wish Upon A Star.” Jarrett’s rendering makes even the most familiar blossom anew with emotional honesty. The mastery on display in this quintessential example is as pliant as Peacock’s strings, and carries over into the interlocking tempi of “All Of You.” For this, the bassist leaps forward with the first of two solos, moving from robust to filigreed without loss of syncopation.

The bassist turns out to be the sun of this solar system, lathering a mysterious yet lucid “Georgia On My Mind” and a duly nostalgic “When I Fall In Love” with enough light to spare in conversation with his bandmates. DeJohnette, for his part, airbrushes the night sky in “Blame It On My Youth” and lets the groove be known behind “Love Letters.” And in tandem with Jarrett, he feeds magic into the masterstroke of “You And The Night And The Music.” Unforgettable.

Each of the three encores—“On Green Dolphin Street,” “Woody ’n You,” and “Young And Foolish”—is a virtuosic gem set to twinkling and reminds us that Jarrett and his associates came this far only by selecting their divergences lovingly.