“Open always, always watching, the eyes of my soul.”

–Dyonisios Solomos

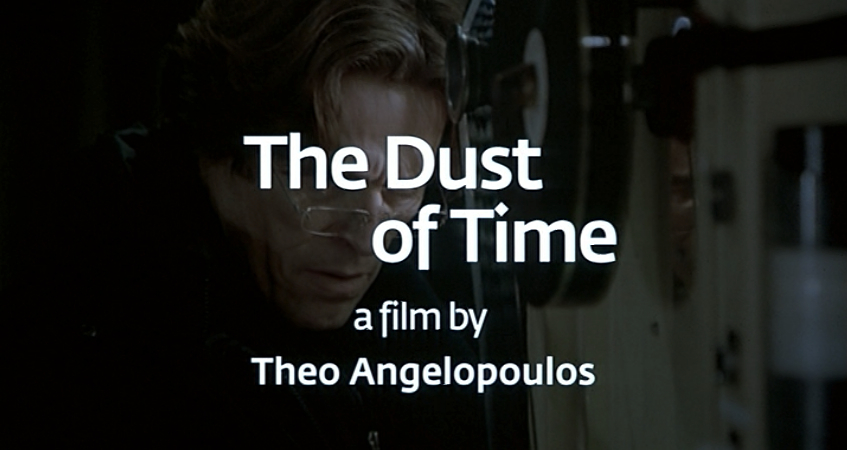

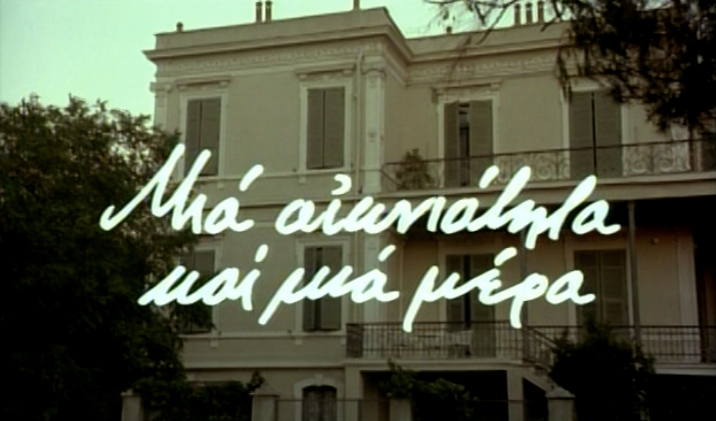

The Film

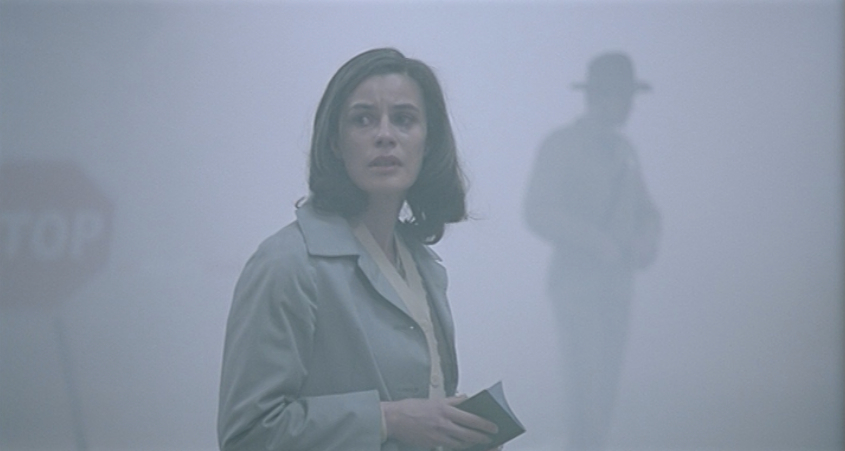

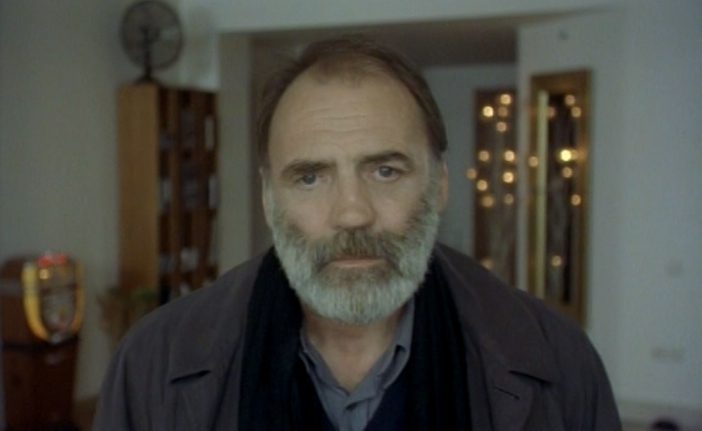

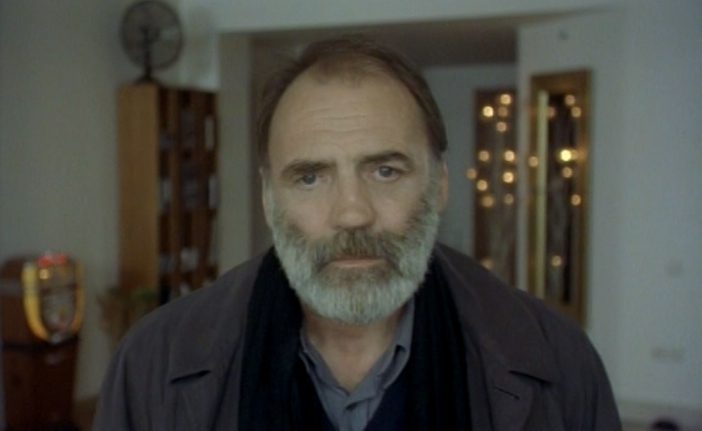

An ancient city, lost beneath the ocean. The stuff of history. Time, a young voice tells us, is “a child playing jacks on the beach.” A piano wafts through the image like a breeze carrying scents and sounds of retrospection—the film’s leitmotif. Here the past functions not as a repository for memory but as a palimpsest for a mind still practicing. It is the mind of Alexander (Bruno Ganz), an aging poet whose dark trench coat cuts a crow’s wing against director Theo Angelopoulos’s wintry palette. A slow approach to a window guides us to the film’s title by way of Alexander’s boyhood. The camera follows him as if through a ghost’s eyes.

When we first encounter Alexander as he is now, he holds a taste of the sea in his mouth…

…and clutches his throat as if breathing were a labor. This momentary inability to get words out is both curse and blessing: an obvious malady for a man of letters, but also a release from the world’s imploration to dress its dreariness in pretty semantics.

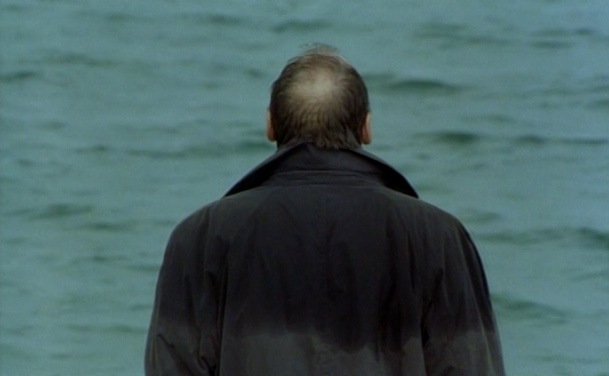

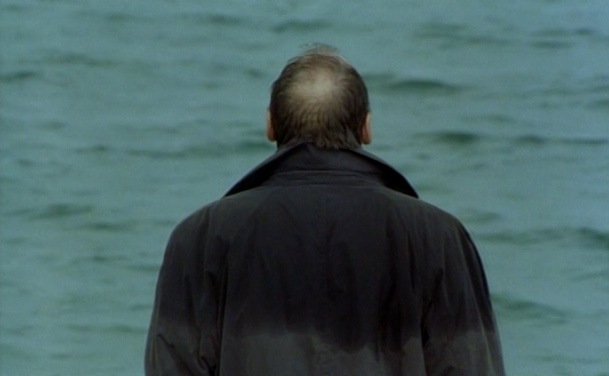

The sea follows Alexander. It is the tail of the dying comet that is his life. His dog looks toward that same sea, a place where music and memory are engaged in dance. A terminal diagnosis looms over him (his constant pill-popping brings rhythm to the narrative), mist over a landscape of uneven hills. He feels silence encroaching and fills it with regrets of unfinished work, of “words scattered here and there.”

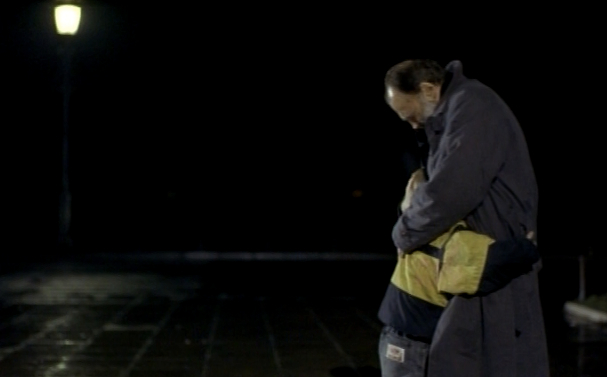

Alexander welcomes a boy (Achileas Skevis)—an Albanian vagrant washing windows at stoplights for petty cash—into his car. His whim begins a final poem, a magnum opus borne of action and sacrifice that can never manifest as ink and paper but rather unspools across light and film. Yet while this charity saves the boy from capture by police and gives us the film’s first smile, it comes at the cost of ignoring the other boys into whose meager routine of survival he had fallen.

Alexander knows the ripple effect of his actions. He feels the churning waters of time as a swallowing force. Its life-giving properties are so far removed from the here and now that it is all he can do to plunge his feet into the mud of recollection. After spending a lifetime waiting for progress, he will spend another waiting for regress. Angelopoulos’s title does not compare eternity and a day, but equates them.

As Alexander prepares to leave his everyday existence and spend his remaining days in convalescence, he brings the dog to his daughter, Katerina (Iris Chatziantoniou). The contrast between her upscale apartment and her utter yearning for a transparent ancestry are but surface to the inner sanctum of her father’s raw linguistic materials. She displays her anxieties among the art objects of her living room, where a wall catches the circumference of a projected clock. As the film’s symbol par excellence, it hovers like a dedication page torn from its binding and pasted where a window might be. In this manner Katerina turns her glitches into quantifiable space.

During this visit we learn that Alexander is completing an unfinished 19th-century epic by Dyonisios Solomos. “The Free Beseiged,” as it is known, is mired in the Greek War of Independence, from which it draws blood to fill its pen. Alexander has been working on the project since the death of his wife, Anna (Isabelle Renauld), who comes to us in flashbacks. And while Katerina may not understand why her father would ever wish to graft his words onto another’s, she flows through him like the returning sea when he gives her letters written in her mother’s hand. Through her reading, Alexander is read anew, revitalized as if by the boy whose fate he has influenced.

The sea is a trance, pillow of scent-filled houses. Sleep and silence cohabit its ever-changing shoreline. Through her daughter’s voice, a resurrected Anna links newfound maternity with love, safety, and breath. The vulnerability of her body engenders absolute trust in, and safety for, her blossoming child. For Katerina is indeed a flower, the center of a family gathering in the sunlit prime of a warmer era. Even in life, Anna was constantly on the verge of dissolving, a wanderer in love. Alexander is moved beyond comfort, for he knows that his dissolution will bring him closer.

Like all reveries, this one is all the more poignant for its brevity and it is Katerina’s husband who breaks its spell. Put off by the presence of what in his eyes can be nothing more than a haggard vagabond, he tells Alexander he has sold the old house by the sea—the very house where Katerina tumbled into maturity—and that it will be demolished. He also takes unkindly to animals and questions any obligation to welcome the dog into his home.

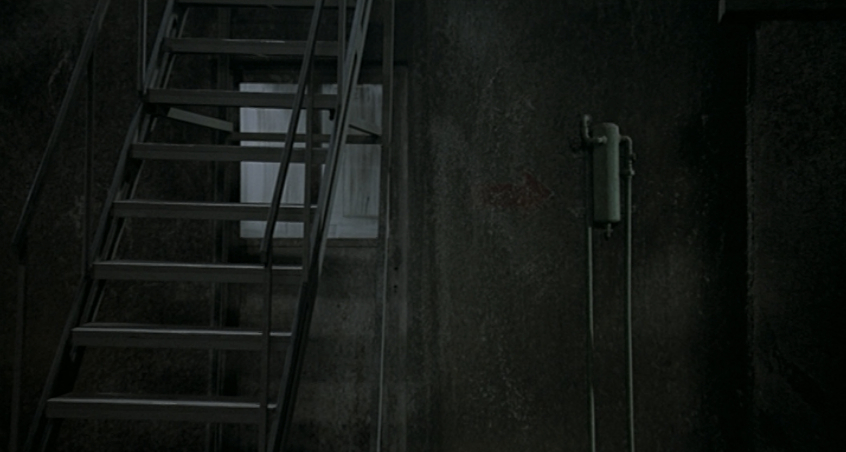

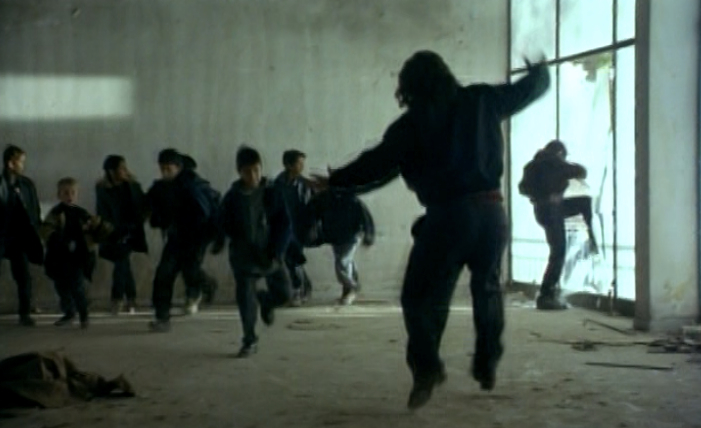

The streets, paved in articulate indifference, keep Alexander in check. They are the insignia of a publisher far grander than anything he can contemplate with his ties to speech. In opening himself to a stranger, Alexander realizes he has found in the boy a beacon—not of hope, but of evenness. This balance is upset when he witnesses the boy being thrown into the back of a cargo truck.

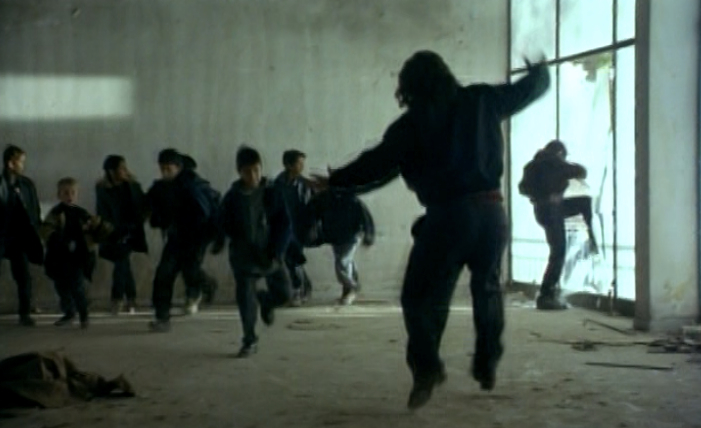

He follows the vehicle to a shady warehouse where other urchins have been plucked from their rocks and are being sold into an invisible market. The boys, however, are wise to this and make a run for it in a ballet of quick thinking and broken glass.

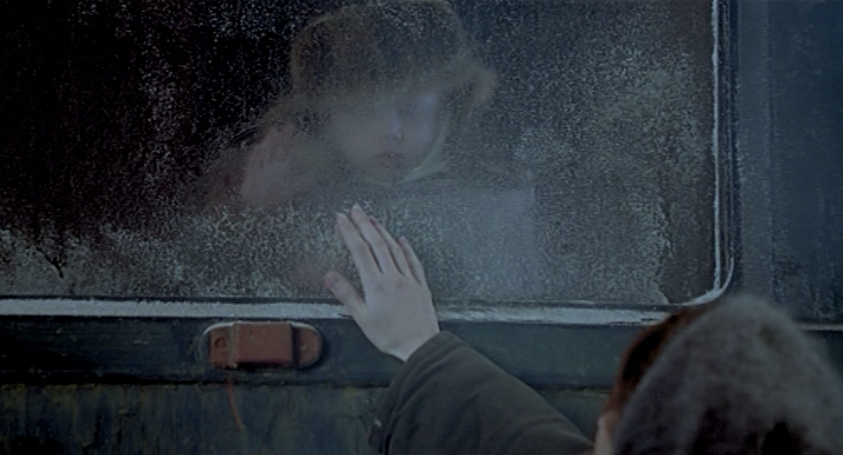

In the ensuing chaos, Alexander saves the boy of his interest, giving all the money on his person in exchange. He puts the boy on a bus going toward the Albanian border, both in the hopes of losing him before he loses himself and in the hopes that there might be a home to return to.

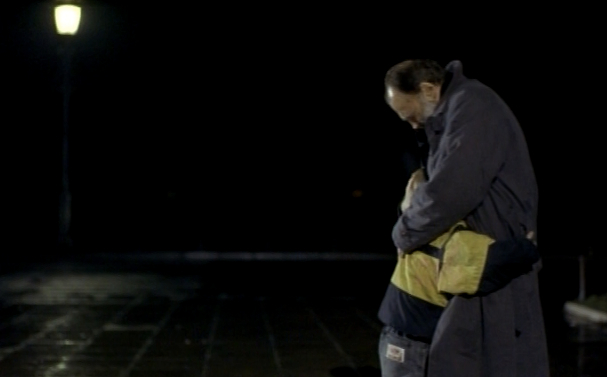

The boy comes back to Alexander, having found a home in presence of the bearded stranger. He sings a children’s song from his homeland, tells Alexander of crossing the border, thereby revealing a likeminded fixation on language. Alexander takes him to the border, but they run when the boy tells him he has no one.

Alexander tells him the story of the poet Solomos (Fabrizio Bentivoglio), Greek but raised in Italy, who returned to his homeland when he heard the Greeks were rising against the Ottomans. He does not speak the language, and so he buys words from the locals. Across a night “sown with magic” he travels, reaching deep into his reservoir of sentiments to produce the “Hymn to Liberty.” It remains a significant verse for Alexander, a bid for freedom from language, through language.

In the end, he entrusts the dog to his housekeeper, Urania (Helene Gerasimidou), interrupting her son’s wedding to do so. Spectators hanging from the gates mirror those at the border, each a living puppet frozen in the wake of a changing tide.

This leaves the boy, Alexander’s only link, his only mirror. “You’re smiling, but I know you’re sad,” the boy tells him. Such contradictions—in the end, not really contradictions at all—are essential to Angelopoulos’s cinematic world, a world where light and dark are so permeable as to be unquestionable. For while Alexander’s cape is the shadow of his deteriorating self, of a body blurring into lifelessness, it is also a flag whose communication harnesses wind like a sail.

He is a man devoid of contact, yet who is touched by humanity; a man in self-imposed exile, yet who knows the landscape as if it were his own; a man known for words, yet who pays for them with emotional currency. The boy wants to say goodbye, but Alexander convinces him to stay, will not accept that his hand may bring about another end.

Thus the camera looks beyond the curtain into the reflecting pool of the human condition.

His films are unfinished, stitched yet tattered. In allowing their seams the privilege of coming undone, he delivers messages devoid of hyperbole. The zoom, for example, sheds its derivative qualities in such a context, seeking not to focus our attention so much as to remind us of limitations. As in the films of Andrei Tarkovsky, the occasional close-up shocks with its candor, reaches into the pit of our complacency and stirs up the love we have forgotten. When Alexander turns his back on us, he turns his back on the world.

The Soundtrack

Composer Eleni Karaindrou has her finger so firmly on the pulse of Angelopoulos’s ethos that her flesh has melded with his images. Yet there is something more than the combination of sight and sound going on in Eternity and a Day, for this more than any other film she has soundtracked is an ode also to time.

Eleni Karaindrou

Eternity and a Day

Vangelis Christopoulos oboe

Nikos Guinos clarinet

Manthos Halkias clarinet

Spyros Kazianis bassoon

Vangelis Skouras french horn

Aris Dimitriadis mandolin

Iraklis Vavatsikas accordion

Eleni Karaindrou piano

String Orchestra La Camerata Athens

Loukas Krytinos director

Recorded March and April 1998, Athens Concert Hall

Engineer: Andreas Mantopoulos and Christos Hadjistamou

Produced by Manfred Eicher

The title of the first piece, “Hearing the Time,” would seem to say as much: just as Angelopoulos puts an eye to lens, so too Karaindrou puts an ear to history. She draws thick yet airy wool over our eyes, that we might view the world through the blur of fibrous experience. Over an expanse of archival strings we hear a distant relay between violin and accordion. These punctuations are not ruptures but voices from below. The composer at the keyboard elicits “By the Sea,” a humid snapshot that segues us into the mandolin accents and silken oboe line of the “Eternity Theme.” As Beethovenian cellos churn, we think back to its corresponding scene in the film, in which we find Alexander listening to this very music on the radio. He shuts off his mechanical translator and looks out across to the other apartment complex, where the same music flows from another window. “Lately” he muses, “my only contact with the world is this stranger opposite who answers me with the same music.” Perhaps true to character, he decides against pursuing this fascination: “It’s better not to know…and imagine.”

And imagine is all we can do when taking this soundtrack on its own terms. The theme echoes throughout its architecture, inflected differently by each soloist. A bassoon evokes tears colored by fate, while clarinets drip from the great beyond with tastes of once-forgotten joy. A traditional wedding dance fills the air with bright steps, contrasting almost painfully with the solitude of “Bus,” and lends relative sanctity to Ganz’s recitation in “The Poet.” Yet it is in a little piece called “Borders” that the fluidity of his embodiment is clearest. Through it we realize that harmony needs change.

Like the film itself, the score of Eternity and a Day creates a somewhere far removed from its content yet which is equally cinematic. It is a looking glass unto itself, a kaleidoscope named “then.”

<< Kenny Wheeler: A Long Time Ago (ECM 1691)

>> Evan Parker Electro-Acoustic Ensemble: Drawn Inward (ECM 1693)