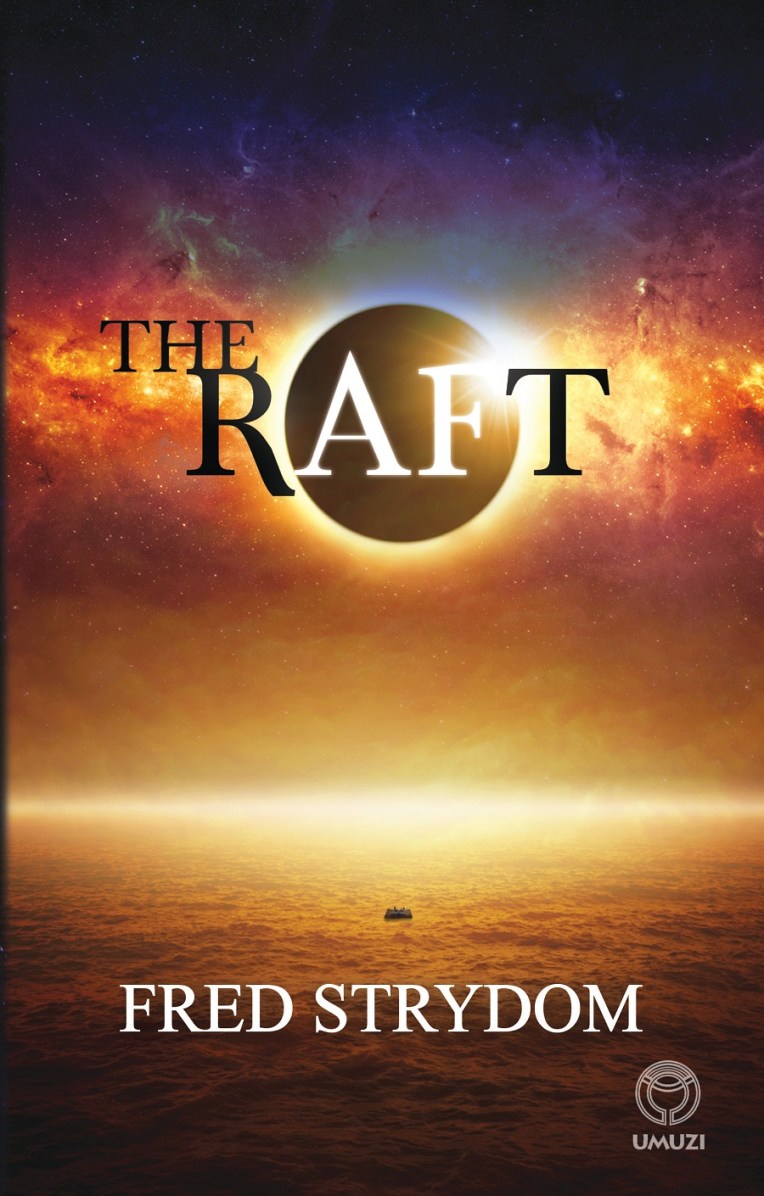

To a growing list of South African science/speculative fictionists (think Lauren Beukes and Sarah Lotz), one must add Fred Strydom, his novel The Raft being one of the most unnerving dystopian tales to emerge in recent memory. Memory is indeed paramount in Strydom’s feature debut, most of which takes place after Day Zero, when a mysterious, piercing whine reset the entire Earth to mental zero in what one character calls “baptism by amnesia.” Since then, humankind has had to rebuild itself amid waves of intermittent recall and cerebral puzzle-piecing.

The novel awakens on a beach through the eyes of its narrator, Kayle Jenner, who has managed to regain enough semblance of self to know his son Andy has gone missing and that he must find the boy at all costs if he is ever to feel whole again. The island he calls home — or which is, more accurately, dubbed home for his sake — confirms an unusual brand of apocalypse, one not of environmental but mental obliteration. Survivors have broken off into communes ruled by a dictatorial regime that calls itself The Body, whose role is to ensure that no one remembers too much of former days. Armed with quasi-communist ideals, the island’s overseers go to questionable lengths to ensure that none of its inhabitants is sullied by the taint of possession.

Kayle’s emotional palette is a spectrum of doubt, hope, and possibility. He holds on to dreams and nightmares alike as the only bastions of true selfhood. Assaulted by names and faces which should mean something to him but only seem to mock him behind closed eyes, he fears even these will be taken away while undergoing compulsory interrogations, during which members of The Body grill him on notions of God, power, and the nature of reality. The nominal goal of these “interviews” is to disconnect him from the hierarchical and materialistic tendencies that once pulled the globe into a spiral of moral depravity. As outlined in their ideological handbook, The Age of Self Primary, of which expository pericopes dot the novel, it was an immoral age done great service by Day Zero, a wrinkle in time rightly ironed out by catastrophe and firmed by the starch of psychological reinforcement. Kayle fails to see it this way, but with no foreseeable exit it’s all he can do to avoid projecting his fear on to a cosmos where every star becomes the wink of a derisive eye.

Details of pre-dystopian life are scarce but adequate enough to imagine one possible future for ourselves. Compulsory advertisements burned into bread by smart toasters, palm-reading screens that open and start cars, and whisper-quiet transports give glimpses of the conveniences left behind for the new primitivism. Much of the novel’s drama, however, turns the gestures of relatively organic technologies into life-altering changes, and by these Kayle will stumble across the truth of what his world has become. But it is the commune, for him “a place of bareness,” where personal demons are given room to roam. The description could hardly be more accurate. On the commune, free will is as intangible as the lives the island’s inhabitants struggle to remember, and salvation withered beyond ornament.

The novel’s titular raft is one of three reserved for the island’s wrongdoers, who are drugged, strapped to its floating planks, and forced to endure the mood swings of an unforgiving sea for days on end. When Kayle finds himself so punished for an “indiscretion” better withheld for the reader’s discovery, his journey toward finding the cause behind Day Zero and the whereabouts of his son carries him to landscapes at once forgiving and hostile.

By writing almost entirely in the first person, Strydom has dared break a strident rule of the debut novelist. To be sure, nearly all of his characters, regardless of age or background, speak with a likeminded vocabulary and cadence, while the few who don’t must rely on blatant verbal ticks — witness the inexplicable stutter of Kayle’s later accomplice — to differentiate themselves. Then again, this has the added effect of emphasizing the fact that everyone has been degaussed to some base mode of communication, and that The Body’s brainwashing has been effective.

There is, furthermore, a slew of flavor text to wade through, and similes are as frequent as the crack of a bat at a baseball game. Thankfully, Strydom’s are so lovely that one can enjoy the creativity of his writing without getting too bogged down in indulgent wordplay. One might further interpret his metaphorical twists as attempts on Kayle’s part to assert connections in a broken world (here is an author who values the scope of possibility as much as the possibility of scope). That Strydom’s educational background is in visual media will therefore come as no surprise. He writes like a filmmaker. His gifts for atmosphere are downright videographic, and at times his descriptions of places, in especial light of the island theme, feel like something out of Robyn and Rand Miller’s Myst series. He employs another cinematic and, given the novel’s conceit, rather ironic device: that of perfect recollection, as characters share conversations and letters verbatim when recounting personal stories. But Strydom’s love for those stories, and for the characters telling them, trumps any minor quibbles, leaving us with a destination more than worth the travel required to get there.

(This review originally appeared on the now-defunct SF Signal, and is archived here.)