Charles Lloyd

Quartets

Not only is saxophonist Charles Lloyd a gentle warrior; he is a fierce dancer. By “fierce” I mean not in the manner of a predator but of sunlight: which is to say, all the more life-giving for his quiet grace. With Lloyd, at the time of this writing, in his 77th year, the critics will tell you he has never sounded better. But the simple fact is: he never sounded worse, either, as attested by the refined levels of meditation achieved on the five albums collected for this essential Old & New Masters boxed set from ECM. Indeed, meditation is an unavoidable flower in the field of his biography, as he famously walked away from the stage in the early 1970s, only to return to the horn a decade later with formidable selflessness. This period also saw his association with producer Manfred Eicher take first flight. Listening to these albums as a set, however, one realizes that his comeback was not the most important celebration. His truest essence as a musician remained cupped like a pocket of air in a lotus in which was contained a universe of song. And so, to assert that Lloyd was at last going forward is to do his spirit a disservice. If anything, he was going inward.

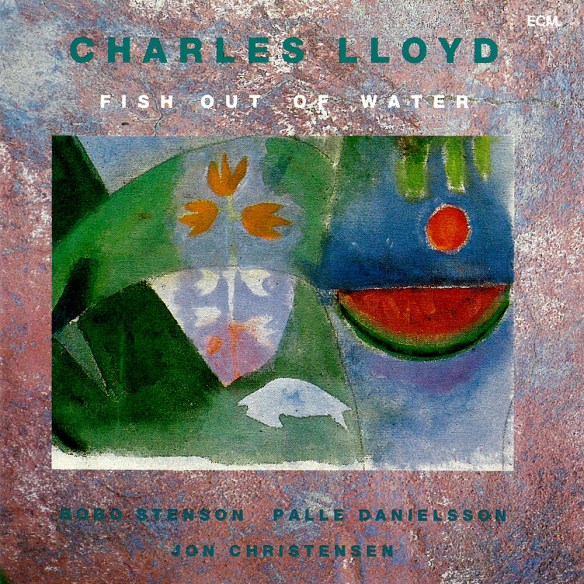

Fish Out Of Water (ECM 1398)

Charles Lloyd tenor saxophone, flute

Bobo Stenson piano

Palle Danielsson bass

Jon Christensen drums

Recorded July 1989 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

As Thomas Conrad notes of Lloyd in his accompanying reflections, “With eight notes, he can put you in the presence of his immortal soul.” And from the opening breaths of this ECM debut, the truth of Conrad’s statement becomes crystal. Here Lloyd is joined by pianist Bobo Stenson, with whom he would forge a significant working relationship, and Keith Jarrett’s European rhythm section: bassist Palle Danielsson and drummer Jon Christensen. Lloyd’s signature tenor, smoky of flavor and viscous of texture, floats through Stenson’s smooth action at the keys in the nine-minute title cut, which opens a program of seven originals. The delicacy of these two melody makers is the album’s bread and butter, as intensely apparent between notes as in them. Stenson draws freshly honed memories from Lloyd’s comforts, while the reedman takes pause and feeds back into the loop with darker nuances. The unwrapping of lyrical presents continues under the Christmas tree of “Mirror,” throughout which brushed drums and a resonant bass provide a landscape of fulcrums on which Lloyd balances smooth hits and fluttering asides alike, only to diversify the climate with flute in the contemplative “Haghia Sophia.” Again, from this Stenson manages to emote so complementarily that we almost get lost in the swirling oceanic foam from which arises a tenored Aphrodite. “The Dirge” is another drop into a limpid pool of soul that is reason enough to ingest this album’s nourishing vibes.

Two grooves await us in “Bharati” and “Eyes Of Love.” The former is seek, refined, and oh so moving. Lloyd speaks mostly in half-whispers, never louder than a private declaration, while the latter unfolds some of his softest playing on record. A buoyant yet introspective solo from Danielsson trips us into the rejoinder, which keeps the cool, blue fires stoked well into the flute-driven “Tellaro.” Lloyd releases Stenson adrift as if a flower upon a river, swimming as a fish beneath him into a forest where we cannot follow.

Mythology would like paint Lloyd’s hiatus prior to this album as a period of soul searching, during which he is said to have nearly abandoned music, only to return refreshed and pouring his all into the art form that so defines him (if not the other way around). And yet we clearly see that in the recordings since his soul searching has never stopped, for it continues to inhabit every breath that passes his reed. Even when Lloyd isn’t playing, there always seems to be a thin line connecting every stretch of silence. In this respect, we find here a spiritual level of jazz from artists all the more prodigious for their humility. In spite of their incendiary potential, they choose to cook rather than flare, each bringing his sensitivity to bear upon these insightful forays into melody and surrender. Tender to the utmost.

<< Shankar: nobody told me (ECM 1397)

>> Meredith Monk: Book of Days (ECM 1399 NS)

… . …

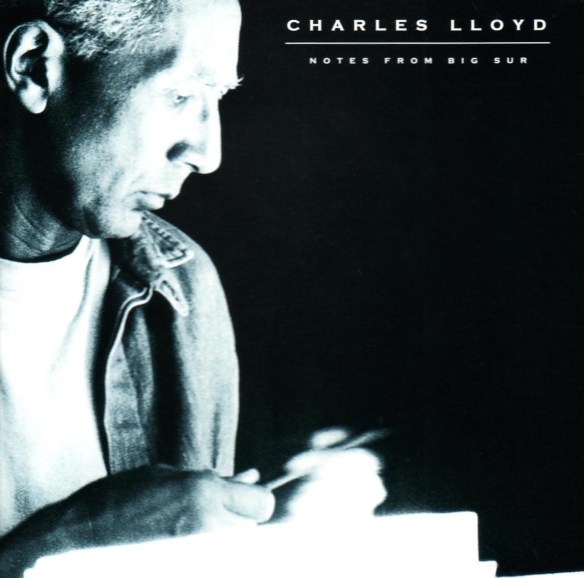

Notes From Big Sur (ECM 1465)

Charles Lloyd tenor saxophone

Bobo Stenson piano

Anders Jormin bass

Ralph Peterson drums

Recorded November 1991 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

When listening to these albums in chronological order, one’s appreciation for Lloyd’s notecraft can only increase. On Notes From Big Sur he finds himself in fine company: Bobo Stenson remains at the keys, but this time bassist Anders Jormin and drummer Ralph Peterson (in his only ECM appearance) take up a coveted rhythmic role. The feeling of afterlife offered in the opener, “Requiem,” is immeasurable. Arcing into a gorgeous cradle of sound, set off by Lloyd’s unerring climb into tuneful bliss, this is one of his most profound statements on record. Smooth-as-caramel pianism widens the doors into a vista of reflection, even as Lloyd pins a tail to this comet with a ribbon of his own. Were the band to stop here, the album would already be a masterpiece.

Gratefully they press on into the more free-flowing “Sister,” in which Lloyd takes occasional punctuations in the backing as prompts for chromatic essays. Stenson has his moments in the sun, as in his spiky solo for “Monk In Paris,” cascading runs in “Takur,” and buoyant commentary of “Sam Song.” Lloyd’s pointillism comes to the fore in the latter for a formidable rendering. Jormin, too, makes a notable statement here. “When Miss Jessye Sings” (dedicated, one imagines, to Norman) is another achingly soulful track, with enough dynamics to spread over the entire album’s surface and then some. The glue that binds comes in “Pilgrimage To The Mountain.” This two-part prayer draws us into the session’s core intentions. Peterson has just the right touch in both. He traces that same mountain with footprints, leaving Lloyd to paint a sunset, and us to reckon with the secrets of its pyramidal shadow.

<< David Darling: Cello (ECM 1464)

>> Krakatau: Volition (ECM 1466)

… . …

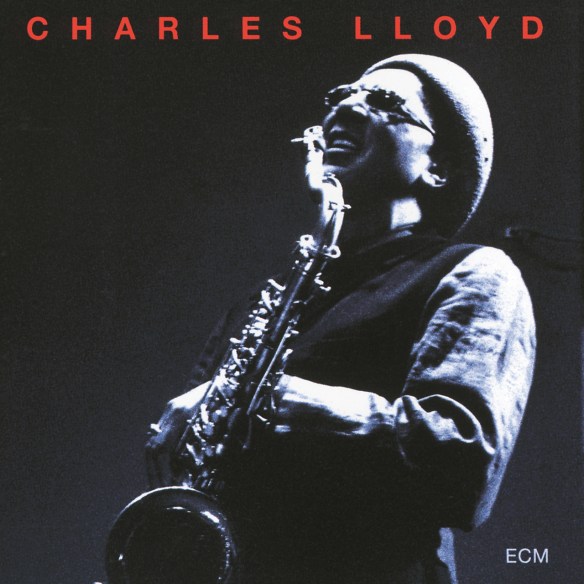

The Call (ECM 1522; also included as part of ECM’s Touchstones series)

Charles Lloyd tenor saxophone

Bobo Stenson piano

Anders Jormin bass

Billy Hart drums

Recorded July 1993 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

With The Call, Lloyd hit his ECM stride. Having pianist Bobo Stenson, bassist Anders Jormin, and drummer Billy Hart didn’t hurt. “It’s a full-service orchestra of love,” Lloyd once said in reference to this lineup. I decline to come up with a more fitting slogan, for the tender ode of “Nocturne” that opens this set of nine originals is bursting with it—that love which bears the weight of dreams on its shoulders and sews itself into the quilt of history. Stenson rings true, here and throughout, blending us into “Song” with a mélange of pointillism and legato undercurrents as Jormin’s buoyant solo carries us deeper into this moonlit cave. That Lloyd only joins in three quarters of the way through a nearly 13-minute odyssey reveals but one facet of his humility. His expression uncurls like the fist of a pacifist in “Dwija” while holding in its relief the possibility of defense. “Glimpse” has its own story to tell, painting a lakeside soiree under hanging lights, each wrapped in fragile paper and lending purpose to a slow dance one wishes might never end. Such bittersweet softness is the album’s emotional eigentone, fashioning a double-edged sword between the urgency of “Imke” and the blissful “Amarma,” the thoughtfulness of which shows Lloyd at his barest. Our leader is also irresistible in the celebratory “Figure In Blue, Memories Of Duke” (note also Stenson’s complementary touches) and the audio kiss of “The Blessing,” but saves the best for last with “Brother On The Rooftop,” an ululating duet with drums that might very well have planted the seed for his duo album with Billy Higgins, Which Way is East.

Lloyd knows not only how to tell a story, as any great jazz musician should, but also binds it in soft leather and tools it into a one-of-a-kind symmetry. He needn’t even inscribe it, for his spirit is in the details. Never one afraid to think out loud, he lets us in on everything.

<< Demenga/Demenga: 12 Hommages A Paul Sacher (ECM 1520/21 NS)

>> Federico Mompou: Música Callada (ECM 1523 NS)

… . …

All My Relations (ECM 1557)

Charles Lloyd saxophone, flute, chinese oboe

Bobo Stenson piano

Anders Jormin double-bass

Billy Hart drums

Recorded July 1994 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

Lloyd was positively soaring by the 1990s, during which time ECM’s microphones were there to catch every glorious note before it disappeared beyond the clodus. The Coltrane comparisons so often made in regard to his playing are more than justified on this especially bright, sometimes boppish, session, which like its cover speaks in bold contrasts of red, white, and gray. Lloyd blasts his colorful invention in cuts like “Piercing The Veil,” “Evanstide, Where Lotus Bloom,” and the anthemic title track with the conviction of a prophet, finding himself bonded along the way by superb kinship. Jormin always manages to find room where there seems to be none, painting his lines as he does into an intimate canvas, as if by the tip of Dali’s moustache, thereby rendering the darkened waters into which Lloyd prefers to deploy his vessels. Stenson is equally present. His gorgeous spate of calypso magic in “Thelonious Theonlyus” and luscious soloing in “Cape To Cairo Suite (Hommage To Mandela)” are the water to Lloyd’s arid valley. In both Lloyd shoulders stories of unerring ingenuity, stringing chants of hope on their way toward rapture. This leaves only Hart, who brings a ceremonial edge to the proceedings. In those two tracks for which Lloyd swaps his brass for flute (“Little Peace”) and Chinese oboe (“Milarepa”), Hart flickers, a tranquil flame of justice, spreading decks of cards to reveal an unpretentious flush, luring shadows and breathing energy into a gunmetal sky. So does this quartet begin on earth and end in heaven.

Even more powerful than the execution is the content: themes and interpretations spun from a well-pollinated mind. And so, it is Lloyd to whom we return. He catches every tiger by the tail, playing with a willingness to look beyond his licks and into the sun that grows them. From the way his sound circles the center, one can feel his horn swaying, loving, speaking. All My Relations is a celebration not only of roots, but also of the branches and leaves that would be nothing without them. This is what mastery feels like.

<< Michael Mantler: Cerco Un Paese Innocente (ECM 1556)

>> Jack DeJohnette: Dancing With Nature Spirits (ECM 1558)

… . …

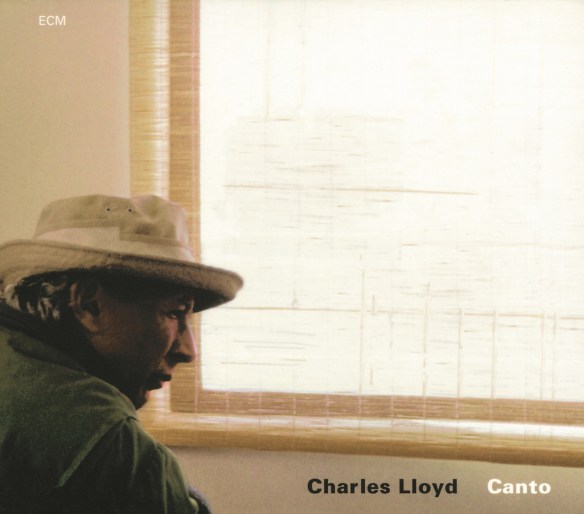

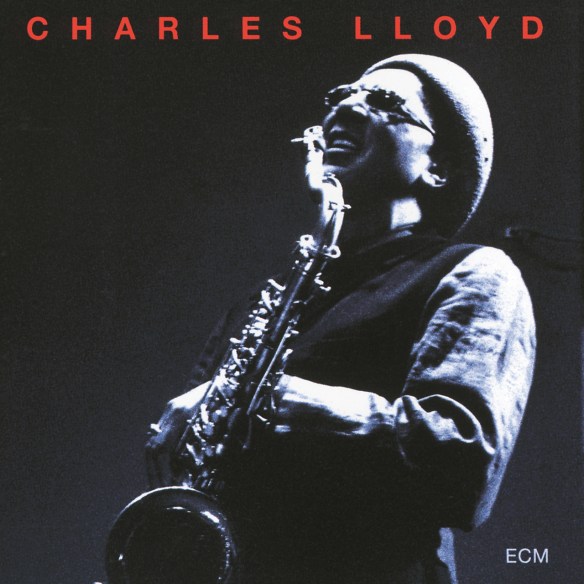

Canto (ECM 1635)

Charles Lloyd tenor saxophone, Tibetan Oboe

Bobo Stenson piano

Anders Jormin double-bass

Billy Hart drums

Recorded December 1996 at Rainbow Studio, Oslo

Engineer: Jan Erik Kongshaug

Produced by Manfred Eicher

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but the cover photo of Charles Lloyd’s Canto shows a man who takes comfort in one: solitude. In that lingering, outward gaze into the light we see the immensity of his art more clearly than any number of words might ever hope to achieve. Which makes all the more incredible his acclimation to the talents of Stenson, Jormin, Billy Hart, with whom he again shares a bond (and a studio) for his fifth ECM outing. As if any proof were needed, Lloyd confirms that he has yet to fully chart the shadows cast some seven years earlier on Fish Out Of Water. If we have Eicher to thank for rescuing his music from the obscure corner into which it had been so carelessly painted by the media, we must also acknowledge the many inspirations that make their way into this book of seven chapters.

We might as well expand the title of the opening “Tales of Rumi” to “Tales of Rumination,” for such is the nature of the ancient Sufi mystic’s presence as Stenson tickles the piano’s oft-neglected lungs. A needle of thought appears and recedes, pinholing the night’s canvas with stars, each a camera obscura of time. As the trio steps into the foreground, giving blossom to this fragrance, Lloyd filters the spotlight with his rusted tenor, peaking above clouds of golden tenure. He would sooner slow down this train than ride it to the last station, content as he is to linger in patient refraction. We hear this also in the chromatic disc that tiddlywinks us into “How Can I Tell You.” He rolls and bakes this and every theme into a perfectly layered filo, never afraid to favor certain notes over others. It is his way of defining a center from which all other centers grow. Each is of equal weight. If anything, the balance of fadeout and all-out burn in “Desolation Sound” emboldens us to accept that weight as if it were our own. A Satie-like descriptiveness welcomes us into the title track. Built of air and memory, it features the rhythm section’s most attuned work of the set and epitomizes the tender robustness at which Lloyd is so adept. “Nachiketa’s Lament” draws its name from a tale in the Upanishads and the selfsame boy who frees himself from saṃsāra in his rejection of material things. Lloyd finds solace for this retelling in the Tibetan oboe, in combination with drums, for a portrait of fruitless plains and empty bodies. Jormin and Stenson reveal their signatures only as the sun sets into the hills of “M,” of which the mineral-rich bass provides a solid perch for the tenorist’s heavy wing beats. Hart shakes off his fair share of stardust in a solo to remember before the grand sweep of “Durga Durga” disturbs the mandala in the immediate wake of its completion.

Listening to Lloyd, especially as part of the quartet with which this set ends, is a multisensory experience. By the filament of his restraint he spins earth-shattering hymns. Opting always for a restorative edge, Lloyd finishes his tunes like someone who never wants to. He practices what he preaches and passes through criticism like a ghost through walls.

“Do not look at my outward form, but take what is in my hand.”

–Rumi

<< Bjørnstad/Darling/Rypdal/Christensen: The Sea II (ECM 1633)

>> Tomasz Stanko Septet: Litania (ECM 1636)