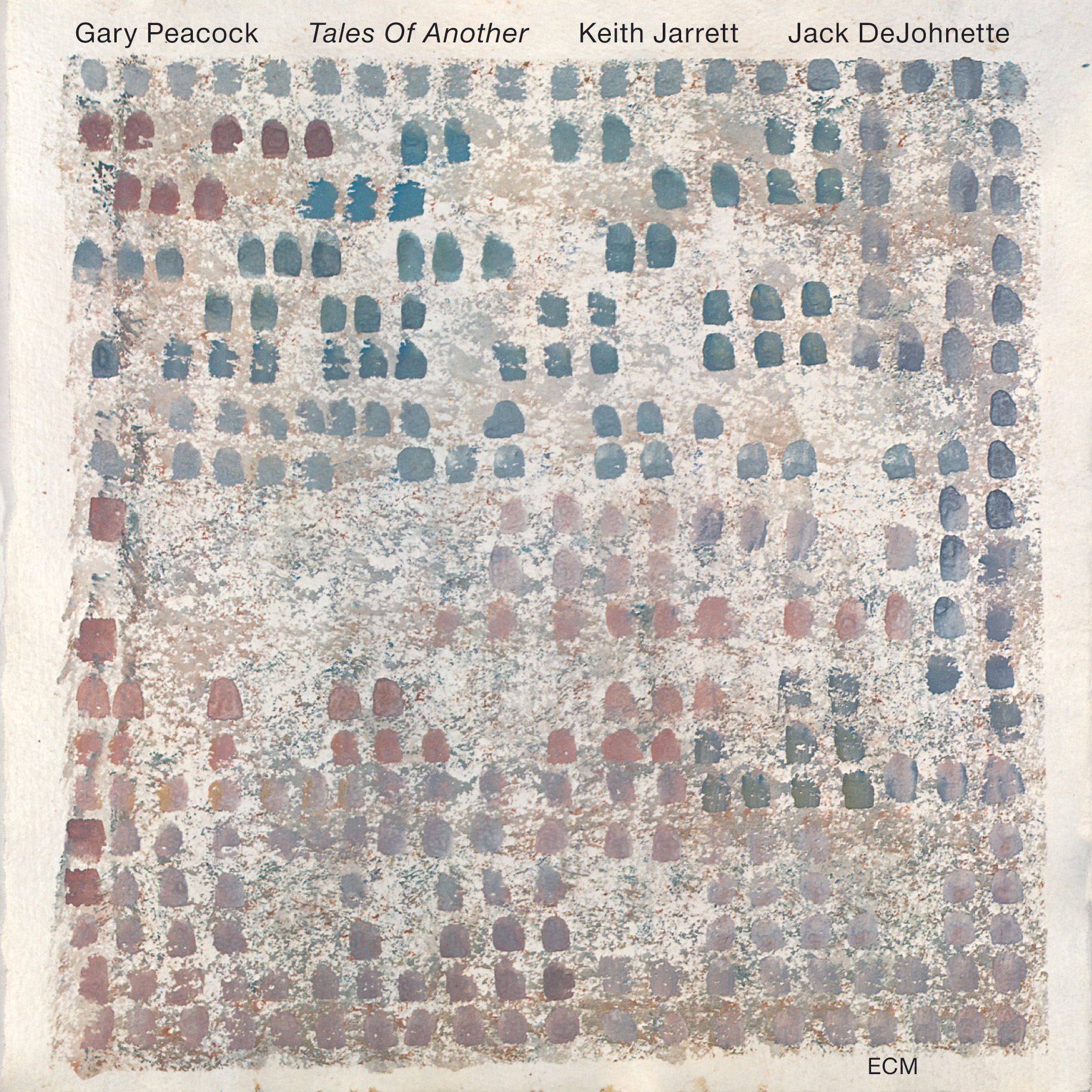

Keith Jarrett Trio

Setting Standards – New York Sessions

Keith Jarrett piano

Gary Peacock double-bass

Jack DeJohnette drums

Recorded January 1983 at Power Station, New York City

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

“I feel we are an underground band that has, just by accident, a large public.”

–Keith Jarrett, on his trio with Gary Peacock and Jack DeJohnette

The piano is considered by some to be a “complete” instrument. On it, one can compose anything from a simple etude to the grandest of symphonies, and its most adored practitioners may be said to be whole at the keyboard. The beauty of a player like Keith Jarrett is that he makes the piano sound so gorgeously incomplete, emphasizing as he does the unfathomable volume of sentiments he would convey through it if given the time. As it is, we get the barest taste of immortality. Jarrett carries the entire weight of any composition in even the most linear of melodic lines. In doing so, he opens doors that few could step through unharmed.

And yet, step through them the rare soul has, and perhaps none so ingenious as bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Jack DeJohnette. When listening to the bliss that rolls off Jazz’s proverbial tongue throughout Setting Standards, however, we must constantly remind ourselves that the three albums collected therein represent the first time Jarrett, Peacock, and DeJohnette had ever stepped into the studio as a bona fide trio. The three men were, of course, far from strangers, but produced such unreal synergy in these unrehearsed sessions that they might as well have been cut from the same cloth. The trio would also prove in a way cathartic for Jarrett, who was already beginning to buckle under the pressures of an increasingly demanding listenership. For this, he turned to the tried and true, if not to the plied and blue, for solace.

With Standards, Vol. 1 (ECM 1255) Jarrett and company set things straight from the get-go by showing us the “Meaning Of The Blues.” This swath of melodious rain is the trio form at its best and never lets up until the very end. DeJohnette’s charcoal sketches in background add a quiet boldness. “All The Things You Are” is a more lighthearted, though no less intense, construction, and haunts Peacock’s nimble fingerwork with a visceral chord progression. Smoothness abounds in “It Never Entered My Mind,” a gentle tune that puts a new twist on the pessimism of balladry by resolving itself at moments into a hopeful groove. A hefty splash of freedom awaits us in “The Masquerade Is Over.” Peacock is on fire here, giving just the sort of fuel that Jarrett sets to such glorious conflagration. The latter’s soloing proves that not only is the masquerade over, but also that these musicians never hid behind masks in the first place. If any single facet of this jewel can be singled out, it is the stunning fifteen-and-a-half-minute rendition of “God Bless The Child” that concludes it. Peacock excels, taking the swing around the bar and back again.

<< John Surman: Such Winters of Memory (ECM 1254)

>> Charlie Mariano: Jyothi (ECM 1256)

… . …

Standards, Vol. 2 (ECM 1289) is a shaded glen in Volume One’s verdant forest. Its mood is summed up perfectly in the title of the opening “So Tender,” which after a slow intro falls into the unity that so distinguishes this trio. Jarrett dances not on air but on fire in his pointillist lines, while Peacock and DeJohnette both captivate with their subtle, popping sound. “Moon And Sand” is an equally smooth ride through less traveled territories and finds Jarrett in a gentler mood. DeJohnette is also at his most delicate here, drawing circles in the sand with his brush. For “In Love In Vain” Jarrett spins from thematic threads a twin self, who for all his similarities breathes a different sort of politics in one of the set’s finest tunes. With every grunt, Jarrett voices only the tip of his creative iceberg. Peacock delights with a very elastic solo, which no matter how far it stretches stays locked to its theme as if by finger trap. Jarrett is at his lyrical best in “Never Let Me Go,” and skips to his Lou in “If I Should Lose You” before laying down the poetry of “I Fall In Love Too Easily” with a thick, tangible power.

<< Eberhard Weber: Chorus (ECM 1288)

>> Everyman Band: Without Warning (ECM 1290)

… . …

Prior to the release of Setting Standards, I hadn’t yet encountered the free play session that is Changes (ECM 1276) and what a joyful surprise it turned out to be, for never has the trio emoted in such a blissful mode. “Flying” is a heavenly diptych honed in delicacy and abandon. Here the band describes a decidedly aquatic territory, each tattered thread of melody flowing like the tendrils of a throbbing deep-sea creature whose eyes are its hearts. Jarrett spreads and shoots straight like an octopus, every pad suctioning to a new and exciting motif. Peacock, meanwhile, threads his fingers through a vast oceanic harp, stretching his emotive capacity to its limits. DeJohnette surfaces with a deeply digging solo before we end with Jarrett alone in a quiet, dissipating reflection. Peacock trails his starfish of a bass line through the pianistic coral reef of Part 2, he and DeJohnette inking their solos before hollering their way into an inescapable passion. The set ends in the refractions of “Prism.” And indeed the trio as a unit is not unlike a prism, separating every ray of light into its composite colors, likewise every ray of darkness into its whispered secrets. Jarrett’s expulsions heighten every inarticulable word that he writes, the breath of an energy that cannot be contained. The farther these reveries drift, the more life experience they carry back into the fold when they return.

<< Arvo Pärt: Tabula rasa (ECM 1275 NS)

>> John Adams: Harmonium (ECM 1277 NS)

… . …

In a society gone astray from musical immediacy, it’s safe to point out Jarrett’s nexus as one of the more reliable vestiges where melody still blooms. With an average track length of nine minutes, these are quiet and endlessly interesting epics. Say what you will about Jarrett’s singing, which has sadly turned not a few off from these recordings, but I believe Peter Rüedi puts it best in his insightful liner notes when he says, “His groans and vocal outbursts, considered by many to be a quirk, are in fact nothing but a form of suffering at the thought that the abyss between the piano and sung melody can ultimately never be bridged, not even by Jarrett himself.” To these ears, Jarrett’s voice welcomes us into the intimacy of his creative spirit, so unfathomably expanded in the company of two fine musicians (and even finer spirits) whose talents can’t help but sing in their own complementary registers. And on that note, we mustn’t forget the contributions of Jarrett’s band mates, who constitute far more than anything the mere rubric of “rhythm section” might ever imply. How can we, for example, not shake our heads in wonder at DeJohnette’s consistent inventiveness, which singlehandedly reshaped the idioms at hand. And then there is Peacock, who for me is the bread and butter of the first two sessions. So carefully negotiating his path through various leaps and bounds, he seems to anticipate everything Jarrett throws his way. Just listen to his soloing on “It Never Entered My Mind” and “God Bless The Child,” and these words will mean nothing.

Through the two standards albums, Jarrett put the “Song” back into the Great American Songbook, and in Changes enlarged it with “Prism.” Now given the proper archival treatment in this 3-disc Old & New Masters edition commemorating 25 years of music-making, this unassuming surge of sonic bliss is now ours to cherish at will.

The camaraderie expressed in the booklet’s final session photo speaks for itself: