John Abercrombie

The First Quartet

Release date: November 6, 2015

The three albums reissued for this Old & New Masters set were the missing pieces in John Abercrombie’s discographic puzzle for ECM. Released less than two years before his death in 2017, the present collection comprises a vital document not with regard to its bandleader but also the label he would call his primary home after the release of Timeless in 1975. As Abercrombie recalls in John Kelman’s superb liner notes, “[T]hat was my first real break; it helped me find my own way, because I was basically a John McLaughlin rip-off at the time.” Whether we agree with the latter self-assessment, the album was a watershed moment of jazz history in which Abercrombie and producer Manfred Eicher collaborated on a lasting statement.

Abercrombie, Kelman goes on, fell in with bassist George Mraz and drummer Peter Donald while studying at the Berklee College of Music in Boston (where he was roommates with Mraz and keyboardist Jan Hammer). After moving to New York, he squared the circle upon meeting pianist Richie Beirach. While building his profile as both musician and composer, Eicher gifted him with a Revox reel-to-reel tape recorder, which along with the piano would become his primary compositional tool for years to come. It was around that time that the quartet featured here came together in the studio under Eicher’s watch. As Kelman notes of their first session, “Arcade doesn’t sound like a nascent group still finding its way.” Indeed, what we have here is music that comes to us as if midstream, matured and ready to be experienced without any other filter than the decades it took to reach us in digital form.

Arcade (ECM 1133)

John Abercrombie guitar, electric mandolin

Richard Beirach piano

George Mraz bass

Peter Donald drums

Recorded December 1978 at Talent Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Original release date: March 1, 1979

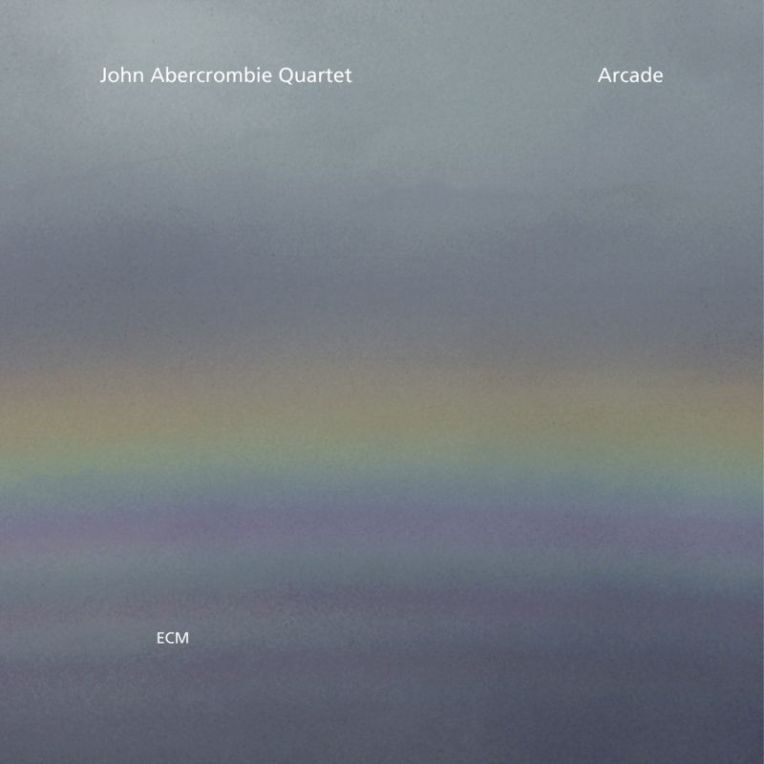

Toward the end of Akira Kurosawa’s Kagemusha, a rainbow spreads its band across the ocean to warn General Katsuyori not to proceed into the Battle of Nagashino that lies ahead, lest he meet with certain doom. Tragically, he ignores it and rushes himself and his men into an all-out massacre. Such omens are rare outside of the cinematic imagination. And yet, here we find a similar image gracing the cover of Arcade, signaling to us a music that doesheed that omen and luxuriates in the sonic benefits of its deference to a higher power.

Film still from Kagemusha (1980)

The title track, with its buoyant bass line courtesy of George Mraz (onetime member of the Oscar Peterson Quartet) and an effervescent Richard Beirach (rightful heir to the Tatum/Evans legacy) on piano, frames John Abercrombie’s adventurous fingers like gloves, making shadow puppets against the taut screen of Peter Donald’s drumming. This formula works from the get-go and provides plenty of magic from which the quartet spins one glorious melody after another. A splash of rain brings us to the “Nightlake” with downcast eyes as Abercrombie lays his rubato soloing over a liquid rhythm section. The results showcase the quartet at its best. “Paramour” is another stunner, working over the listener in waves. Mraz digs deep into his emotional reserves for this one. Meanwhile, things are a bit more cosmic on “Neptune,” where arco bass cuts a swath of moonlight in nebular darkness. Abercrombie launches tiny rockets into the stars with his electric mandolin, tracing new constellations on the way to becoming one himself. In closing, the group shows us what “Alchemy” is all about. From its lead filings arises a golden phoenix. Every appendage is an instrument animating the harmonious whole, tickled by Beirach’s ivory and gilded in a layer of cymbals. As its heart contracts, the guitar lets out a plaintive cry, running ever so delicately into the shadows of resolution.

Abercrombie’s pinpoint precision abounds, his mid-heavy picking amplified to buttery sweetness, and shares notable interplay with Beirach. Over a yielding backing, these sustained reverberations occasionally coalesce in bright tutti passages. The resulting sound is enchantment.

<< Walcott/Cherry/Vasconcelos: CODONA (ECM 1132)

>> Tom van der Geld: Path (ECM 1134)

… . …

Abercrombie Quartet (ECM 1164)

John Abercrombie guitar, mandolin guitar

Richard Beirach piano

George Mraz bass

Peter Donald drums

Recorded November 1979 at Talent Studio

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Original release date: 1980

One year after debuting with Arcade, the John Abercrombie Quartet cut out the auditory paper doll that is this curiously overlooked successor. What set the quartet apart from its contemporaries was not only the fluid playing of its frontman and the ways in which it intertwines with that of musicians who are beyond intuitive, but also the sense of development in the structuring and ordering of tunes. Beginning with the pianistic groove of “Blue Wolf” and ending on the acoustically minded “Foolish Dog,” this self-titled peregrination winds itself into a tour de force of solemn virtuosity. From Beirach’s overwhelming cascades to Mraz’s contortions, we encounter a virtual entity of unity whose heartbeat counts off to Donald’s drumming and whose eyes glow with Abercrombie’s characteristic pale fire. This body unfolds into a misty landscape, where the gusts of “Dear Rain” spread melodies into harmonic pastures. Looser gestures like “Stray” (here, both verb and noun) share appendages with the resignation of “Madagascar,” which falls like a sheet from a clothesline in an oncoming storm. As the quartet grows in, Abercrombie’s gentle remonstrations graze the bellies of clouds with the barest touch of curled fingers, allowing “Riddles” to build their conversational nests in the branches of an undisclosed longing.

No matter how “into it” these musicians get, they always display an admirable sense of control, so committed are they to the thematic altar around which they cast their spells. There is a sound that lingers on the palate, one that finds in its cessation the birth of something new.

<< Azimuth: Départ (ECM 1163)

>> Gary Peacock: Shift In The Wind (ECM 1165)

… . …

M (ECM 1191)

John Abercrombie electric and acoustic guitars

Richard Beirach piano

George Mraz bass

Peter Donald drums

Recorded November 1980 at Tonstudio Bauer, Ludwigsburg

Engineer: Martin Wieland

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Original release date: 1981

For its third ECM outing, the John Abercrombie Quartet produced this viscous and mysterious entity known simply as M. This seven-part exercise in burnished reflection plows its foggiest waters in “Boat Song.” Abercrombie’s guitar weeps like bells over a harbor, skimmed for flotsam by Beirach’s somber piano. At nearly ten minutes, this is the longest track of the album, and its darkness haunts all that proceeds from it. We encounter this also in “To Be” (a rubato wave notable for Mraz’s effortless bassing), and the harmonic inversions of “Veils.” Here, Abercrombie’s sinewy melodic lines stretch farthest, slowly immersing hands into the “Pebbles” in which we find closure. Donald’s drumming is particularly fine here and shines like sunrays from cloud-break.

(Photo credit: Rick Laird)

Despite Abercrombie’s often-piercing swan dives and a pirouetting rhythm section, even the liveliest moments in “What Are The Rules” (a rhetorical move proving there need be none) or “Flashback” never lift their feet too high off the ground. The latter’s circular conversations draw around us a perimeter that we are free to overstep. Yet after being bathed in such sonic finery, we feel reluctant to do so. The result is one of Abercrombie’s lushest albums, with a somewhat obscure and tinny production style that writes a different story every time.

Taken as a trilogy, these albums are a time capsule of creative evolution into which the listener may step in, reading each tune like a cross-section of its own becoming in service of a whole that will only continue to grow as it ages now—remastered, revitalized, and released for all to share.

<< Pat Metheny & Lyle Mays: As Falls Wichita, So Falls Wichita Falls (ECM 1190)

>> Rypdal/Vitous/DeJohnette: To Be Continued (ECM 1192)